The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many pre-existing disparities in access to healthcare, housing, and other life-dependent measures. These disparities often intersect with more severe outcomes in our criminal justice system, and are then met with a broken cash bail system. The outcomes dictated by these disparities can be dire. A study by the University of Texas found that of the 297 incarcerated individuals in Texas correctional facilities who died of COVID-19 between May and September 2020, 80% had not yet been convicted of a crime.1 This crisis within a crisis has further reinforced calls for pretrial justice reform in Texas and around the country.

In most of the state, pretrial justice programs are entirely dependent on cash bail, which favors wealthier defendants over poorer ones, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.2 This system not only detains non-violent offenders simply because they cannot afford bail, but also allows violent offenders the chance of release if they can afford it. This unconstitutional system transfers approximately $15 billion in the United States each year from the poorest, most vulnerable communities to privately-held bail bond corporations in the process.3

What pretrial reforms have taken place across the country?

Proponents of cash bail systems argue that releasing or offering bond assistance to pretrial offenders increases the likelihood of bail jumping, repeat offenses and crime in general.4 But a recent study conducted by researchers at Loyola University found that 2017 Cook County bail reform measures increased the number of people released pretrial without causing significant changes in the level of new criminal activity. The reforms also saved the Chicago-area community approximately $31.4 million that would have been used on bail funds in only the first six months after initiating the program. This program even included alleged felony defendants.

Data-driven insights gleaned from studies such as this have assisted lawmakers across the country in crafting evidence-based policymaking in regards to cash-based pretrial reform. On February 22, 2021, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed the Pretrial Fairness Act (HB 3653 SFA2) into law, making Illinois the first state in the U.S. to effectively eliminate cash bail. While the bill eliminates cash bail for many defendants, it still permits judges to detain individuals if they’ve been charged with felonies such as murder or domestic battery. The only misdemeanor charges that permit the use of pre-trial detention are domestic or family violence, in order to ensure the safety of the victims. In addition to reforming cash bail practices, the 764 page bill also includes provisions for the creation of a Pretrial Practices Data Oversight Board, a Domestic Violence Pretrial Practices Working Group, establishes a “civil right of action,”5 bans outright chokeholds, and even creates a confidential mental health program for law enforcement officers. While this is the most progressive pretrial justice program passed in the United States to date, even conservative thinkers find value in certain aspects of bail reform efforts such as this.

What is Harris County doing to mitigate harm caused by cash bail?

While Illinois is leading the country in progressive pretrial reforms, lawyers and policy makers in Harris County have also been working to eliminate wealth-based descrimination in pre-trial populations. In 2016, defendants in Harris County filed a class action lawsuit arguing the unconstitutionality of bail practices, resulting in the creation of the ODonnell v. Harris County Consent Decree. The resultant measures allow Class A and B misdemeanor arrestees the chance to apply for swift release or to receive bail assistance in the form of personal or general order bonds.6 Those who are not eligible for swift release or personal bonds include those arrested:

- and charged with domestic violence, violating a protective order in a domestic violence case, or making a terroristic threat against a family or household member;

- and charged with assault;

- and charged with a second or subsequent driving-under-the-influence (DUI) offence;

- and charged with a new offense while on pretrial release;

- on a warrant issued after a bond revocation or bond forfeiture7; or

- individuals arrested while on any type of community supervision for a Class A or B misdemeanor or a felony.8

Led by Brandon Garrett of Duke University, Sandra Guerra Thompson of the Criminal Justice Institute at the University of Houston Law Center, and Dr. Dottie Carmichael of the Public Policy Research Institute at Texas A&M, the Independent Monitor for the ODonnell v. Harris County Consent Decree recently released their first six-month report, showing promising signs of progress. “Gone are the days when a poor person would be locked up solely due to an inability to pay,” Garrett said in response to the findings.

Some key metrics featured in the report include a large increase in releases of misdemeanor arrestees, a large reduction in the use of cash bail in misdemeanor cases, a reduction in race disparities in the use of cash bail and an overall decline in pretrial jail days (from an average of five days or more to two days or fewer) without resulting in an increase of reoffenders. In fact, the report found a slight decline in the number of reoffenders (shown below).9

How much money is the Consent Decree saving the Harris County community?

In the Independent Monitor’s second six month report (published March 3, 2021), Dr. Carmichael and researchers at Texas A&M University found significant decreases in the cost of bail incurred by Harris County communities. In 2016, the actual cost of bonds to individuals and their families in Harris County totaled $4.4 million. Just three years later, the actual cost of bonds incurred by local communities was just over $500,000, an 89% decrease from 2016.10

89% decrease in bail spend

In the three years since enacting bail reform, annual costs to the community dropped from $4.4 million in 2016 to $500,000 in 2019.

What other improvements can be attributed to the Consent Decree?

The Consent Decree has also vastly improved the quality and administration of due process for those awaiting trial. A few key improvements detailed in the Decree are that every defendant must now receive a bail hearing within 48 hours of their arrest, defendants must be represented by a lawyer in bail hearings, forms are now translated in the defendant’s native language, and translators are available at all hearings.11 Email and phone reminders are also now in place, which helps increase the likelihood that defendants show up to trial. In a recent Understanding Houston webinar, Sybil Sybille, a Fellow at Pure Justice and member of the Community Working Group for the independent monitor of the Consent Decree, shared her thoughts regarding the efficacy of the program saying, “It’s working. People have access to bonds … as long as you haven’t violated a bond in the past.”

“An important part of the success of the Consent Decree is due to our team’s ‘Community Working Group,’” said deputy monitor Sandra Guerra Thompson. “The group is comprised of community leaders with experience in providing services for the homeless, survivors of domestic violence and sex trafficking, foster kids, immigrants and others.”12 The inclusion of independent, community-led oversight in Harris County’s recent bail reforms has set the county apart from other bail reform measures across the country, but still fails to address the population of felony defendants.

According to Dr. Howard Henderson of the Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University, pretrial justice reforms must be accompanied by programs that address the underlying “societal pre-existing conditions” that prevent fair access to mental healthcare, quality education and economic opportunity. The truth of this wisdom can be seen in the aforementioned research conducted by Loyola University in response to Cook County’s recent bail reforms. The researchers found that the most common new charge for alleged reoffenders was misdemeanor drug possession, followed by retail theft and drug dealing. The impetus of each of these offenses could be suppressed if historically neglected communities were given greater access to quality employment, mental healthcare and substance abuse counseling. Taking a glimpse at the mental health breakdown of the Harris County Jail population further supports these claims.

Has the Consent Decree improved outcomes for those with mental health indicators?

According to the continuously updated Harris County Jail dashboard, nearly three quarters of the Harris County Jail population have mental health indicators. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, mental health indicators are defined as “serious psychological distress in the 30 days prior to the interview or having a history of a mental health problem.”13

In the second six-month report created by the Independent Monitor for the Consent Decree, the data show that misdemeanor defendants with mental health problems are being arrested at roughly the same rate as prior to the Consent Decree (30% of all misdemeanor arrestees have mental health issues). However, the Independent Monitor team did find that recidivism rates in those with mental health indicators have decreased slightly in recent years, from about 45% in 2015 to about 38% in 2019. These data illustrate that while the Consent Decree has resulted in slight improvements in outcomes for those with mental health needs, additional diversion and affordable mental health care programs are needed. Local organizations such as the Harris Center for Mental Health, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities are working to fill this gap in equal access to mental health services.

Has the Consent Decree minimized the COVID risk in Harris County Jail?

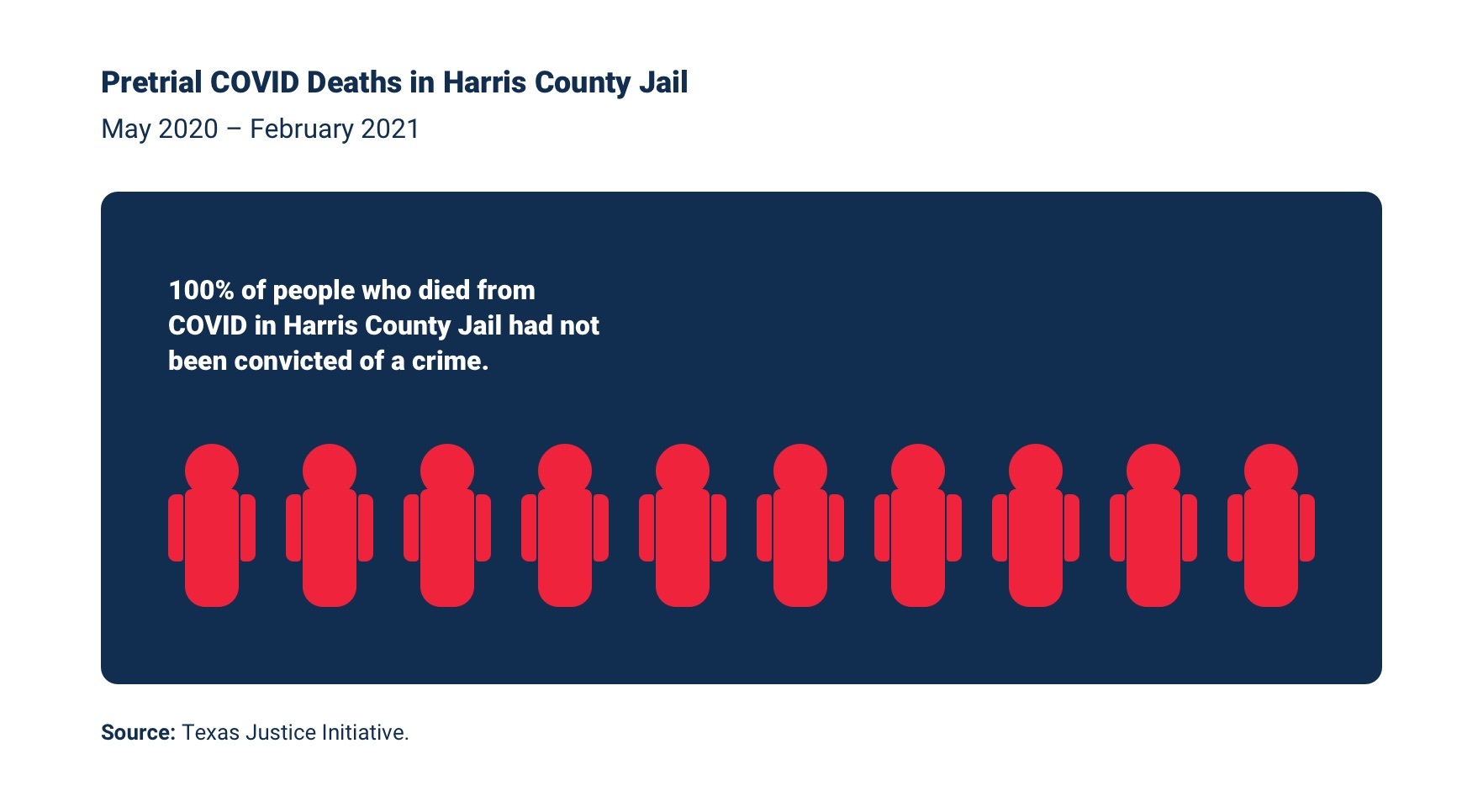

Despite Harris County’s proactive measures in enacting the Consent Decree prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large share of people who died of COVID-19 in Harris County correctional facilities had not been convicted of a crime. According to the Texas Justice Initiative’s dataset on COVID-19 fatalities in Texas correctional facilities, all ten people who died (with Custodial Death Reports14 available) from COVID-19 in Harris County Jail had been awaiting trial.

Of the ten who died while awaiting trial, five were charged with a violent crime against persons, likely making them ineligible for swift release. Two were charged with Possession of a Controlled Substance, and at least two individuals who were on staff in Harris County correctional facilities have also died from COVID-19.

While one may be quick to equate these deaths as failures of the Consent Decree, the avoidable tragedy of these deaths cannot be attributed to the program, because most of these people were not eligible for swift release under current requirements. Instead, their deaths can be attributed to the lack of a program that addresses felony defendants.

What does Harris County Jail look like now, without a pretrial diversion program that addresses felony defendants?

As of January 28, 2021, Harris County Jail was at 97% capacity, with 87% of the population awaiting trial.15 Despite efforts of local nonprofits like the collaborative leading the Community Bail Fund, Harris County Jail is reaching a breaking point. “Almost all of these individuals have bail that is set at amounts that are beyond their or their families’ financial means,” Amrutha Jindal, an attorney with Restoring Justice, stated to CBS. “As a result, they are stuck in jail – where the virus is rampant, social distancing is impossible and PPE is limited — merely due to their poverty.”

These data show that while the Consent Decree has vastly improved the efficacy of the pretrial process, the program can only do so much. As you can see in the figure below, a vast majority of those in Harris County Jail are alleged felony offenders, and therefore are not eligible for swift release or general order bonds.

This means they are forced to stay in jail for an indefinite period of time, subjecting them to life-threatening and torturous conditions, often without being convicted of a crime due to the COVID-caused delays in the courts. In an interview with the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, one incarcerated man described his experience in quarantine saying, “We had to go to the single-man cells (solitary confinement) for fifteen days, eating bologna sandwiches for lunch and dinner.” Another incarcerated person described his experience, “Sometimes, we didn’t even come out for like 30, 40 hours. We’d just be locked in the cell, the one-man cell, for like 40 hours… It’s not fair. It’s not right.”

While the Harris County Consent Decree has made great progress in reducing wealth-based discrimination and upholding due process in pretrial misdemeaner populations, additional reforms that address alleged felony offenders and the inhumane treatment that incarcerated people are being subjected to are needed. The story of Preston Chaney illustrates the urgent need for such reforms. Chaney was arrested for allegedly stealing lawn equipment and frozen meat. Despite the pettiness of these charges, burglary is a felony offense in Harris County, making him ineligible for swift release under the current Consent Decree requirements. A judge set a relatively modest $100 bail but Chaney was unable to pay. After spending three months awaiting trial in Harris County Jail, Chaney contracted COVID-19 and tragically died shortly thereafter. This entirely avoidable death was purely due to Chaney’s inability to pay bail, undoubtedly caused by “societal pre-existing conditions” alluded to by Dr. Henderson earlier.

“While the Consent Decree has vastly improved the efficacy of the pretrial process, the program can only do so much.”

What can be done to improve the pretrial process?

Although Harris County is leading Texas in amending unconstitutional bail practices, there is clearly much work to be done. Engaged citizens who would like to take part in building a fairer pretrial justice system can do so by educating themselves and/or providing material assistance to the organizations mentioned in the piece and supplied below. If you would like to stay updated on the research into the efficacy of the Consent Decree, the Independent Monitor team released their second six-month report on March 3, 2021, which provides clearer insights into the efficacy of the program. Future reports and updates can be found here. Future pretrial reforms that address alleged felony defendants may be on the horizon. According to the Civil Rights Corps, an additional lawsuit against felony cash bail practices is ongoing.

End Notes:

1Data used in this study were collected from early March 22, 2020 to October 4, 2020.

2Wydra, E.B. (October, 2017) When cash bail violates the Constitution. Constitutional Accountability Center

3ACLU (2017) Selling Off Our Freedom: How insurance corporations have taken over our bail system. Report can be found here: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/059_bail_report_2_1.pdf

4Bail jumping is the defined as the act of failing to appear to a court-mandated trial for a crime.

5A civil right of action can be defined as an individual’s legal right to sue.

6General order bonds are judicial release orders, pre-approved by Presiding Judges, that require the release of the arrestee. (Source)

7This can occur when a defendant fails to show up to court for previous offense, forfeiting their opportunity to receive bonds for future offenses.

8United States District Court For the Southern District of Texas, Houston Division. Full decree can be found here: http://www2.harriscountytx.gov/cmpdocuments/caoimages/Ex1ConsentDecree.pdf

9Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County: Second Report of the Court-Appointed Monitor (March 3, 2021)

10Garrett, B.L. , Thompson, S.G. (September 2020) Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County. Report can be found here: https://www.scribd.com/document/474748071/ODonnell-Monitor-Report-Six-Months-Final#fullscreen&from_embed

11Docket Entry No. 701-2 at 17–18, citing sections of the Texas Penal Code

12Garrett, B.L. , Thompson, S.G. (September, 2020) Monitoring Pretrial Reform in Harris County. Report can be found here: https://www.scribd.com/document/474748071/ODonnell-Monitor-Report-Six-Months-Final#fullscreen&from_embed

13Berzofsky, M., Bronson, J. (June, 2017) Indicators Of Mental Health Problems Reported By Prisoners And Jail Inmates, 2011-2012. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

14Custodial Death Reports are created for every person that dies while in custody of a Texas correctional facility. These reports include information pertaining to the individual’s cause of death, detention charges, and location.

15“The largest jail in Texas is nearing capacity. Experts warn it could become a hotbed for COVID-19.” CBS News, 2021. Accessed online.

Additional Resources

Local Organizations:

- Black Lives Matter HTX (fiscal sponsor is Project Curate)

- Center for Justice Research at Texas Southern University

- Earl Carl Institute for Legal and Social Policy, Inc.

- Eight Million Stories

- Harris County Youth Collective

- Houston Justice Coalition

- Prison Entrepreneurship Program

- Pure Justice

- reVision

- SHAPE Community Center

Regional Organizations:

- ACLU of Texas

- Restoring Justice

- Texas Advocates for Justice (program under Grassroots Leadership)

- Texas Appleseed

- Texas Civil Rights Project

- Texas Criminal Justice Coalition

- Texas CURE

- Texas Fair Defense

- Texas Inmate Families Association

- Texas Jail Project

- Texas Justice Initiative

- Texas Organizing Project

- Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Right on Crime Initiative

- Texas Voices