In no uncertain terms, 2020 has been one of the most memorable years in our country’s history. And while this year brought challenges that many of us would rather soon forget, we can’t dismiss 2020 in Houston without acknowledging some of the galvanizing moments that both defined our region’s year and served as indicators of its future — both good and bad.

In 2020, Greater Houston was at the center of a historic call for racial justice in America; it was a potential target in a record-setting hurricane season; it broke other records in a closely watched election; it continued to evolve and develop new resources for residents, all amidst the terrifying uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before we all move on to our plans and ambitions for a (hopefully) brighter 2021, let’s take stock of what 2020 meant to Greater Houston.

How COVID-19 impacted Houston, by the numbers

For many, the year 2020 is and always will be inextricably linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. Like every city across the globe, the greater Houston region has had to contend with this deadly virus in its own ways, as myriad consequences continue to impact our region as the year draws to a close.

COVID-19’s spread in Greater Houston

Despite early signs of success in battling the spread of COVID-19, the greater Houston region emerged as a virus hotspot as the year went on. While mask wearing and social distancing efforts have helped us avoid some worst case scenarios, the virus has still taken an unmistakable toll on our region in the form of deaths, business closures, job losses, worsened mental health, evictions, and much more.

Here’s how the virus has hit our region:

Measuring COVID-19’s impact in Greater Houston

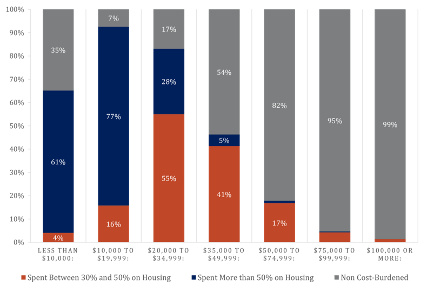

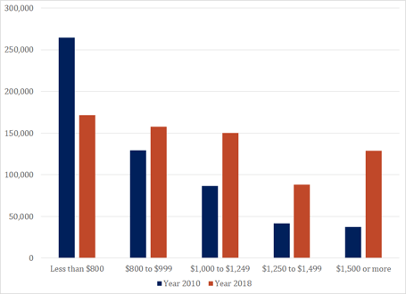

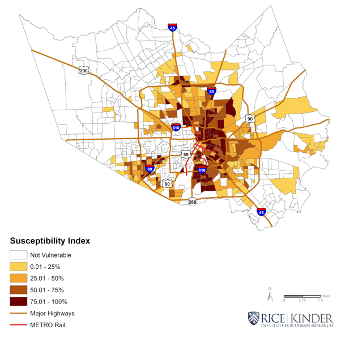

While the many effects of the pandemic will likely take years to fully make themselves known, Greater Houston has already felt severe impacts throughout the region. Between changes in consumer habits, stay-home orders, and shifts in demand, many residents in Greater Houston have lost their jobs, with those who work in restaurants,bars and construction hit hardest. After six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 45% of surveyed Harris County residents reported losing income/employment, according to the Episcopal Health Foundation. As with infections, Black and Hispanic residents in Harris County have been disproportionately impacted by job losses in the wake of COVID-19.

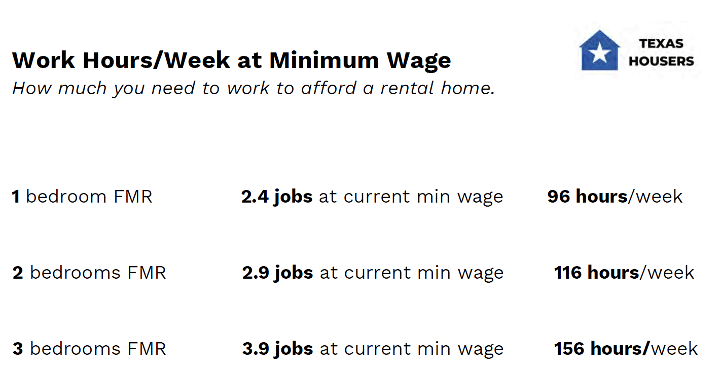

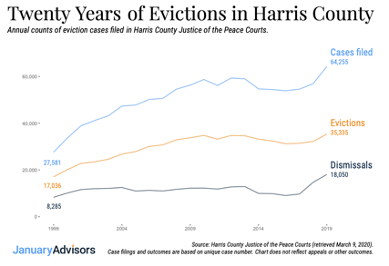

Despite eviction moratoriums enacted early in the pandemic, many Houstonians are still facing eviction. There have been 17,414 eviction filings in Houston between March 15 and December 9, according to data from Princeton University’s Eviction Lab. That places the fourth-largest city third in the nation for evictions filed during the pandemic, behind New York City and Phoenix.

Unsurprisingly, all of this has had a negative impact on residents’ mental health, young and old alike. About 44% of surveyed Harris County residents reported worse mental health six months after the pandemic began.

While multiple vaccines are currently on their way to market, the ramifications of these impacts — in addition to consequences that have yet to emerge — will likely be felt throughout our region well into 2021 and beyond.

A historic partnership to enable quick response

In the face of this public health and economic crisis, we have seen leaders, partners and individuals from all walks of life step up to assist. For the first time, Greater Houston Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Houston joined forces in March 2020 to establish the Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund, raising $17 million, to help support those in our community impacted by COVID-19 and the resulting economic conditions, with a focus on disproportionately impacted communities and vulnerable populations.

$17 million to 87 unique nonprofit partners, serving more than 240,000 people so far.

As of October, nonprofit partners reported serving more than 84,576 households and 245,339 individuals in need with access to food, emergency financial assistance for basic needs and housing, services to prevent homelessness due to evictions and foreclosures, financial and housing counseling, legal assistance, and services for the homeless to help fill public funding gaps. The data show that 87% of households served are very low-income, earning 60% of Area Median Income or less.

The renewed movement for racial justice

No social movement brought more attention to the region or inspired more activism in 2020 than the renewed calls for racial justice. Following the death of native Houstonian George Floyd, in police custody and the similarly unjust deaths of Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, people across the nation joined arms, hosted demonstrations and called for our nation to address racist policies and practices in our police and criminal justice systems. More broadly, this renewed movement inspired a broader call to action to move toward racial justice in all aspects of life to right wrongs past and present.

But it wasn’t the death of George Floyd and others alone that inspired residents to take action. Despite its reputation for diversity, the greater Houston region has many long-standing issues that contribute to racial injustice and inequality in our own communities.

The following disparities illustrate only some of the inequalities Black Houstonians have to contend with in Greater Houston:

- Income inequality: The median income for a Black household in Greater Houston is $47,376, 44% lower than the median income for white households ($85,981). Research shows that Black people are paid less even when we control for education and occupation.

- Poverty: About 20% of Black Houstonians live in poverty compared to 7% of whites.

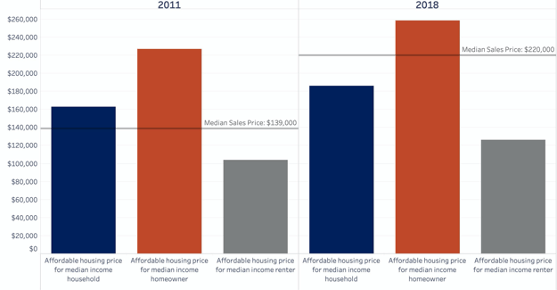

- Homeownership: At 41%, Black Houstonians own homes at lower rates than any other race/ethnicity in Houston — for comparison, 71% of white residents own homes. This disparity is due to decades of racist lending and housing policies intended to exclude Black homeownership.

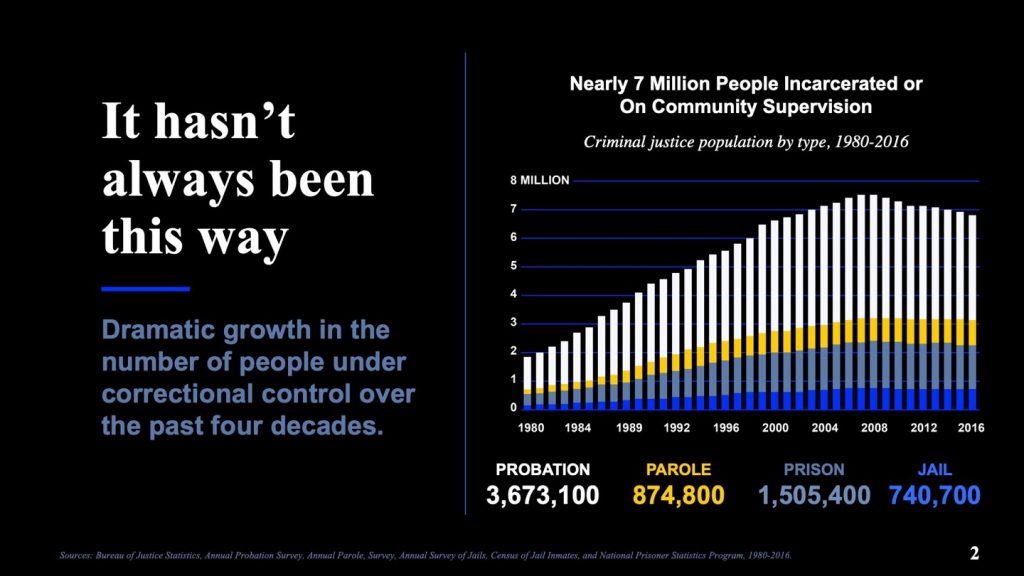

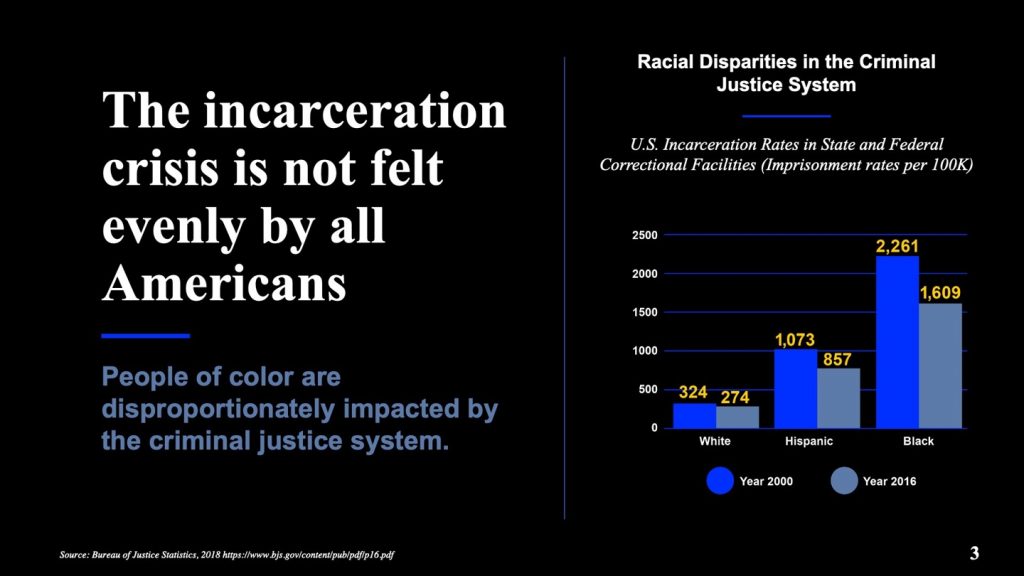

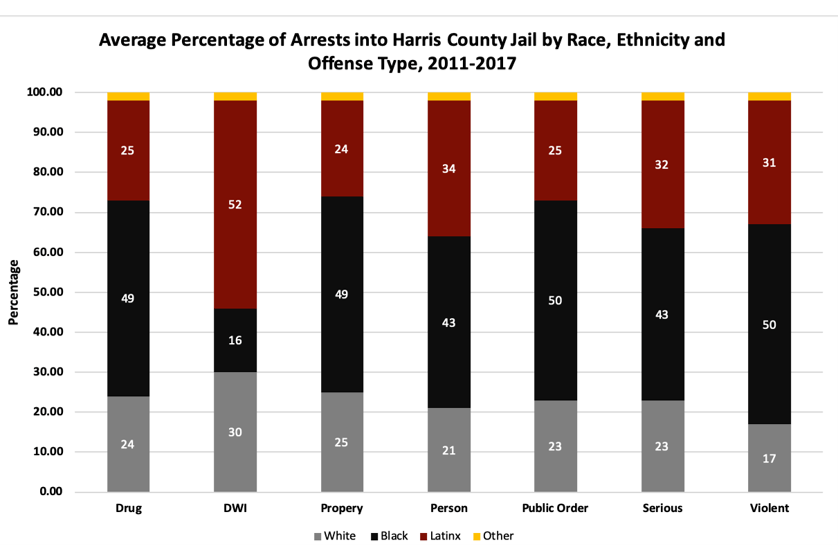

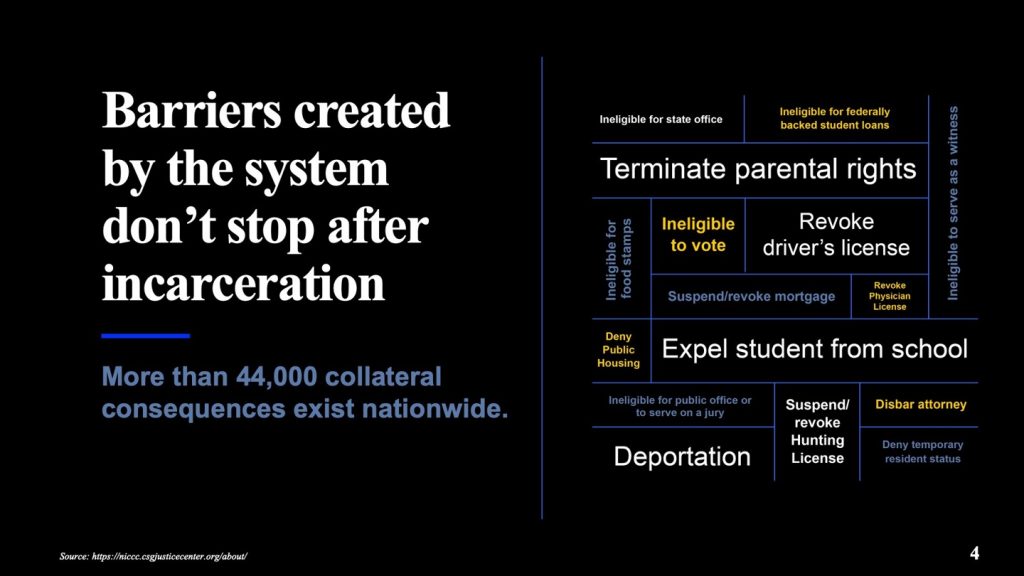

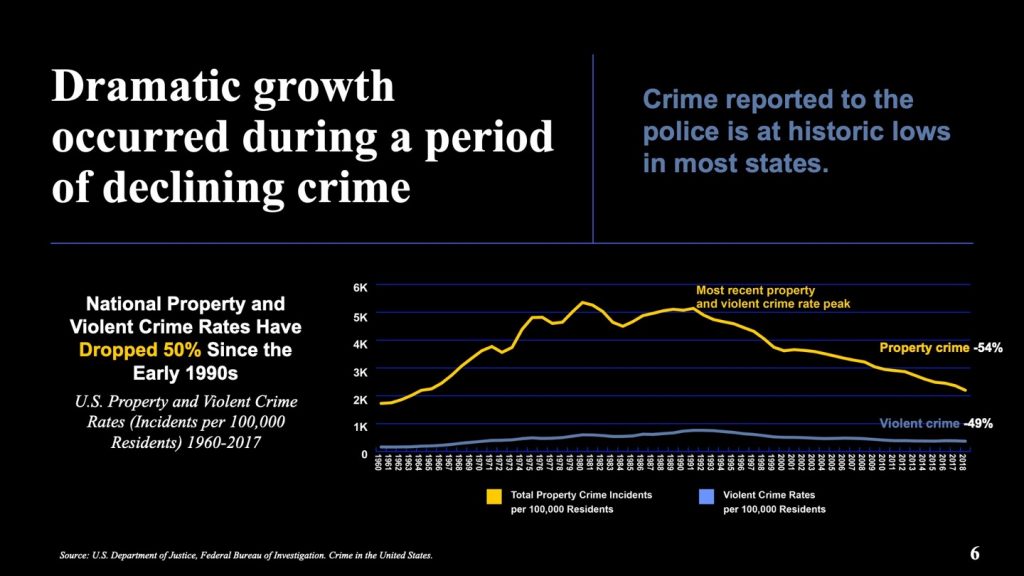

- Criminal justice: Black adults and children alike are involved at the criminal justice system at significantly higher rates than white residents. Black adults are four times as likely to be arrested in Harris County than whites and Black youth are referred to juvenile probation departments at more than two-to-three times the rate of white youth.. Black people are more likely to be associated with criminality, and as a result, their communities are over-policed. Additionally, racial bias in the system disadvantages Black people at every stage.

Inspired by these long-standing inequities and the brutal deaths by police that laid them bare this year, Houstonians took to the streets in a moment of collective awakening to speak out against the legacy of racial injustice in our communities.

60,000 people gathered in Houston to demonstrate against racial injustice.

People throughout Houston including politicians, rappers, athletes and police officers gathered in Houston’s downtown to march in honor of George Floyd and to shine a light on the lingering problems of racial inequity, garnering national media attention in the process. And while much work remains to be done, Houston has no shortage of activists, advocates and nonprofit organizations working to ensure a brighter future for Houston’s communities of color.

The need for progress doesn’t end with 2020; consider giving to a Black-led organization by visiting Greater Houston Community Foundation’s Giving Guide of Houston’s Black-led Organizations to deepen your commitment to racial justice and support in our community.

A record-breaking storm season

For many Houston-area residents, flooding and hurricanes have become an unfortunate fact of life. In the past five years alone, our region has faced six federal natural disasters, with 100-year flood events becoming a near annual occurrence. The frequency of these extreme weather events isn’t the only cause for concern — the costs they inspire can be devastating financially, environmentally and psychologically.

Unfortunately, these storms don’t seem to have been an aberration as the number of extreme precipitation days is projected to increase throughout the greater Houston area over the next few decades. And if 2020’s record-breaking hurricane season was any indication, these projections are all-too-likely to bear out in the coming years.

2020 Saw 10 named storms in the Gulf of Mexico.

Houston dodged more than a few proverbial bullets in 2020, to put it lightly. While the 2020 hurricane season was predicted to be busier than usual as early as April, many Houstonians still neglect preparations. In 2018 — just one year after Hurricane Harvey rocked our region — 72% of residents surveyed said they had not done anything to prepare for hurricane season. While it’s too early to say exactly what the 2021 storm season will bring, weathering future storms will require action, planning and awareness from residents and local leaders alike.

Making history during the 2020 election

Against a backdrop of challenge and uncertainty was one more historic event: the 2020 Presidential Election. While the pandemic presented new questions and challenges related to the safety of voting, Texans and Houstonians were not daunted. Ahead of the election, Texas shattered previous voter registration records by adding more than 1.5 million citizens to voter rolls for a total of 16.6 million registered voters. That early enthusiasm translated into record-breaking turnout, as more Harris County residents participated in early voting than voted in the entire 2016 presidential election.

1.4 million votes were cast during early voting in Harris County1

Harris County wasn’t the only place where early voter turnout exceeded total turnout in 2016. In Fort Bend County, more than 329,000 people cast their ballots prior to election day, surpassing the total number of votes cast during the 2016 election. Similarly, Montgomery County set a new early voting record with nearly 237,000 votes cast prior to election day, surpassing the total number of votes cast in 2016.

New sites to visit in Greater Houston

Believe it or not, 2020 in Houston wasn’t all about galvanizing moments. Even with so much uncertainty in the air, Houston’s region became a more vibrant place to live, work and play with three exciting new projects: The Nancy and Rich Kinder Building at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, The Houston Botanic Garden and a massive expansion of Houston favorite Discovery Green.

Let’s break them down by the numbers.

The Nancy and Rich Kinder Building

Long in the making, this new addition to the Museum of Fine Arts Houston is the culmination of more than a decade of planning and construction and features a variety of classic and contemporary art.

The details:

- The nation’s largest cultural construction project in a decade

- The result of more than 15 years of planning and construction

- 237,000 Sq. Feet of art from around the world

The Houston Botanic Garden

Houston is known for many things; nature and plant life aren’t exactly chief among them. But with the new Houston Botanic Garden, that may all change. Somewhere in between a public park, an outdoor museum and a community garden, the Botanic Garden hosts a variety of plants and vegetation, including species that have never grown in Houston before.

The details:

- Six unique zones spread across 132 acres of land

- 350 species of plants, all of which can flourish in the Houston climate.

- 2.5 miles of walking trails

- Two natural ecosystem areas, the Coastal Prairie and Stormweather Wetlands

Discovery Green Expansion

While much of Houston stays inside to aid social distancing efforts, the team at Discovery Green Conservancy is hard at work making sure Houstonians will have plenty to do in the years to come. Thanks to a $12 million upgrade, one of Houston’s favorite parks will have even more to offer visitors in the years to come.

The details:

- A brand new “house of cards” made up of 126 lighted playing cards

- A five-year public art program

- A brand new public playground

Here to help Houston understand what lies ahead

Projections and predictions aside, no one can truly say what 2021 holds for Houston. But whatever trends impact our region in the coming year, Understanding Houston is here to add data-driven insights and context to the issues that matter in our communities.

We invite you to join us for the year ahead — follow us on social media, subscribe to or share our newsletter and find out how you can get involved for the year ahead.

End Notes:

1Source: Texas Secretary of State