From protecting green spaces to fighting for gender equality and beyond, these are the women creating a better future for our region

Every March, the United Nations sets a theme for Women’s History Month, and the theme for 2021 is “Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world”. This theme celebrates the tremendous efforts by women and girls around the world in shaping a more equitable future and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, and highlights the gaps that remain.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had major impacts on the entire world, but has been particularly hard on women, who tend to be overrepresented in service industry jobs that were lost at disproportionately high rates due to stay-at-home orders. Women are exiting the workforce at higher rates than men due to historically unequal childcare between moms and dads, in addition to pre-existing gender pay gaps and overrepresentation in low-paying jobs.

For Women’s History Month, we are highlighting some of the incredible Houston-area women who are working every day to fight inequalities that have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Building a more vibrant Houston with opportunity for all, these women spend countless hours improving our community through teaching and research, creating accessible green spaces, advocating for human rights and providing resources to some of the most vulnerable in our community.

We recognize that there are many women doing incredible work in the Houston area and that this list is far from exhaustive. If you know of a leader or organization that we should highlight, please let us know!

Shellye Arnold, President and Chief Executive Officer at Memorial Park Conservancy

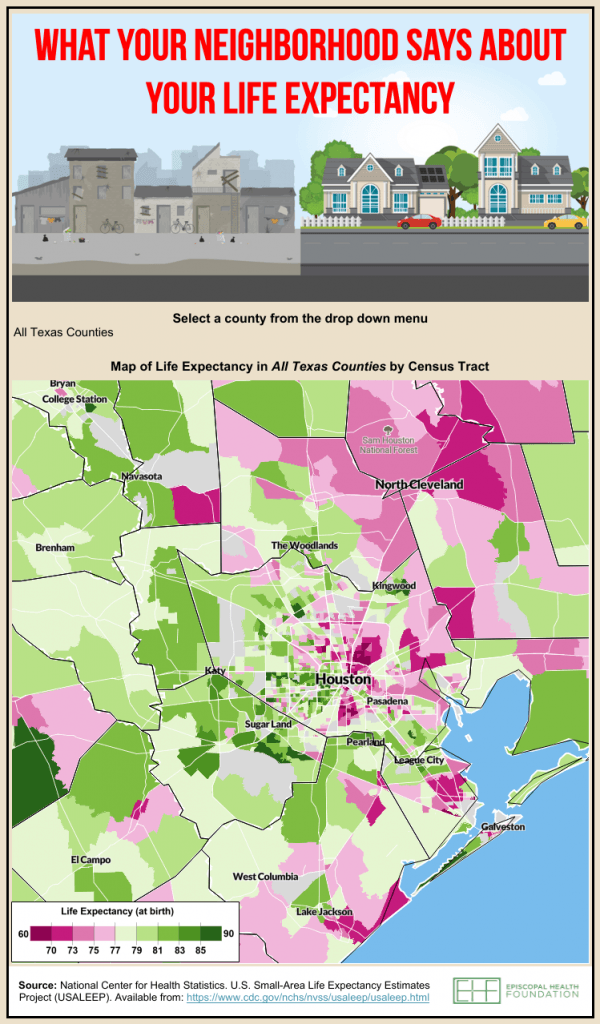

Daily, physical activity can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and even some cancers. Research has found that increases in park and recreation space are associated with increases in physical activity. The Houston three-county area boasts a number of beautiful parks, and nearly 82% of residents live within one mile of a park. However, that figure could change. Between 2001 and 2018, all three counties experienced at least an 18% increase in developed land. During the same period, these counties saw a considerable decline in the percentage of wetland, which comes with increased risk of flooding from heavy rainfall.

Shellye Arnold is working with her team to conserve our region’s green space, create a more resilient and connected Memorial Park, and improve public access to the Park. With the Conservancy’s project partners, she is leading the execution of the Park’s Master Plan – and it’s associated Ten-Year Plan – that is currently underway. She seeks to advance the Conservancy’s mission to restore, preserve, and enhance Memorial Park for all Houstonians both today and for generations to come.

“We have parks and green spaces of national significance and are continuing to grow and improve them with the public and private sectors working closely together. Innovating and investing in infrastructure for managing the storm water that regularly ravages our city is necessary. Houston has the opportunity to embrace lessons learned from cities that have tackled this problem successfully, including the creation of sustainable green infrastructure.” Shellye envisions a Houston that “will be known more as a green city, and less as a grey (concrete) city.”

Charity Carter, Founder and Executive Director at Edison Arts Foundation

Houston boasts a vibrant arts scene that is an essential part of our region’s quality of life. In fact, access to the arts has been shown to promote inclusion, community improvement, academic achievement and even improved mental health for residents. However, access to the arts in our region is not equal. Only 29% of Harris County residents who have a household income below $37,500 reported they have attended a live arts performance, compared to 58% of respondents with a household income of more than $100,000.

Charity Carter sees how interconnected the arts are with other quality of life indicators, and dreams of a Houston area where there is better quality of life for all residents that includes long term and lasting investments in communities with few resources. Through her organization,, she works tirelessly to make the arts in Houston more accessible by developing cultural and performing arts programs for children, adults and families throughout the community. Currently, they are working on a project in East Fort Bend County “that will blend arts and cultural programming, affordable housing, early literacy education, health care, entrepreneurship, jobs creation, outdoor green space and public arts into one community, creating necessary elements for an economically thriving community.”

Charity is inspired by women such as her mother, Bertha Edison, and Lauren Anderson, who was the first Black principal ballerina for a major ballet company, “because of her commitment to stay in Houston and give back to the children in Houston.” Her advice to other women is to remember that “the race isn’t given to the swift nor to the strong but to the one who endures to the end!”

Dr. Stacie Craft DeFreitas, Associate Dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at University of Houston Downtown

Quality education for all students is vital for a prosperous region and a thriving workforce and economy. However, educational attainment and success in the Houston three-county area vary significantly by race and socioeconomic status. Only 48% of economically disadvantaged students met or exceeded grade-level expectations in math compared to 71% of their non-economically disadvantaged peers, and only 14.4% of Hispanic and 26.1% of Black adults in the region hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 46.5% of white residents.

Dr. Stacie DeFreitas’ research explores what can be done to improve the academic success of youth, particularly urban, minority youth by examining mentoring relationships, faculty-student interactions and the influence of the educational environment on students. “My main concern with K12 education is the disparity across ethnic/racial groups and socioeconomic status. I have concerns that many of the public schools have been abandoned by those of higher socioeconomic status and many who identify as European American or white. This has resulted in schools that are less well funded and supported as the needs of the students are not priorities due to low rates of advocacy.”

In her career, Dr. DeFreitas felt unconfident at times and had difficulty speaking up in meetings with more senior colleagues. “I felt like I had to have everything worded perfectly and was unsure of how to take a risk.” Over time, she received mentorship and support from others, which helped her build that confidence in her knowledge and abilities. Her recommendation to other women is to “build a network of individuals to support them and that they can support. Make sure that you are giving back and not just taking. This network should be broad and cover the personal and professional arenas.”

She has been inspired by individuals such as Dr. Ernie Wade, a clinical psychologist and director of Minority Affairs at Wake Forest University, whose mentorship and impactful work inspired her to pursue clinical psychology; as well as Dr. Jennifer Montgomery, whom she describes as “a selfless person who strives to take care of others and lead a life of happiness and peace.”

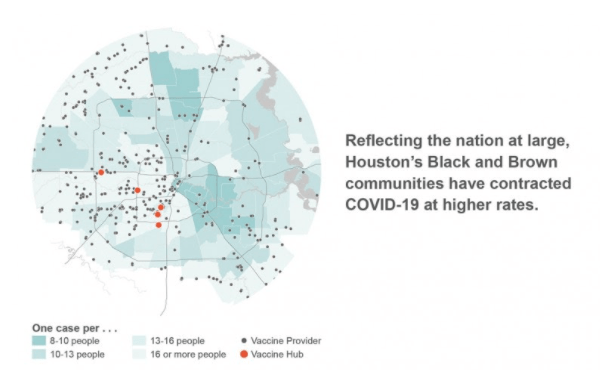

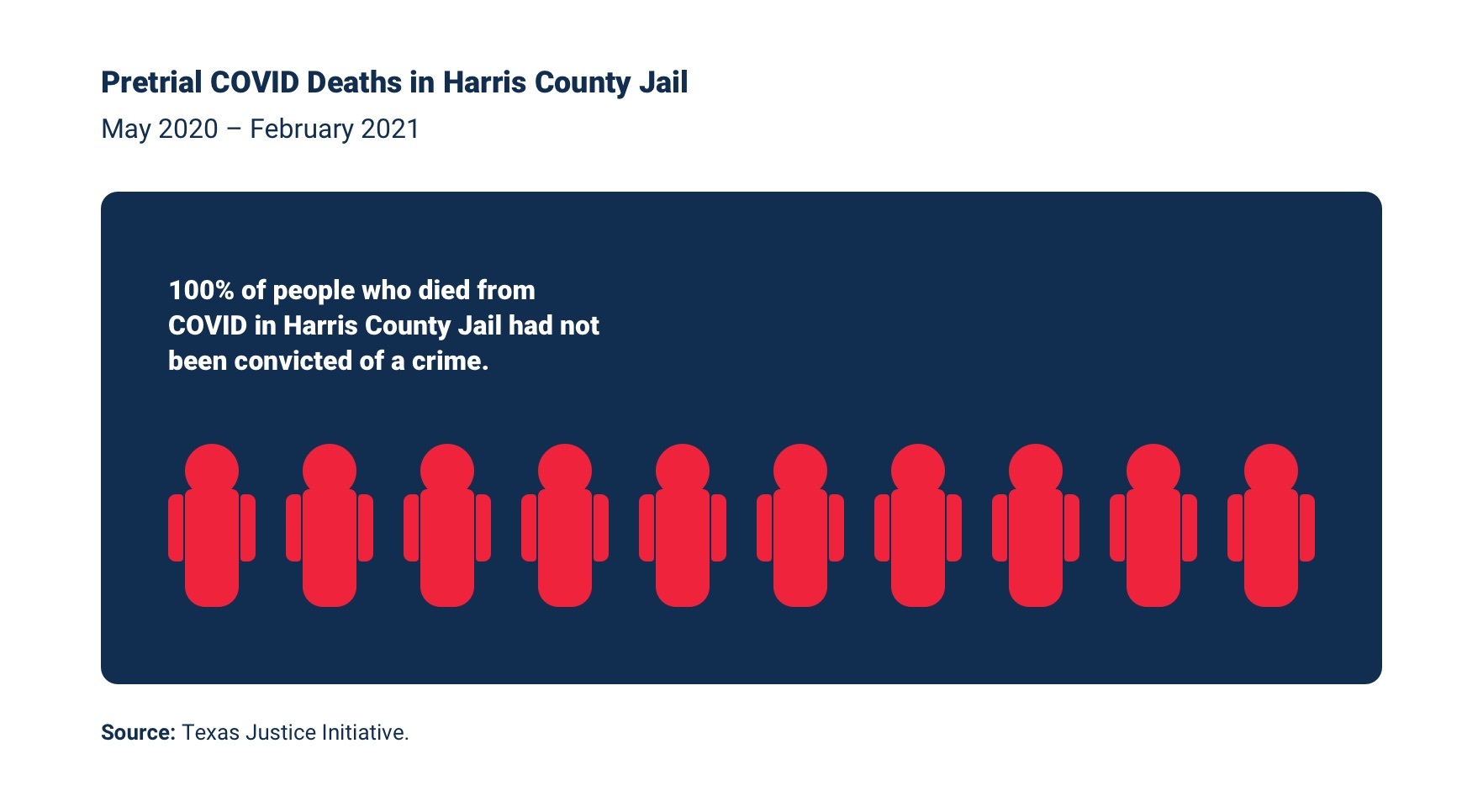

Secunda Joseph, Co-Founder of ImagiNoir/BLMHTX & Director of Community Organizing and Smart Media

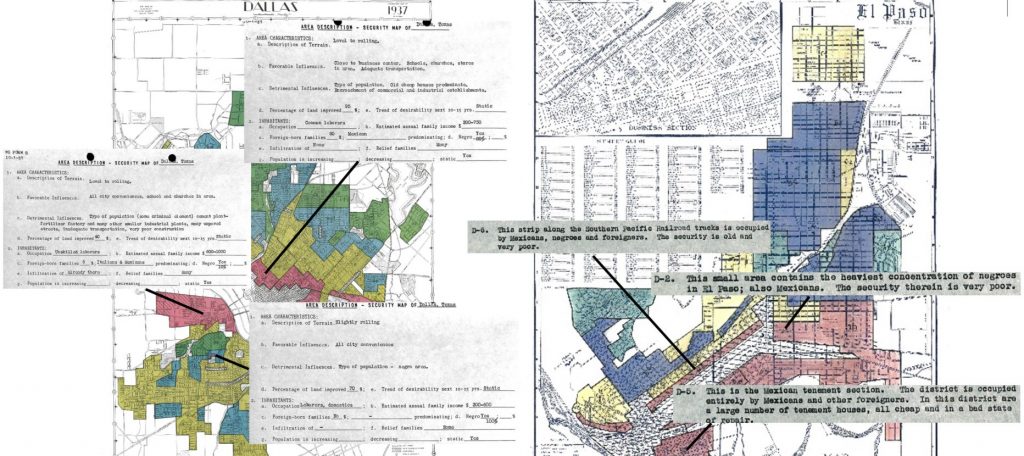

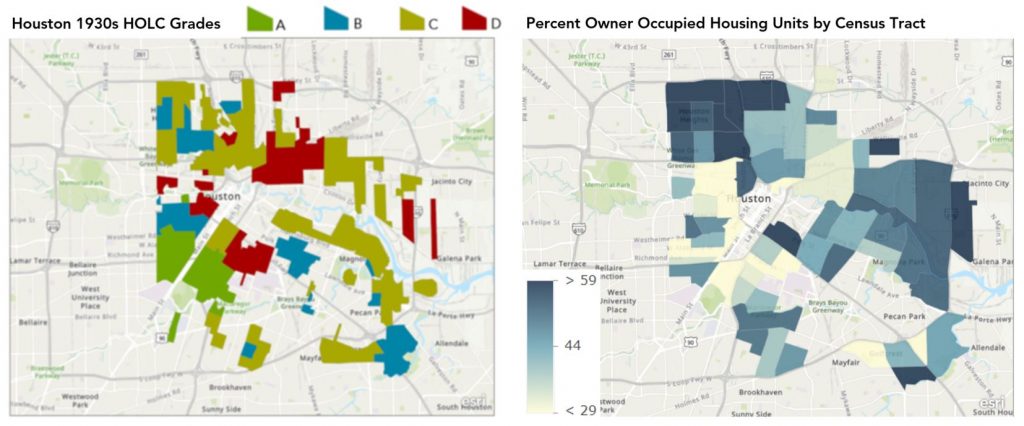

Houston leads most cities in racial, economic, and poverty disparities. It is also one of the worst for minorities when it comes to racial segregation as well as education and poverty gaps, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute. In the Houston three-county area, the median income gap between white and Black households is $38,605. That racial wealth gap will only be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the onset of the pandemic, Black Houstonians have been affected by COVID-19 at disproportionately higher rates, and Black households in the Houston metropolitan area are experiencing higher rates of income loss and more difficulties paying for usual household expenses due to COVID-19 compared to white households.

Secunda, also known as “For The People BAE” to her peers and colleagues, imagines a better Houston area in the future as a city where all community members have equitable access to resources. “I imagine a Houston where people have access, no matter where they live, to quality health care, quality education, and safety. And not safety in terms of police and punishment, but safety in terms of, I have the income I need and my neighbors have what they need. When folks have what they need crime, particularly survival crime, goes down.”

Through her organization, Secunda is coordinating and collaborating with others to effect positive change in the Greater Houston area through “trusting the people we are in the community with and using the resources that we have to highlight their voices and acknowledge the power, creativity, and wisdom that comes from these communities finding themselves needing help because of systemic oppression. Currently, that is happening through our mutual aid work.”

Secunda is inspired by many women. One women, in particular, being BLMHTX co-founder, Brandi Holmes. She admires her can-do attitude and problem solving approach to her work, as well as her perseverance to do what’s right and get the important work done even in the face of adversity and limited resources. “She inspires me because she never gives up.”

Going forward, Secunda will be working day in and day out, little by little to reimagine and recreate our current systems through an Ella Baker model of community organizing, which brings people together for sustained and coordinated strategic action for social justice.

“I would say, trust the people that we’re serving and encourage them to lead.”

Rachna Khare, Executive Director at Daya Houston

In May 2020, Houston saw a 15% increase in domestic violence offenses compared to the previous year, and a 48% increase in calls related to family violence involving aggravated assault.

Rachna Khare works with survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, her organization has seen an increase in the severity and frequency of domestic abuse, as well as the impact on clients who have recently fled an abusive relationship becoming unemployed due to the pandemic or having to cut their hours to take care of children who are at home.

“Across the county, we’re seeing women exiting the workforce. With domestic violence survivors, there is an added risk because these individuals typically experience some sort of financial control as part of their abuse. These women are exiting the workforce out of necessity which creates risks of them going back to their abusive partner due to financial need.”

Rachna is working hard to ensure these survivors have access to the resources they need to continue thriving and surviving during the pandemic. “We are meeting a moment that is so uncertain with a ton of flexibility and malleability. Meeting people where they are, not being in a box, because these challenges are not in a box.”

Going forward, Daya Houston will be focused on intentional outreach to a broader group of domestic violence survivors and reexamining the structures they have in place to be more innovative and responsive to what the community needs.

Rachna has hope in the Houston Strong commitment that she has seen from her neighbors during Hurricane Harvey, throughout this pandemic, and, most recently, in the aftermath of Winter Storm Uri where “people give philanthropically, give their time, and open their homes. I think that in a crisis we’re amazing as a city, and I would love to see that same mentality of community shifting over to the day-to-day as well.”

Anandrea Molina, Founder and Executive Director at Organización Latina de Trans en Texas

In Houston, the number of hate crime offenses rose 191% between 2017 and 2018; 75% of which were either motivated by race/ethnicity/ancestry, sexual orientation or gender/gender identity.

Ana envisions a Houston that is more accepting and inclusive. Through her organization, she supports, defends the rights of and creates survival networks for the trans latinx community.

“To create a better Houston, we need to change the systems placed here before us that we have grown to accept, and learn from our history to not repeat the same mistakes. These systems cause oppression and division within communities, and we hope to overcome all of these obstacles. Especially in the trans sector.”

In her work, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Ana has seen the disproportionate impact on transgender women who already face so many barriers. “Transwomen often feel not included in any communities and lack support systems causing a disproportion of unemployment and the situation is even worse for those who are undocumented.”

Ana is inspired by Harris County Judge Hidalgo for her strength and courage. “She fights for immigrants, the most vulnerable, and many communities have benefited from her hard work and dedication.” She also finds inspiration in the Houston immigrant community who are and always have been essential to the framework that makes Houston a robust and diverse region.

“We each have our own story and struggle we deal with. We should be proud of everything we have accomplished and survived.”*

Linda Toyota, VP Community Engagement and Development at LiftFund

Small businesses are a major driver of employment, and the entrepreneurs who run them are more beneficial to our economy and stimulate more growth than larger businesses — helping to lower poverty and improve low-income areas. The U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy report indicates that women represent 44% of the U.S. economic activity. Despite the female demographic launching the most startups, they are underfunded.

Through her leadership role at LiftFund, a nonprofit community lender, Linda Toyota not only recognizes the importance of loans to small business to create a more prosperous region, but also the impact these microloans can have “to promote wealth, business ownership, access to funding opportunities, availability of business and financial education, and information to help individuals break through the systemic barriers that have disproportionately impacted women and people from historically marginalized communities.”

Linda looks forward to a Houston area where the potential of women entrepreneurs is fully realized and where “they could impact their livelihood and the economic growth of our community. I envision a Houston that is more inclusive and equitable.”

The importance of diversity in Linda’s work and throughout her life comes from the history of her family and it aligns with LiftFund’s vision of a world where everyone has opportunity and access to education, just and equitable economies, the freedom to be fully engaged in the world, and are empowered to reach their dreams. Her parents were U.S. born Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Despite this, her father enlisted in the U.S. Army and her mother was able to leave the camp when a family sponsored her. The exclusion experienced by her parents played a substantial role in making diversity and inclusion an important pillar throughout her life. She firmly believes that “one person can make a difference.”

Elena White, Executive Director and Founder of Connective

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has declared a disaster in Fort Bend, Harris, or Montgomery counties 26 times in the past 41 years. Despite the frequency of natural disasters in the Greater Houston area, many of which involved flooding, a majority of residents do not believe the local government is successful in protecting their homes from flooding. Six months after Hurricane Harvey, about 40% of people in the three-county area rated efforts by the local government to protect homes from flooding as “poor.” However, even with assistance, the impacts of disasters can last more than several years for those with the fewest resources. About 41% of Black residents who were affected by Hurricane Harvey reported that their lives were still “somewhat” or “very” disrupted one year later, compared to 26% of white residents.

Elena White is working to improve Houston’s preparedness system in the event of a natural disaster and to ensure resources are distributed to the most vulnerable in our community when a disaster does strike.

“I believe that Houston should face the hard truths of climate change head on — leading the nation in proactive implementation of solutions to make our community more resilient, rather than facing disasters reactively.”

Through the COVID-19 pandemic recovery work and human-centered research her organization is leading, Elena has seen first-hand the disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations like single, immigrant mothers, and their stories have stuck with her.

“I think of Clara, a recently divorced mother of three, originally from Honduras, who gets her family food these days from the Food Bank and says that she often feels viewed as less than human by the staff at her apartment complex, And, Raquel, a hairstylist who lost 70% of her wages since the start of the pandemic. When asked what she’ll do if she cannot pay her rent next month, Raquel says, ‘I don’t have a plan. I don’t have a plan. The plan is day to day.’”

“My organization’s vision is to transform social services to become human-centered. I personally want to live in this city without being constantly in survival mode, and I hope to continue to push for a city where no one is constantly in survival mode.”

*Some portions of this interview were translated to English from Spanish.