When the federal government shuts down, the effects ripple far beyond Washington, D.C.—they reach into the lives of families, seniors, and communities that rely on essential public benefits to make ends meet. Programs that provide food assistance, housing support, and healthcare become uncertain just when people need them most.

Continue reading to learn how these impacts unfold at both the local and national levels, what policy changes are shaping public benefits, and how you can help support those most affected.

11/4/25 Update: It appears that November SNAP benefits will be paid at 50%; however, we do not know how long or when those benefits will be paid since this is a federal program administered by states with different systems, processes and capacities.

What is the situation?

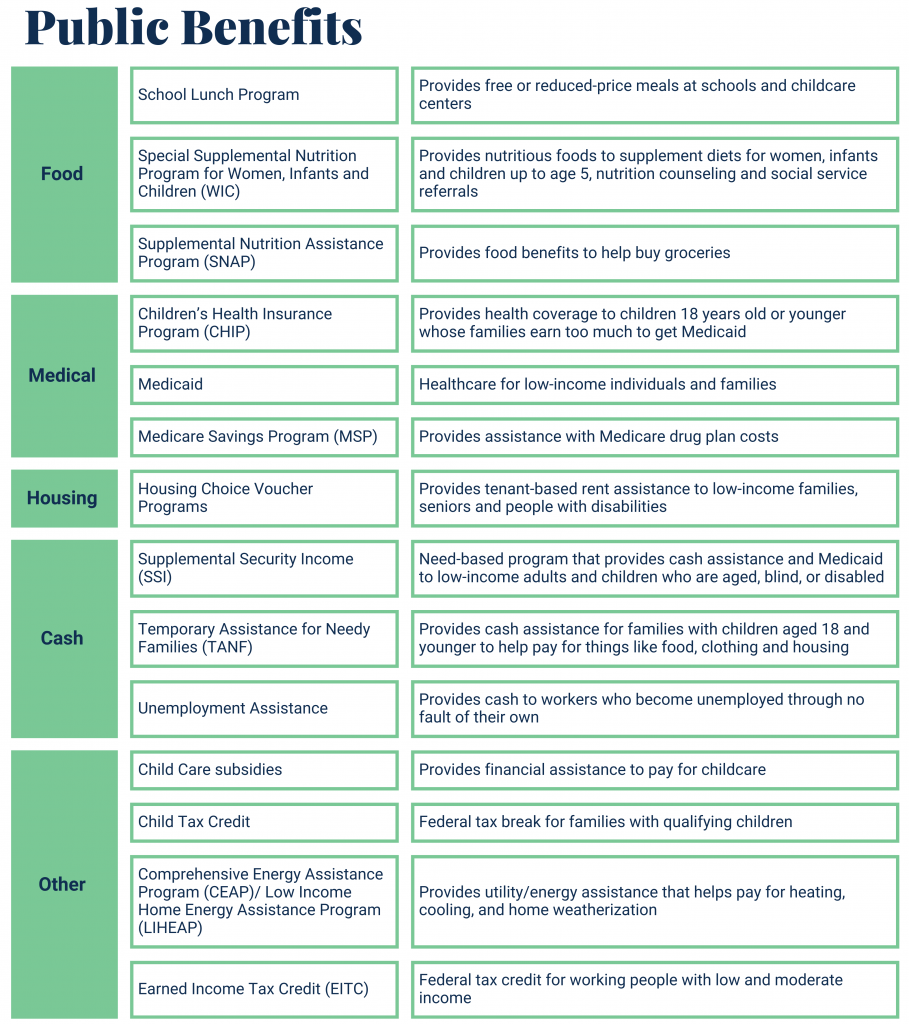

Congress is responsible for approving and passing the federal budget each year. Because a budget was not enacted by the October 1, 2025, deadline, the United States is currently experiencing a federal government shutdown—the second-longest in the nation’s history. As a result, operations for several federal programs are being affected, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides nutrition assistance to low-income families. This government shutdown means that households that utilize SNAP will not receive their benefits in November.

Who will be affected?

Nationally, 42 million Americans receive assistance from SNAP. In Texas, this will affect more than 3.5 million people. And in our three-county Houston region, about 360,000 households, or more than 770,000 people will be affected. These 360,000 households receive an average of $390 in food aid each month—a lifeline.

Among the 770,000 Houstonians who utilize SNAP, half are children under 18, with 15% (or more than 116,000) under 5 years of age. An additional 82,000 beneficiaries are older adults ages 65 and older.

Half of SNAP beneficiaries in Greater Houston are children.

Why is this a crisis?

In Texas, a family of four that is eligible for SNAP benefits earns approximately $53,000 or less per year, and an eligible single person earns roughly $25,800 or less per year. For reference, a family of four with two working adults earning the minimum wage and two children earns approximately $30,160 per year. For families earning these lower wages, SNAP benefits are not a luxury, and their sudden disruption is not an inconvenience—it is a crisis for three primary reasons:

- Food prices have increased significantly since 2020, making every dollar count

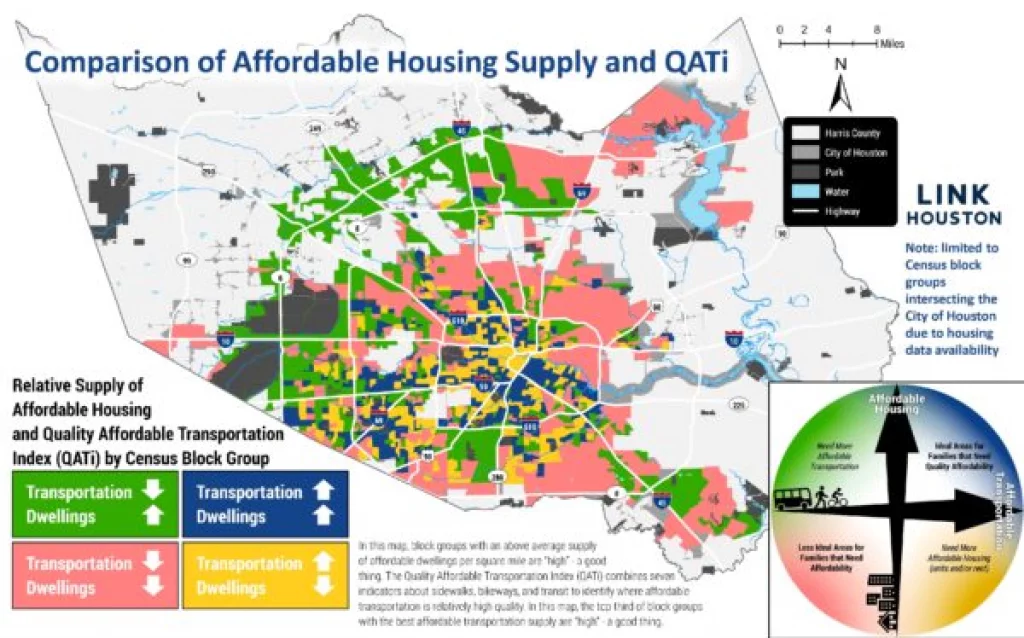

- Houstonians already experience higher levels of food insecurity than the national average

- More than half of Houston-area households are economically insecure, making food benefits a lifeline

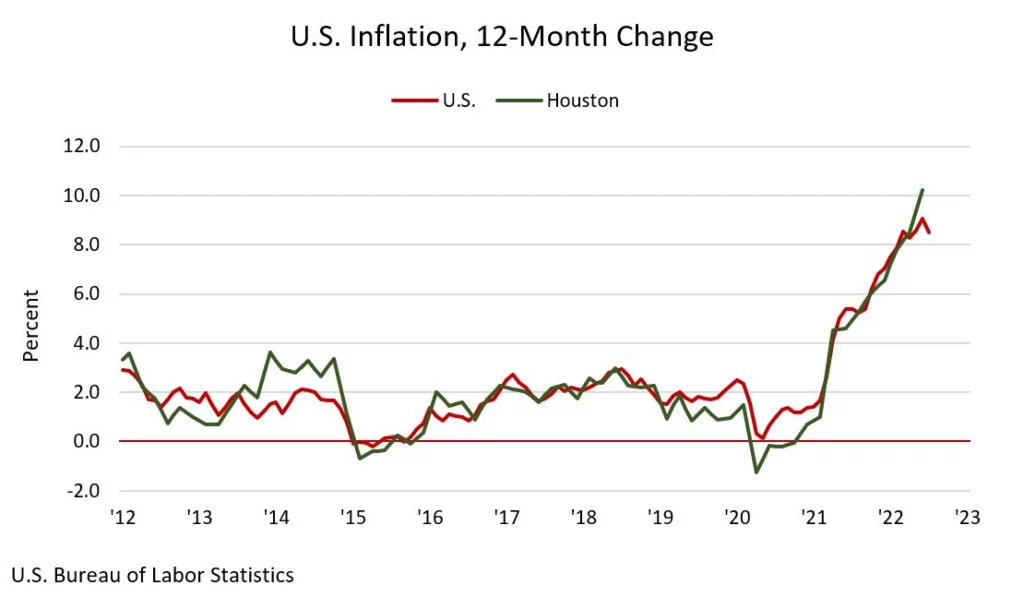

Food prices have increased 30% since 2020

A survey conducted in July 2025 by The Associated Press and NORC found the cost of groceries has become a major source of stress for just over half of all Americans—outpacing rent, health care, and student debt.

Nationally, the price of groceries has increased 29% since February 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Houstonians are already food insecure

When families struggle to make ends meet, they are often faced with difficult decisions, like which bills to pay and which to put off, or which needs are most pressing to meet. In data gathered through a 2024 survey, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research found that 39% of households in the Houston area face food insecurity, which far exceeds the national average of 14%. This insecurity is most prevalent in households that earn less than $35,000 per year, and 94% of food-insecure households reported that either they or their children went hungry.

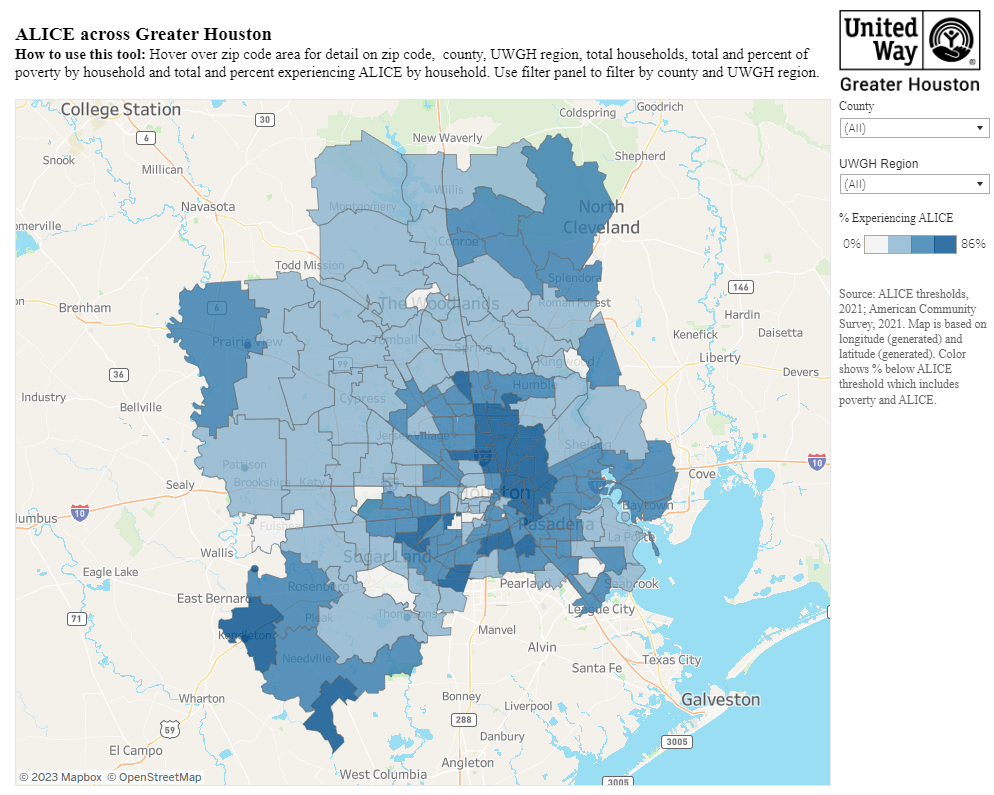

According to Feeding America, the food insecurity rate has increased substantially since 2020, reversing a downward trend from 2017 to 2019. In the U.S., children are more vulnerable to food insecurities. Harris County reports the highest food insecurity in the region, with 18% of adults and 25% of children experiencing food insecurity in 2023.

Most Houstonians lack the economic stability to weather this storm

Despite a slight decline in poverty rates over the last decade, according to new data from the United States Census Bureau, Houston is now the most impoverished major city in the nation, with one in five residents, or 21.2%, living at or below the Federal Poverty Level.

Since 2010, the poverty rate in the city of Houston has declined by only two percentage points compared to declines of 10 points in Dallas, 9 points in Austin, and 5 points in Forth Worth. In 2010, Houston ranked third highest in poverty rates among the 10 most populous cities in the nation, while Philadelphia ranked first. By 2024, Philadelphia’s poverty rate fell seven percentage points to 20% placing it second highest, while Houston took its place as the most impoverished.

Among the 10 largest cities in the nation, Houston is the only one whose poverty rate has not declined in the last decade.

In 2023, the poverty rate was 9% in Fort Bend, 16% in Harris, and 11% in Montgomery County. In Houston’s three-county region, the poverty rate is consistently lowest in Fort Bend County and highest in Harris County. Nearly 924,000 Houston-area residents lived below the poverty line in 2023.

If we look at children specifically, their poverty rates are much higher. The proportion of children under 18 living in poverty in 2023 was 10% in Fort Bend, 23% in Harris, and 15% in Montgomery County. Fort Bend and Montgomery counties have lower rates of children living in poverty compared to the state (18.4%) and the nation (16%), while Harris County has a higher rate.

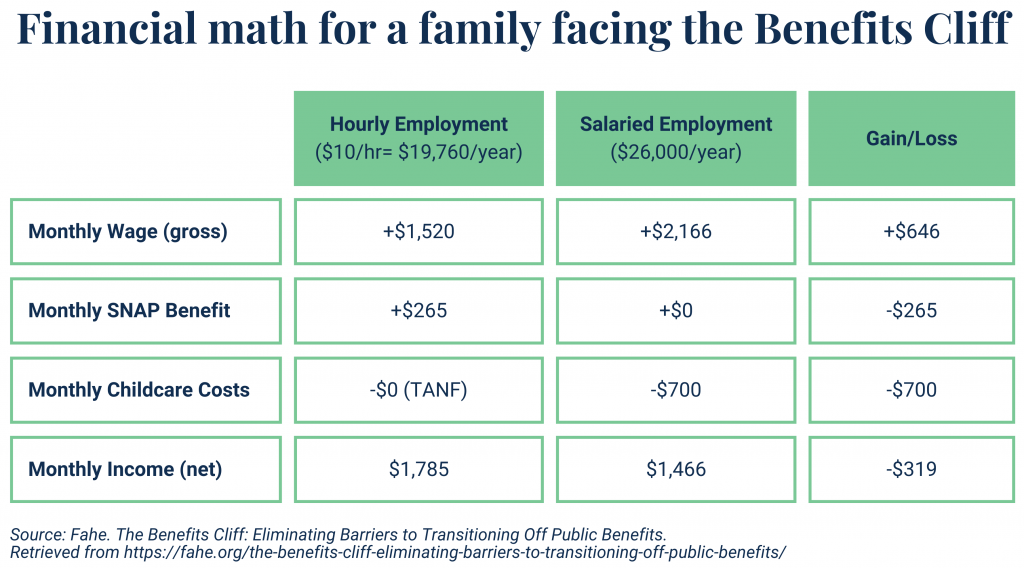

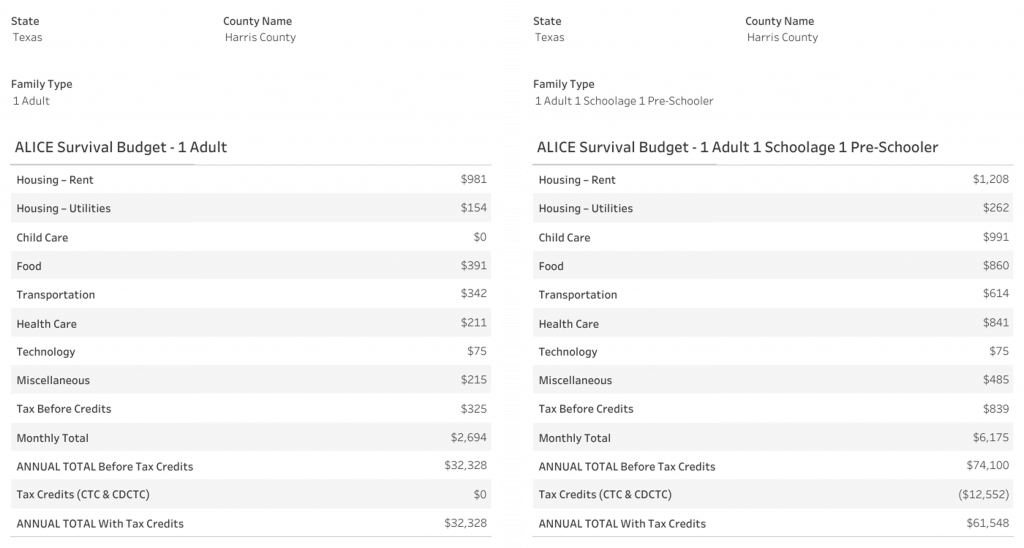

Since the Federal Poverty Level has such a low financial threshold, it is helpful to look at measures that account for the cost of living in their calculations to fully understand a region’s economic security. One such measure is ALICE, which stands for Asset Limited, Income Constrained, and Employed, and refers to families working but still struggling to meet basic needs such as housing, food, childcare, healthcare, and transportation.

To compare these two income measures, the ALICE survival budget for a family of four in Harris County is $77,792/year, compared to the Federal Poverty Level of $32,150/year for the same family.

Over one million households (44%) in Houston’s three-county region either live below the poverty threshold or experience ALICE. Nearly one in three Houston-area households was classified as ALICE in 2022, which is slightly higher than the state (29%) and national rate (29%). The proportion of households classified as ALICE was 27% in Fort Bend, 32% in Harris, and 27% in Montgomery counties.

The 44th Kinder Houston Area Survey found that 45% of Harris County residents lack the resources to cover a $400 unexpected emergency expense, signaling a significant level of financial insecurity in the Houston region. For comparison, a 2024 national study found that 37% of American adults also did not have sufficient funds to cover a $400 emergency.

How can we help? What if you need help?

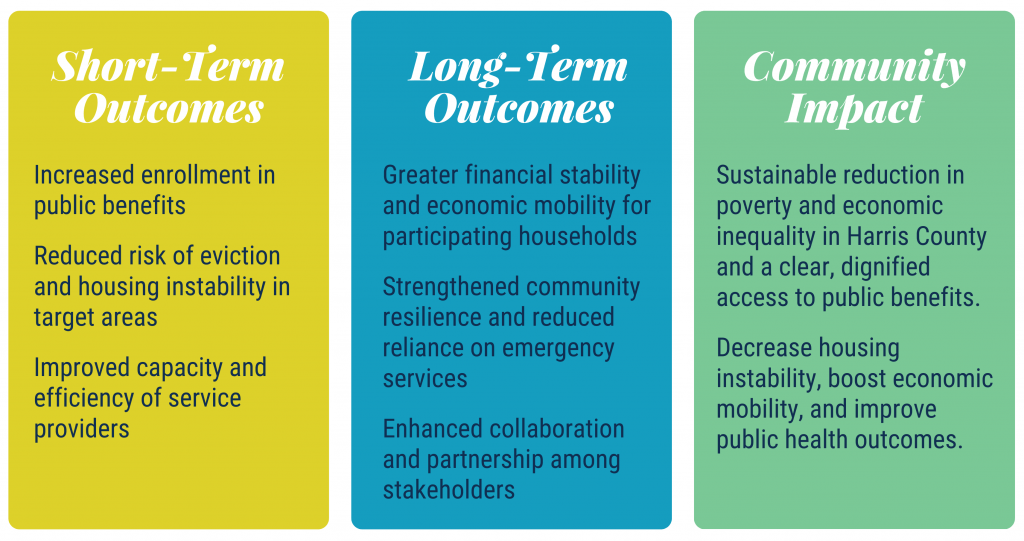

We are fortunate in the Greater Houston region to have many nonprofits that help our vulnerable neighbors every day. The Houston Food Bank is poised to support those who need access to food during these uncertain times. At a press conference on October 28, 2025, the Houston Food Bank, United Way of Greater Houston, and other community partners announced expanded food distribution efforts to provide 15,000 Houston-area families with weekly access to food assistance.

It is important to note that once the shutdown ends, most benefits should be available. See what you are eligible for using this tool.

Greater Houston Community Foundation has also compiled a list of trusted nonprofit organizations below that provide emergency financial assistance and/or basic needs assistance to those in need. Supporting these organizations now is particularly important, as early contributions help them respond quickly, scale their operations, and sustain critical services while demand is high. Gifts of any size make a difference by ensuring that vital community programs remain strong throughout times of uncertainty. Additionally, Community Foundation fundholders can utilize their donor advised funds to recommend grants that can provide direct assistance and strengthen local response efforts.

These nonprofits provide both emergency financial assistance (EFA) and basic needs services to a broad population. Counties served are noted below.

| Organization Name | County(s) Served | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Access Health | Fort Bend, Harris, Waller | https://www.myaccesshealth.org/ |

| BakerRipley | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | https://www.bakerripley.org/ |

| Catholic Charities | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | http://www.catholiccharities.org/ |

| Chinese Community Center | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | http://www.ccchouston.org/ |

| Community Assistance Center | Montgomery | http://www.cac-mctx.org/ |

| Community Family Center | Harris | http://www.communityfamilycenters.org/ |

| East Harris County Empowerment Council | Harris | https://eastharriscounty.org/ |

| Easter Seals of Greater Houston | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | http://www.eastersealshouston.org/ |

| ECHOS | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | http://www.echoshouston.org/ |

| Family Houston | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | http://www.familyhouston.org/ |

| Fifth Ward Community Development Corporation | Harris | https://www.fifthwardcrc.org/ |

| HAAM Social Services | Harris, Montgomery | https://www.haamministries.org/ |

| Hope Disaster Recovery | Harris, Montgomery, Waller | https://www.hopedrtx.org/ |

| Houston Area Urban League | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | https://www.haul.org/ |

| Interfaith of the Woodlands | Montgomery | http://www.woodlandsinterfaith.org/ |

| Jewish Family Service | Harris | http://www.alexanderjfs.org/ |

| Memorial Assistance Ministries | Harris | http://www.mamhouston.org/ |

| My Brother’s Keeper | Fort Bend, Harris | http://www.mybkoutreach.org/ |

| Neighbors in Action | Harris | https://www.neighborsinaction.com/ |

| Northeast Houston Redevelopment Council | Harris | https://www.nehoustonrc.com/ |

| Northwest Assistance Ministries | Harris, Waller | https://www.namonline.org/ |

| Salvation Army | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | https://southernusa.salvationarmy.org/houston |

| Second Mile Mission Center | Fort Bend, Harris | https://www.secondmile.org/ |

| Sewa International | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | http://www.sewausa.org/ |

| Society of St. Vincent de Paul | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | http://www.svdphouston.org/ |

| Tejano Center for Community Concerns | Harris | http://www.tejanocenter.org/ |

| Volunteers of America | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | http://www.voatx.org/ |

| Wesley Community Center | Harris | http://www.wesleyhousehouston.org/ |

| West Houston Assistance Ministries | Harris | http://www.whamministries.org/ |

| West Street Recovery | Harris | http://www.weststreetrecovery.org/ |

These nonprofits provide Emergency Financial Assistance (EFA) and/or Basic Needs Assistance to Broad or Limited Populations. Details about services provided and populations served are noted in the table below.

| Organization Name | Services(s) Provided | County(s) Served | Population | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Brothers Big Sisters Lone Star | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | Children & Youth | https://bbbstx.org/ |

| Boat People SOS – Houston | EFA | Harris | Vietnamese, Southwest & Southeast Houston | https://bpsos.org/texas |

| Boy & Girls Clubs of Greater Houston | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Waller | Children & Youth | https://www.bgcgh.org/ |

| Bread of Life, Inc. | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris | Broad | https://www.breadoflifeinc.org/ |

| Christian Community Service Center | Basic Needs | Harris | Broad | https://ccschouston.org/ |

| Coalition for the Homeless of Houston/Harris County | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | People experiencing homelessness | https://www.cfthhouston.org/ |

| Combined Arms | EFA, Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | Veterans | https://www.combinedarms.us/ |

| Evelyn Rubenstein JCC | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | Broad | https://www.erjcchouston.org/ |

| Houston reVision | Basic Needs | Harris | Youth/Young Adults | https://www.houstonrevision.org/ |

| Kids Meals, Inc. | Basic Needs | Harris, Montgomery | Children | https://kidsmealsinc.org/ |

| Living Hope Wheelchair Association | EFA, Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery | People with disabilities | http://lhwassociation.org/ |

| Precinct2gether | Basic Needs | Harris (Precinct 2) | Broad | http://www.precinct2gether.org/ |

| Precinct4Forward | Basic Needs | Harris (Precinct 4) | Broad | http://www.precinct4forward.org/ |

| San Jacinto College Foundation | EFA, Basic Needs | Harris | San Jacinto College students & employees | https://www.sanjac.edu/about/foundation/ |

| SER-Jobs for Progress | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | Broad | https://serjobs.org/ |

| Sojourn Landing | Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | Survivors of human trafficking | http://www.thelanding.org/ |

| SpringSpirit, Inc. | EFA, Basic Needs | Harris | Northern Spring Branch | http://www.springspirit.org/ |

| Target Hunger | Basic Needs | Harris | Broad | https://www.targethunger.org/ |

| The Montrose Center | EFA, Basic Needs | Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery, Waller | LGBTQIA+ Community | https://www.montrosecenter.org/ |

| The Restoration Team | Basic Needs | Harris | Broad | http://www.therestorationteam.org/ |