March 4, 2020: A Fort Bend County area man became the Houston area’s first presumptive positive case of COVID-19 after traveling on a Nile River cruise. From there, the situation worsened rapidly. Just one week later, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo was cancelled for the first time in 88 years after evidence of community spread was confirmed through a case in Montgomery County. Businesses began to close their doors and store shelves were quickly emptied as people across the region and the nation scrambled for answers. What will happen to me if I get the virus? How can I get tested? Will I keep my job? Will there be enough food? How long will this last?

One year later: we know much more than we did during those chaotic first weeks. With multiple vaccines receiving emergency use authorization, accessible testing and more treatment options, we’ve made some remarkable strides in our battle against the health effects of the pandemic. However, we also know more about the incredible toll the pandemic has taken on our region, and the impact it has had on the lives of millions of Houstonians. The data are irrefutable. Latino and Black communities have been hardest hit by the pandemic. They have paid the highest price: lost jobs, lost businesses, lost homes, lost loved ones and lost lives.

While relief may be in sight for many, the toll of COVID-19 still looms large — both for the families of people who have lost loved ones and those who have lost livelihoods. Understanding what lies ahead for our region starts with understanding where we stand today, and in a year as catastrophic as any in recent memory, it behooves us to look back and reflect on what COVID-19 has meant for Houstonians and Houston to date.

1. Nearly 465,000 Houstonians infected and 6,300 dead

Despite some early hopes that the virus would be limited in its severity and short in its duration, the grim figures one year later tell a much different tale. In the three-county area alone, nearly 465,000 people have been infected as of March 7, 2021. More than 6,300 of those infected did not survive, and residents of color and low-income communities have been hit disproportionately hard throughout the region.

As the most populous county in the region by far, Harris County has seen both the highest number of cases and the highest number of deaths in the three-county region. However, each county has had roughly the same infection rate per 100,000 residents, ranging between 7,305 out of 100,000 residents in Montgomery County to just over 7,600 out of 100,000 residents in Fort Bend and Harris counties.

Erica’s two adult brothers passed away due to COVID, only three weeks apart. As a result, Erica became the guardian for her young nephews. This has caused a great amount of stress for Erica and her husband, as they now have a family of five children to care for. When her application to the Lost Loved One Fund was accepted, she exclaimed, “Oh my God, thank you so much…you are a blessing. My family and I really appreciate it. God bless you.”

– Client story from COVID-19 Lost Loved One Fund administered by Memorial Assistance Ministries (MAM), a Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund nonprofit partner

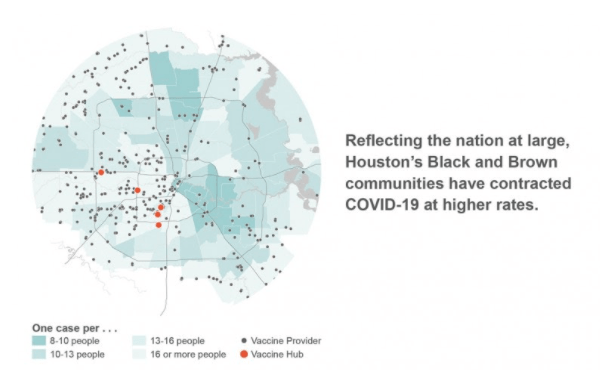

While COVID-19 may have spread through the three counties at similar rates, it has not affected everyone equally. In all three counties, Hispanic and/or Black Houston-area residents represent a higher share of COVID-19 deaths than they do the overall population.

A recent study estimated that nine family members are affected by one person who dies of the coronavirus, which means nearly 60,000 people are grieving in our region. As Dr. Julie Kaplow wrote in a recent Understanding Houston blog, “the context in which the deaths are occurring (e.g., social distancing that prevents in-person, ongoing support and collective mourning) makes the grief-related impact even more pronounced, particularly for children and adolescents.” Compounding layers of devastation is the fact that the communities experiencing the majority of infections and deaths from the novel coronavirus are the same ones who have been most affected by employment and income loss.

2. Houstonians have unequal and inequitable access to vaccines

In a year filled with difficult questions, one of the most pressing continues to be unanswered. To those who’ve spent the past year wondering when will the COVID-19 vaccine be ready? the answer is “it depends.”

According to official vaccination data tracked by the Houston Chronicle, 18% of Fort Bend County’s population has received at least one vaccine, with 12% being fully vaccinated, as of the first week in March 2021. Vaccination rates in Harris and Montgomery counties are lower in comparison, with 14% and 12% of the population vaccinated, respectively.

However, not all residents have equal access to the vaccine. The least likely to die from the pandemic are the first to become inoculated. This trend is already clear in the national data and in Texas where Hispanics/Latinos have suffered 43% of all COVID-19 cases, yet have received only 16% of vaccinations. Black Texans comprise 19% of all cases but only 7% of vaccine recipients, while Asian-American residents represent 9% of all cases but only 1% of vaccine recipients.

An analysis by the Community Design Resource Center at the University of Houston found that “vaccination sites are glaringly sparse in neighborhoods where the pandemic has been most severely felt, and instead are overwhelmingly located in the same westside neighborhoods as the rest of Houston’s resources.”

While race/ethnicity data on who has been vaccinated in Greater Houston is not publicly available, ZIP code-level data confirms that the highest vaccination rates are in communities with fewer COVID-19 cases. We can also use survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau to understand general vaccination trends by demographic characteristics — it is important to note the data presented below are not official vaccination rates.

Vaccination rate estimates correlate with income level, as residents from higher income households are more likely to have already received a vaccination against COVID-19. On the high end, 43% of residents in households earning $200,000 or more per year have received the vaccine, compared to about 17% of residents in households with annual incomes below $25,000.

3. Houstonians have lost 141,000 jobs

Rebecca is a single mom of three who found herself in a scary situation during March 2020. She contracted COVID-19 and could not go to work. As the sole provider of support for her children, the family’s livelihood depended upon her ability to work. When she was able to return to work in April, her employer had to close due to the impacts of the shutdown, leaving her unemployed and struggling to make ends meet. Rebecca received an eviction notice and had nowhere to turn. Helping her with gaining employment was essential to assisting her to get back on her feet in order to sustain herself beyond the COVID-19 funding that paid her rent. She joined our Financial Opportunity Center and enrolled in healthcare training. Rebecca now has a part time job at Texas Children’s Hospital, and will go full time earning $14/hr after gaining valuable credentials.

– Client story from Volunteers of America Texas, a Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund nonprofit partner

Between lockdown orders and massive shifts in demand, COVID-19 was a destructive force throughout the global economy, and Greater Houston was no exception to this trend. In addition to the pandemic’s well-documented effect on employment in Houston’s oil and gas industry, COVID-19 had devastating effects on construction workers, service industry professionals and arts professionals throughout the region, as unemployment skyrocketed throughout Greater Houston.

By April 2020, unemployment rates had more than tripled from their previous average, soaring to 13.0% in Fort Bend, 14.6% in Harris, and 13.2% in Montgomery counties — setting new records for the region as more than 909,800 Greater Houston residents filed for unemployment between March 7, 2020 and February 13, 2021. While the Houston region has lost 141,000 official jobs in 2020 (the countless number of workers who were employed without official record — like in domestic work — will never be known), employment is slowly bouncing back. Though unemployment rates were down to 7.5–8.3% as of January 2021, the wide-ranging economic impacts continue to disproportionately impact lower-income workers.

Those who were already vulnerable prior to the pandemic were also those hit the hardest by the pandemic’s economic fallout. According to Pulse survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau, residents in lower income households prior to the pandemic were more likely to have lost income a year later.

As of February 2021, 76% of residents who earn less than $25,000 per year had experienced a loss of income since March 13, 2020. Similarly, 60% of residents with annual earnings between $25,000 and $34,999 reported lost income. Conversely, those with higher incomes reported lost income at nearly half the rate of lower-income individuals, with 26% of those earning $150,000 to $199,999 annually and 33% of those earning $200,000 or more per year reporting lost income.

Similarly, racial trends in pandemic-related job losses largely track with existing data on poverty in the Greater Houston region. In the three-county area, 53.4–81.4% of residents living in poverty are Black or Hispanic, and residents of both groups experienced higher rates of employment income loss during the pandemic.

As of February 2021, more than half of Greater Houston residents still report employment income loss. However, Black and Hispanic residents have lost income at the highest rates. In the Houston metropolitan area, nearly two-thirds of Black and Hispanic residents have lost income since mid-March 2020 compared to 41% of white residents. And while signs of recovery are beginning to emerge, the long-term effects of these disparities will have additional ramifications for our region in the years to come. A recent study from consulting firm McKinsey estimates that it could take two years longer for women and people of color to recover jobs lost during the pandemic.

4. Hundreds of thousands of Houstonians are going hungry and worried about losing their homes

Of the many questions that arose early in the pandemic, two concerns loomed especially large: How will I be able to feed my family? and How will I be able to pay my rent? As various levels of income loss swept the region, these questions became all too urgent for many, as the financial resources needed to cover life’s basic necessities became less and less assured with each passing day.

Approximately one-third of families receiving financial assistance and groceries had never visited [our agency for help] prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

– Mission Northeast, a Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund nonprofit partner

Food insecurity in Houston during COVID-19

Throughout the pandemic, The U.S. Census Bureau has been conducting Pulse surveys to assess the needs and status of major metropolitan areas throughout the country. In 10 of the 25 Pulse surveys issued, the Houston Metro Area reported the highest levels of food insecurity of any major metropolitan area in the country.

Since mid-April 2020, about 700,000, or 15%, Greater Houston households have “often” or “sometimes” not had enough to eat. Among households with children, that rate has climbed to an average of 20%. While rates have lowered as of February 2021, complications from Winter Storm Uri could see those rates continue to increase.

There was a family that ran out of gas while in the [food distribution] line. It was a family of seven inside, (mom, dad and five children). The children were crying because they were hungry and hot. So, I went to get gas and took it to them. When they arrived for their turn in line, the mom instantly got out to get the groceries to see what she could immediately give to the children. As I watched them, I could see they must not have eaten much in days. I asked if they would like to come inside to eat more. The mom nodded her head yes and started crying. She asked her daughter to translate that it had been five days since they last ate. That they had gone to two other places in the last couple of days, but their electricity is off so they can’t cook the food. They could not pay their rent, nor electricity. Leveraging funds from GHCRF, we were able to help them with both their electric and rent.

– Client story from My Brother’s Keeper Outreach Center, a Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund nonprofit partner

Evictions and housing in Houston during COVID-19

Even in normal circumstances, housing costs are the number one expense for Houston householders. And when lost incomes and uncertain financial futures became a fact of life for half of Greater Houston residents, the consequences were swift and severe. Greater Houston quickly found itself facing an eviction crisis that persists for many to this day, despite official moratorium orders. In fact, Houston has ranked among the top three cities in the nation for evictions filed during the pandemic.

While early rent deferral programs protected some through the early days of the pandemic, the lasting effects of lost wages/employment caused many Houston residents to struggle with rent and mortgage payments as the pandemic wore on.

Houston-area renters are typically more cost-burdened than homeowners, and the pandemic was no exception. Renters’ ability to pay rent largely decreased as the pandemic wore on. In early May 2020, just under 20% of renters reported missing the previous month’s mortgage payment. But as deferment programs and unemployment benefits ran out, missed rent checks increased, as the percentage of Houston-area renters who missed the previous month’s rent spiked to 35% in early February 2021.

Amanda lost her job shortly before the pandemic and was unable to find new employment as the pandemic struck the United States. She also struggled to obtain unemployment benefits. Then Amanda’s landlord filed for eviction. By searching through the property records, a Lone Star Legal Aid attorney discovered that Amanda’s apartment complex was backed by a loan through Freddie Mac. This meant it was subject to the CARES Act, which prevented landlords from filing evictions against tenants of federally-backed properties between March 27 and July 25, 2020 during the pandemic. The lawyer requested that the landlord dismiss the case immediately. Just a few hours later, the property manager filed a Motion to Dismiss the cases against Amanda and four other tenants in Amanda’s complex.

– Client story from Lone Star Legal Aid, a Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund nonprofit partner

Homeowners faced a similar experience, with missed mortgage payments spiking to nearly 24% in late December 2020 before gradually declining back down to 18% as of February 2021. Heading into March 2021, 41% of renters reported low confidence in their ability to make next month’s payment compared to 14% of homeowners.

As with other trends related to the COVID-19 pandemic, increased difficulty paying for housing has disproportionately impacted Black and Hispanic residents, who are also more likely to be renters than white residents. As of late February 2021, 42% of Black renters said they were behind on housing payments. Without further action and assistance, the housing crisis facing Houston-area renters is likely to last well into the vaccination phase of the pandemic — and possibly beyond.

5. Learning has been disrupted for more than a million students in Houston

Just over a week after Houston’s first confirmed case of COVID-19, Houston Independent School District closed down all campuses. What began as a one week closure turned into months of at-home learning as the pandemic showed no signs of stopping, forcing educators across the state to adapt and develop online learning models fast as this unprecedented crisis took hold.

Despite valiant efforts from teachers and school districts, the impact on most students has been significant.

By the end of the 2019-2020 school year, 35% of students had gone without formal schooling due to outright cancellation of learning. As hard as teachers worked to make these programs effective, parents increasingly took on a significant share of the burden.

In the early days of remote learning, Houston-area students spent an average of 15.5 hours per week learning from members of their household, compared to just 3.7 hours per week of formal education between teachers and students. While the transition from the 2019-20 school year to the 2020-21 school year saw improvements, many students are still learning less than they would under normal circumstances.

As recently as late February, 37% of students in the Houston Metro Area reported spending less time on learning activities than they had prior to the pandemic. While most Houston-area students say they are spending as much or more time on learning activities than they did prior to the pandemic, one-third of Hispanic students — who currently represent more than half of Houston-area students — report less time spent on learning. The consequences of lost learning can be particularly pronounced for English language learners whose parents may not know or speak English at home and do not have full access to the resources needed for full online education.

For more information about COVID-19 and education in Houston, click here.

6. Three out of four Houstonians are suffering from worse mental health

Before COVID-19, Xochitl was already having a hard time providing for her family, which consisted of her partner and three children, because she was unemployed. COVID-19 has only exacerbated her financial problems. Since schools have closed she now has to balance taking care of her children, helping them with their school work, and providing them with meals — an unforeseen expense that increased her financial stress, in turn affecting her mental health. The financial assistance program has allowed Xochitl a little bit of reprieve to pay her bills.”

– Client story from BakerRipley, a Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund nonprofit partner

Between the stresses listed above and myriad others including prolonged isolation and feelings of uncertainty, COVID-19 has had a severe impact on the mental health of adults and children alike. As of late February 2021, nearly 3-in-10 Houston-area adults have reported feeling anxious or on edge for at least more than half the days of a week.

At its peak, during the week of July 21, 2020, 74% of Houston-area adults reported feeling anxious, nervous or on edge — 23% of whom reported feeling anxious every day that week. And while the most severe levels of anxiety have been in slight decline, the mental effects of the pandemic will continue to impact many in our region.

Looking back to prepare for what’s ahead

Understanding Houston has worked with experts across disciplines to keep Houston connected with the insight and data it needs to make sense of the ongoing pandemic, and that mission will outlive the virus’s spread in our community. As we look toward recovery, we’ll continue to monitor our region’s progress, sharing valuable perspectives and new data as it becomes available.

But the road to recovery is far from over. The Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund has already helped thousands of Houston-area residents attain much-needed relief, but the need has not gone away. In fact, in the aftermath of the severe winter storm the region experienced in mid-February, the need is even greater. Please consider making a donation to the Houston Harris County Winter Storm Relief Fund to help our most vulnerable communities recover as we look toward brighter days ahead.

We also invite you to follow Understanding Houston on social media and subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed and help us do what matters for all residents of Greater Houston.

*Note, all names changed to protect clients’ privacy.