Residents of the three-county region are no strangers to Houston’s heat

We all know that Houston is hot. How quickly is Houston getting hotter and why? And what — aside from making us sweat — are the implications of the region’s excessive heat?

The rising heat foreshadows many distressing possibilities as it relates to climate change, as well as less obvious public health and economic impacts. Extreme heat in particular already kills more Americans every year than any other weather-related disaster.

With eight federally declared disasters in the last decade alone, a deadly winter storm in 2021, and consecutive record-setting summers, many of us feel we are already living with extreme weather. The region is currently experiencing its most severe early summer drought conditions in nearly a decade, and Houston is coming off of the hottest June in its history. The data surrounding the rising heat and the populations most affected by it can tell us a little more about both why Houston is hot and why it matters.

How hot is “hotter,” exactly?

Members of the Houston population who have been here a while are acclimated to Houston’s summer heat as much as one can be, although the prospect of it getting hotter surely isn’t welcomed by anyone. To answer the important qualifier of how Houston is getting hotter, we look to climate normals.

Climate normals, provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (or NOAA), are 30-year averages for climate and weather variations like temperature and precipitation. Because of the 30-year period over which they are recorded, climate normals provide a more clear picture of how our weather changes than annual variances do.

The Climate Normals published by NOAA in May 2021 (with data representing 1991–2020) show that, compared to the previous 30-year average (1981–2010), average temperatures in the Houston region went up by between 0.6 to 1.0 degrees Fahrenheit, and annual rainfall increased by around two inches.

The region has already experienced a significant uptick in the number of days of extreme heat, which is defined by the CDC as days with temperatures of 95 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter. In fact, Montgomery County experienced 231 more days of extreme heat in the 2010s than it did in the previous decade — that is almost two-thirds of a year of added extreme heat over the last decade. Additionally, Harris County saw the number of days of extreme heat almost double over the same period, from 233 to 436.

Continue reading about disaster risks and climate change in Houston

Montgomery County experienced 231 more days of extreme heat in the 2010s than it did in the previous decade.

How hot could Houston’s weather get?

According to data from the Office of the Texas State Climatologist, the projected average temperature in Texas in the year 2036 is 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the 1991–2020 average, and 3.0 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the 1950–1999 average. They also project that the number of days in which temperatures reach 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the year 2036, will be nearly double the average rate for 2001–2020 in concentrated urban areas.

Long-term projections predict a story of longer summers, longer Houston heat waves and less rainfall. While, according to the Resilience Science Information Network (RESIN), average annual precipitation amounts are not projected to change significantly, the season in which the precipitation occurs is. Essentially, when it does rain, it is expected to be more intense, but there is also the possibility of longer droughts. It is important to note that although the number of hurricanes the region will face is not expected to rise, the strength of the hurricanes that do make landfall is. RESIN warns that a decline in rainfall, combined with extended summers and heatwaves, could have a serious impact on social vulnerability, critical infrastructure and natural habitats.

Projecting what Houston weather could look like in the future can be tricky, and doubt has been cast about the ability of climate models to accurately predict changes in temperature and precipitation. Research tells us, however, that climate projections tend to be pretty accurate. For example, a 2020 NASA study compared 17 climate model projections of average global temperature that were developed between 1970 and 2007 with actual changes in global temperature. Ten of the 17 models were spot on while the other seven were off by about 0.1 degree Celsius per decade. The researchers found that there was no evidence that these climate models have historically over or underestimated the impact of rising temperatures. Given today’s advanced technology and climate models, researchers express confidence that current scientists are skillfully predicting the impact of global warming.

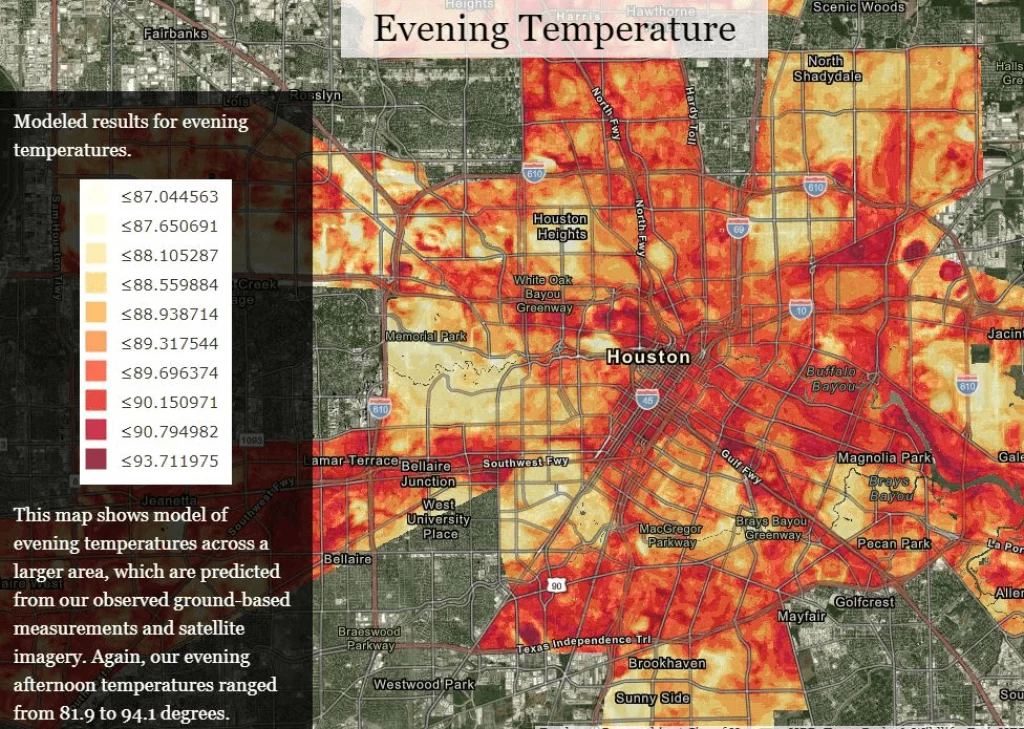

The Houston heat impacts some more than others

Houston’s heat doesn’t affect everyone equally. Temperatures often vary by neighborhoods within the same city, where built infrastructure like bridges, parking lots and buildings contribute to pockets of heat known as “heat islands.” Heat islands are most likely to occur in urban areas, where there is too much concrete and too few trees to alleviate the heat. Concrete and pavement retain heat during the day and radiates it back throughout the evening, which keeps the surrounding area hotter for longer. We can feel the difference between walking across a vast parking lot on a steamy July afternoon compared to walking down a street with trees that meet in the middle.

Houston ranks fourth in the nation in urban heat island intensity, and low-income communities and communities of color are most likely to have high nighttime temperatures in Houston.

Heat islands are the greatest driver of heat-related health issues according to Houston Harris Heat Action Team. These heat islands can result in daytime temperatures in urban areas 1–7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than temperatures in outlying areas, and nighttime temperatures 2–5 degrees higher.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), temperature extremes can worsen chronic cardiovascular, respiratory and diabetes-related conditions, and even small changes in seasonal average temperatures are associated with increases in illnesses and death. Extreme heat already kills more Americans every year than any other weather-related disaster, and WHO reports that extreme heat events are only increasing in frequency, duration and magnitude.

Extreme weather may hurt our economy

The greater Houston region has already witnessed how extreme weather can affect our local economy. In 2017, when Hurricane Harvey inundated our region over several days, nearly all businesses were forced to shut down for a period of time because it was simply impossible to get anywhere. Much of the storm’s cost, estimated at $125 billion, is attributed to interruptions in business and employee displacement.

More recently, when Winter Storm Uri surprised the region in February 2021, power outages were rampant throughout the state and burst pipes damaged thousands of businesses and homes. These impacts to the Houston economy are estimated at $130 billion.

Globally, researchers estimate that rising temperatures could reduce crop yields by 30–46% before the end of the century under the slowest (B1) climate warming scenario and 63–82% under the most rapid (A1B) scenario, which would threaten our global food supply. It isn’t just national crops and higher electricity bills; extreme weather puts incalculable stress on local communities.

In Houston, heat isn’t going away

Houstonians are already enduring the effects of excessive heat, but those risk factors will only become more acute as climate change continues to affect the region, and our region’s most vulnerable residents will bear the brunt of the harm.

How do you deal with heat in Houston? A few reminders as we get through the hottest time of the year:

- Learn to recognize heat stroke symptoms and the signs of heat-related illness.

- Check in on the elderly, the unhoused and those without access to adequate drinking water and climate control.

- Never leave people or pets in a closed car on a warm day.

- Find a cooling center!

- If you are unable to afford your cooling costs, weatherization or energy-related home repairs, contact the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) for help.

Houston is getting hotter, and we should prepare for heat and for a future of weather extremes that could repeatedly test the fabric of our region. Our continued ability to grow and prosper may depend on it.

Helpful Articles by Understanding Houston:

- Examining the Effects of Environmental Inequity in Houston

- Four Facts About Houston’s Environment That Every Resident Should Know

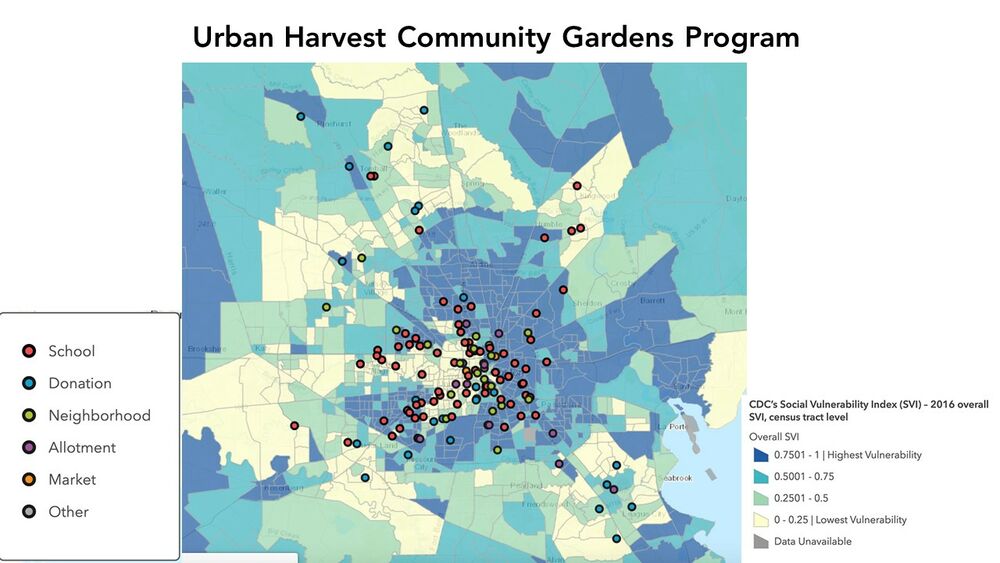

- How Community Gardens Fight Against Food Insecurity in Greater Houston

- Examining Houston’s Reputation as a Car City

- The State of Water Quality in Houston: Four Stats Every Resident Should Know