Why those who need the census most may also be those it threatens.

As a Latina whose family comes from the western border of Texas with Mexico, I have always felt the tug of two identities.

The calling to civic duty runs generations deep in my family, so when the 2010 census questionnaire landed in my mailbox, I was determined to be counted. However, the answers to my questionnaire were complicated by my present and historical position as a queer woman of color living in Texas.

With relative certainty, I was able to check the box next to “Yes. Mexican, Mexican Am., Chicano”, but when it came to the subsequent (required) question of “race”, I didn’t feel like I matched any of the options presented to me.

Had I had the right to legally marry, I probably would have designated my long-term, live-in partner as my “wife”, but since we were also required to include our “sex”, checking that box felt like outing ourselves to the same government that declined to legally acknowledge our partnership. So instead, we talked around our truth and settled on “roommate”.

Socially, a lot can change in ten years; and it has.

Changing dynamics and growing threats on the path to the 2020 Census

In 2011, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was repealed. In 2015, it became legal for me to marry.

Since 2017, however, even more has changed. While life for vulnerable communities has always come with its challenges, we’ve see new threats in laws, repeals of protections, bans, and acts of violence that have emboldened discrimination and incidents of hostility toward immigrants, people from historically marginalized communities, the Muslim community and other religious minorities, as well as trans and gender non-binary folks. This has, and will continue to have, a chilling effect as communities look to protect themselves and their families.

And this is just the beginning when it comes to the challenges our region faces in our efforts to count everyone in the 2020 Census. For many people, talking about your country of origin, race and/or ethnicity can be complicated.

“The way you identify may seem excluded from the census questionnaire or may feel too risky to disclose on a government form.”

And while we’ve made great strides in the LGBTQ community, characterizing or implying one’s sexuality or gender for government documents might not be possible or feel safe for everyone in our community.

Beyond this, the census faces other challenges like under-resourcing; some estimate that regional field offices have been reduced by half and that there will be 200,000 fewer census workers to knock on doors. The census can reconfigure political power, congressional districts and representation of states in the Electoral College. And with this, the risks associated with putting the questionnaire online for the first time are significant. Between online security issues and malicious campaigns designed to confuse or profit from vulnerable users, moving the census online comes with its challenges.

The growing risk of underrepresentation

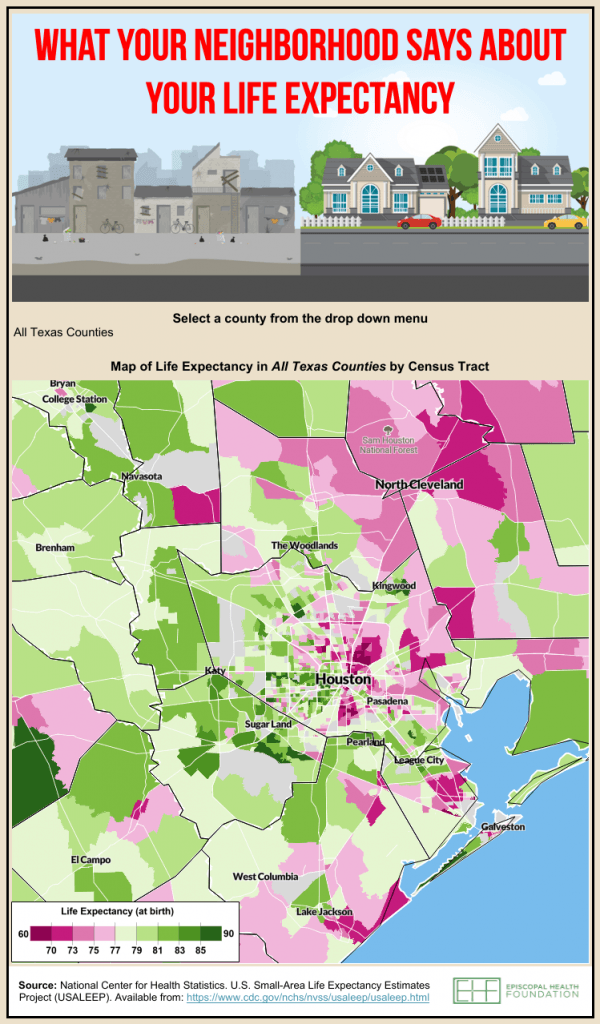

The impact of these challenges for the census itself is increased risk of undercount in our communities. In our region, the groups who have historically been undercounted are not too dissimilar from other regions. According to early research from January Advisors, these are renters, non-white communities, households with children under five years old, those in crowded housing units, people living in poverty, as well as at-risk groups like the LGBTQ community, people experiencing homelessness, religious and ethnic minorities, and residents impacted by Hurricane Harvey. However, for the Houston region, the difference is that, as the near-third largest metropolitan area in the country, these groups and risk-factors are highly represented in our community, and are in some cases, the same groups who stand to lose the most.

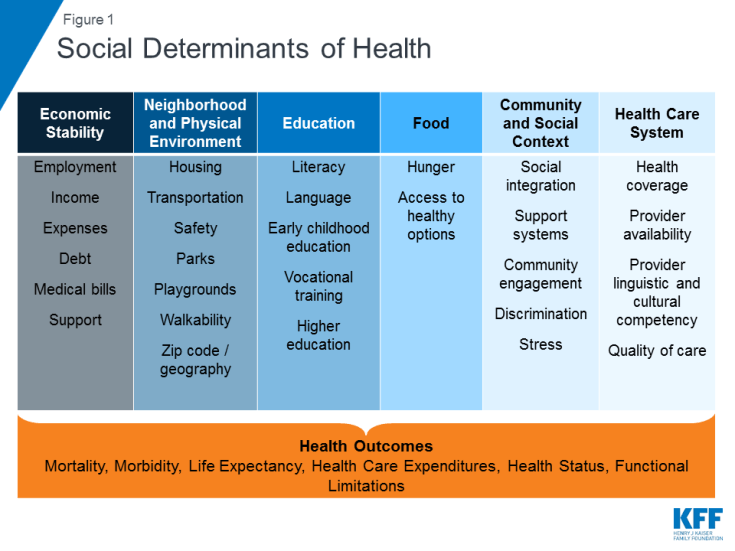

“The census affects how billions of our tax dollars will come back into our communities through federal budgeting allocations over the next decade.”

If people are undercounted in the census, we see smaller budgets for services and programs like: public transit, highway planning and construction grants; billions of dollars in community development block grants; billions in housing related dollars, including Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers and other housing assistance programs; teachers, textbooks, and other educational expenses; Title I grants that help local educational agencies serve low-income families and communities; special education grants; funds for the national school lunch program; Head Start; grants for improving teacher quality; and Community Health Centers serving low-income community members.

An important opportunity for the Houston region

Demographically, a lot can change in ten years; and it has.

Since 2010, Houston has rapidly grown and shifted at a well-documented rate. The 2020 Census is our chance to recalibrate and keep up with the demands associated with our growing population.

It is no accident that Houston in Action, with its mission to increase access and breakdown systemic barriers to civic participation, began planning for the 2020 Census during its formation in mid-2018. The members of Houston in Action reflect the multiplicity and abundance of our region’s populace and understand first-hand what’s at stake for their communities and the region at-large if we don’t all put in the hard work of counting each and every one of our friends, families and neighbors.

Houston in Action facilitates a first of its kind, regional Complete Count Committee, in partnership with the City of Houston and Harris County, engaging dozens of community groups and leaders to educate and energize our city toward a complete count.

Houston in Action members are front and center in our collective effort to reach a complete count for the 2020 Census: members like BakerRipley and the hundreds they serve at their Head Start centers; community members in the care of Hope Clinic, young people of color organizing their communities with the support of organizations like United We Dream, Mi Familia Vota, and Jolt; the Houstonians affected by Harvey and served through the housing work of groups like Avenue CDC and Texas Housers, those whose communities are represented in the work of coalitions like Empowering Communities Initiative, TFN-Texas Rising, and the Houston Area Urban League; and Houston area residents who rely on our public libraries, community centers, and public schools for education and access to the internet, to name only a few of those involved in the Houston in Action 50+ member network.

It is this on-the-ground experience that has shaped our coordination around the 2020 Census. Our work is grounded in the fundamental belief that when we create a culture of organizing ourselves for the empowerment of marginalized communities, we are better prepared to identify opportunities to engage civically, influence the systems and structures that affect our lives, and improve quality of life throughout our region.

“When we create a culture of organized empowerment, we are better prepared to influence and engage with the systems that affect our quality of life.”

The 2020 Census presents a great opportunity in this effort. For over a year, we’ve been able to build important connections, have conversations and coordinate in ways that did not previously exist. Together, we have shaped common strategies, shared resources, and built foundational systems for sharing critical impact data. We’ve developed infrastructure to grow our collective capacity and unite our efforts like never before — all necessary elements in our work to shift systems and culture, and create fair access to civic participation for residents of the Houston region.

However, we know that we can’t do this without great partners and support, and that we can’t do this overnight. While our sights are set in the near-term on the decennial census and work just ahead, we are working for true systems change for generations to come. It’s the kind of change that will be incremental — but long-lasting.

Because we know a lot can change in ten years; and it will. Together we can make it happen.

Frances Valdez is the Executive Director of Houston in Action after practicing immigration law for 13 years. Houston in Action is an initiative made up of people and organizations who have come together to advance our community forward through our respective and collective work to build a stronger Houston through a culture of civic engagement.