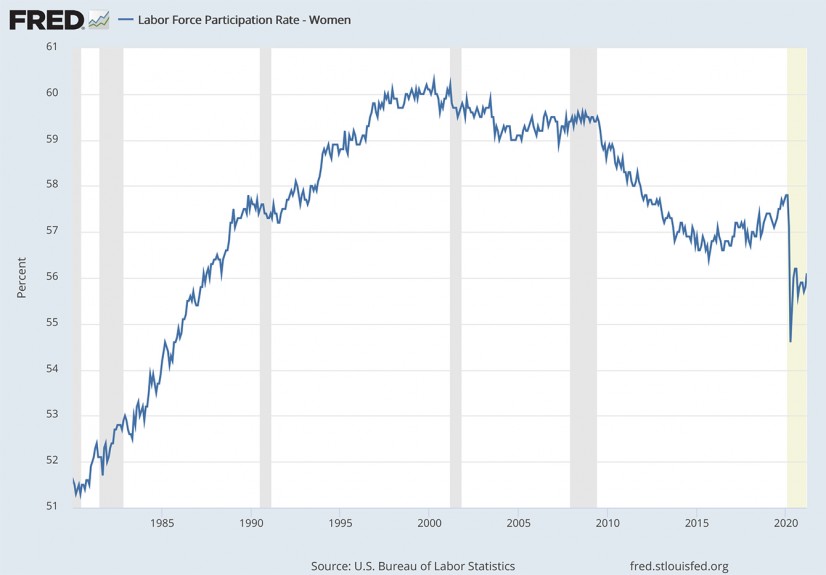

America is facing an unprecedented exodus of women from the workforce. The hard-fought gains women have made over the past 40 years are at risk of being wiped out by the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As of March 2021, more than 1.8 million women have left the workforce since the pandemic started. While this number is an improvement over the initial 4.2 million women who dropped out of the job market last April, so many women have left the labor force that the current participation rate has fallen to 56.1%, a level not seen since the late 1980s.

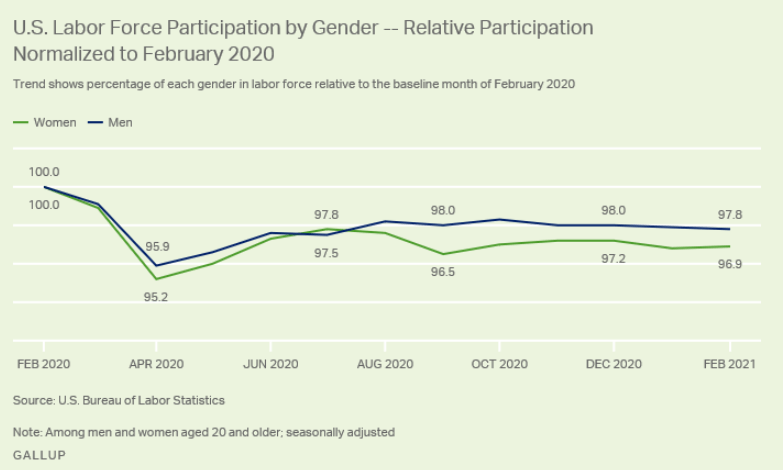

Compared to men, women initially left the workforce in disproportionately higher numbers and their return to the job market has been slower. The graph below shows that using February 2020 as a baseline for both sexes, women have lagged men in their ability to regain their pre-pandemic employment levels. This disproportionate collapse in women’s labor participation has led some to call this the first “she-session.”

Like everything related to COVID-19, the effects of the pandemic on working women varied among different groups. On average, women of color experienced greater hardships than all other workers, including white women. Comparing the experiences of Black, Hispanic and white women, Hispanic women had the highest unemployment rate — 20.1% — in April 2020, at the peak of the crisis. However, since then, Black women have found their recovery to be slower than the other groups.

20.1% unemployment

At the peak of the pandemic in April 2020, Hispanic women had the highest unemployment rate in the nation.

Working mothers of young children also have been hit especially hard. As daycares closed and school became virtual, mothers found themselves taking on an even greater share of domestic responsibilities. According to a McKinsey report, 23% of working women with kids under the age of 10 have considered leaving the workforce altogether.

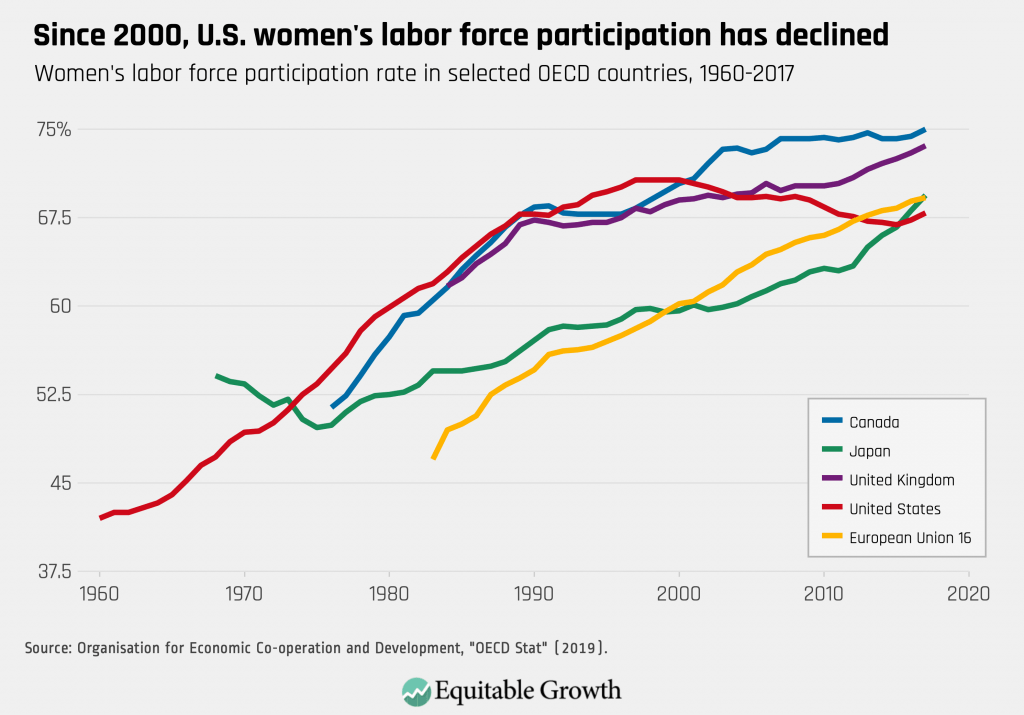

While there is some evidence that women are beginning to find their way back into the labor force, it is important to realize that, like many other disparities the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted in our society, it didn’t create this problem. It simply magnified it. The truth is that growth in women’s labor force participation has stalled since the early 2000s. It began to decline after the Great Recession, mimicking trends in men’s participation rate. Interestingly, this phenomenon isn’t replicated in other advanced economies around the world. The proportion of women in the U.S. labor force has declined since 2000 — the only country among five major OECD countries with that trend.

“23% of working women with kids under the age of 10 have considered leaving the workforce altogether.”

Societal expectations

Even before COVID-19, women performed an unequal share of the domestic responsibilities in opposite-sex-headed households, even as the amount of time men spend on housework has increased over the last 50 years. In 2018, 9.6 million females gave family and home responsibilities as their reason for not participating in the labor force, compared to just 1 million men. This is hardly surprising. When families start looking at the high costs of child care and the lower wages of women, it seems to make the most economic sense. But these individual “forgone” conclusions are predicated on structural failures.

The gender pay gap

Equal Pay Day for 2021 was March 24. This date symbolizes how much longer a woman would need to work to earn the same amount the average man did in 2020 alone. Meaning, because women earn less, on average, than men, they must work an additional 82 days to earn as much as an average man did in one year. For Black women, that symbolic day would be in August, and not until October for Hispanic women. We see these disparities at both the national and local levels. In 2017, women in Montgomery County made $20,000 less than men and women in Fort Bend County made $15,000 less. Harris County had a smaller but still significant gender pay gap of $7,500.

According to a study by the National Women’s Law Center, a woman starting her career today stands to lose $406,280 over a 40-year period compared to her male counterpart. This earning gap spans all jobs, no matter what career a woman choses. The same study found the gender wage gap in 98% of occupations. As Megan Rapinoe, the U.S. Women’s Soccer star, said in her testimony on Capitol Hill: “One cannot simply outperform inequality.” It is a truly pervasive problem, but it is hardly a new one. In fact, in 25 years, the gender pay gap has only shrunk 8 cents. At this rate, we can hope to close the gap by 2059. While this isn’t a problem exclusive to the U.S., other countries have made much better progress toward ending it.

Besides being paid less for the same work, women are also overrepresented in jobs with lower wages. While there are many underlying causes for this, one of the largest contributors is discrimination. According to a report from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, occupations with more men tend to pay better regardless of skill or education level. These trends are especially more pronounced for women of color. The implication for this being that even working full time, these women face higher rates of poverty. The negative effects extend beyond women and hurt the next generation. According to a study from the Pew Research Center, single mothers are almost twice as likely as single fathers to be living below the poverty line.

“a woman starting her career today stands to lose $406,280 over a 40-year period compared to her male counterpart”

Structural obstacles to increasing women’s workforce participation

COVID-19 has shown that, for all the advancements women have made in the workforce, the main impediment to gender equality is the structural barriers they face. COVID-19 further loosened the tenuous grip that kept many women in the workforce.

We have seen minimal gains in equal pay for equal work in the past quarter-century. The pay gap is a fundamental problem women faced before the pandemic, one they’ll continue to face throughout its duration, and even when it’s over. Research suggests that one of the most effective ways to close the pay gap is to help women achieve entry into the higher-paying, male-dominated fields, as women have an outsized representation in lower-paying jobs.

Another roadblock for many women is lack of maternity leave. Research finds that mothers offered paid maternity leave were more likely to return to work after the birth of a child both in the short- and long-term. The study found a 20 percent reduction in the number of women who left their jobs in the first year after giving birth and up to a 50 percent reduction after five years. In addition to helping women stay in the workforce, evidence suggests that paid family leave provides myriad benefits to the child, which can have a positive influence on their future.

Oftentimes for women, the problem of finding affordable child care becomes almost insurmountable. In Texas, child care often costs more than college tuition, and parents don’t have 18 years to save for it. Even before the pandemic, child care in Texas was facing a tipping point. It is estimated that U.S. businesses lose roughly $4.4 billion a year because of lost productivity due gaps in child care.

Change, while not cheap, is necessary. Significant investments that support families will help all women, mothers, fathers, and children live up to their fullest potential and thrive by improving educational outcomes, time for family bonding, and allow both women and parents to “show up” fully in their professional lives.

“In Texas, child care costs more than college tuition, and parents don’t have 18 years to save for it.”

Women are integral to our collective prosperity

Our ability to recover from the current economic crisis depends on women re-entering the workforce. Our ability to find new levels of economic growth depends on women being able to find economic success equal to men. A study often cited by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen estimates that “increasing the female participation rate to that of men would raise our gross domestic product by five percent.” McKinsey estimates that gender parity would add 19% to GDP by 2025. If we don’t want the economic fallout of COVID-19 to become permanent, we must support women and encourage their return to the workforce. Our collective prosperity depends on it.