Air and Water Quality

Air and water quality has improved over the last couple decades but remain at levels that can harm public health, particularly the most vulnerable.

Despite improvement in water and air pollution levels in Houston’s three-county region over the last two decades, People of Color and low-income communities continue to bear a disproportionate burden of an unhealthy environment.

Why air and water quality matters to Houston

Nothing is more essential to sustaining life than air and water. Houston used to be known as the nation’s smog capital in the 1990s, but the region has made significant strides since then to clean its air. However, air pollution levels caused by growing industries, heavy traffic and a car-dependent culture remain a persistent problem for the Houston region. Additionally, the Houston area has vast water resources, including a great number of major rivers and streams running across the state that support our region. These water resources support both natural ecosystems and human habitation. However, in highly-developed urban areas — particularly those accustomed to flooding like the Houston region — urban waterways take on concentrated pollution from industrial discharges, vehicles, residential and commercial wastewater, trash and polluted stormwater runoff.

Contaminated air and water poses serious health threats for residents and the environments they live in. High levels of ozone and particle population have been found to lead to premature death and other health conditions like respiratory illnesses, cancer, asthma attacks, cardiovascular damage, and developmental and reproductive damage.1 Across the U.S., about 50,000–100,000 excess deaths are attributed to air pollution.2 And contaminated water can lead to illnesses and even cause death. What’s more, our most vulnerable residents — people of color, low-income communities, young children, and older adults — tend to be disproportionately affected by environmental hazards, both in terms of higher exposure levels and more severe health outcomes.3 4

The more we know about Greater Houston’s air quality and water quality, particularly in our region’s most vulnerable communities, the better equipped we are to take informed action in order to protect these essential resources for future generations.

The data

Ozone, particle pollution and toxic waste releases contribute to poor air quality in urban areas

Though improving, high ozone levels still undermine public health in the Houston area

Ozone can be “good” or “bad” depending on where it is found in the atmosphere. Stratospheric ozone is “good” because it occurs naturally in the upper atmosphere and protects living things from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. “Bad” ozone is found at the ground level and is often called “smog.” Ozone can cause immediate breathing problems and is associated with many negative health outcomes, including asthma and even premature death.5

Ground-level ozone is not emitted directly into the air. Instead, it is formed when heat and sunlight cause chemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOC). These chemicals are produced primarily from cars and industrial processes. Since ozone is most likely to reach unhealthy levels on hot days in urban areas, typically the ozone readings reach the highest values between April and September in the region.

In December 2020 the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for ground-level ozone were set at 0.070 parts per million (ppm) averaged over an 8-hour period. This is the same standard that was set in 2015 and is lower than the 2008 standard of 0.075 ppm.

Since 2000, there has been a significant decrease in the number of days in which ozone levels were above EPA standard in our region. Harris County saw the number of days above standard fall 64%, from 70 days in 2000 to 25 in 2018. Montgomery County saw a similar decrease of 77%, from 47 days in 2000 to 11 in 2018.

While Houston has experienced long-term progress, data from recent years show a modest uptick in the number of days where ozone levels were dangerously above standard. Harris County saw the number of days above standard increase from 17 days in 2016 to 25 in 2018, while Montgomery saw an increase from 4 days in 2016 to 11 in 2018. Across the U.S., ozone levels have not decreased at the rate they were previously indicating stalling progress on improving air quality.6 Ozone levels in Greater Houston also remain high compared to the rest of the country, according to the most recent State of the Air report by the American Lung Association, which rated the ozone levels in Harris and Montgomery as an “F.”

The amount of particulate matter in Houston’s three-county region is below national standards but remains higher than national rates

Particle pollution, or particulate matter (PM), refers to small solid and liquid particles, like soot, found in the air. These particles are released into the air by different industrial processes, fires, dust, or formed from vehicle exhaust. While these particles are so microscopic they cannot be detected individually, when millions are present, they can reduce visibility and cause haze.

Particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter are referred to as PM2.5, and because of their size, they are easily inhaled by humans. In 2019, the EPA determined that both short-term and long-term exposure to PM2.5 causes early death.7 PM2.5 particles pose the greatest risk to health through cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and vulnerable populations, including children and older adults, have higher chances of being affected.

In December 2020, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decided to retain the 2012 National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM2.5 at the annual average level of 12 micrograms per cubic meter of air (µg/m3) for another five years. However, in June 2021 the EPA announced it would reexamine the standard, given the scientific evidence of the harm to people’s health. It expects to have a final rule in Spring 2023.

Does Houston have good air quality, as measured by particle pollution? In the Houston Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), the annual average concentration of PM2.5 has decreased from 13.1 µg/m3 in 2000 to 10.1 µg/m3 in 2020. This represents a 23% improvement in air quality. While this indicates progress, the reduction of air pollution in Houston has not kept up with the national trend, where PM2.5 levels fell 41% during the same time period.

As with ozone levels, there has been a leveling off of improvement in particulate matter pollution in recent years.8 This trend is also seen across the U.S and Europe and reflects the challenges to reducing PM2.5 concentrations at lower levels, even with the enforcement of long-term policies like the Clean Air Act.9

Levels of contamination in Houston-area drinking water and water bodies remain a public health concern

Clean and safe drinking water helps prevent illness, birth defects and even death.10 To ensure the water is safe for human consumption, public water systems are frequently checked to verify that the levels of contaminants present in the water do not exceed the Maximum Contaminant Levels set by the EPA. As of July 01, 2021, Texas regulates 7,053 public water systems, providing drinking water to more than 29.5 million customers.

Water violation levels threaten the safety of Houston’s drinking water

According to the Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS) federal reporting system, Harris County had a total of 1,595 drinking water violations reported from its active facilities in 2020. It had the most drinking water violations among the three counties, but it is difficult to determine the exact population impacted by each violation. Fort Bend and Montgomery counties have fewer water violations reported. Additionally, not all violations are equivalent; testing date, frequency and location can also affect the detection and severity of violations.

The majority of area water sources are bacteria-impaired

Ground and surface refer to the naturally occurring water sources beneath and above the Earth’s surface, respectively. While about 80% of the groundwater in Texas is used for agricultural purposes, mostly for irrigation, the Houston region also relies on groundwater for domestic and industrial usage.

When a water source becomes polluted or otherwise contaminated, it is considered to be impaired. In heavily populated areas like Houston, the most common contaminants of groundwater come from petroleum storage tank facilities.

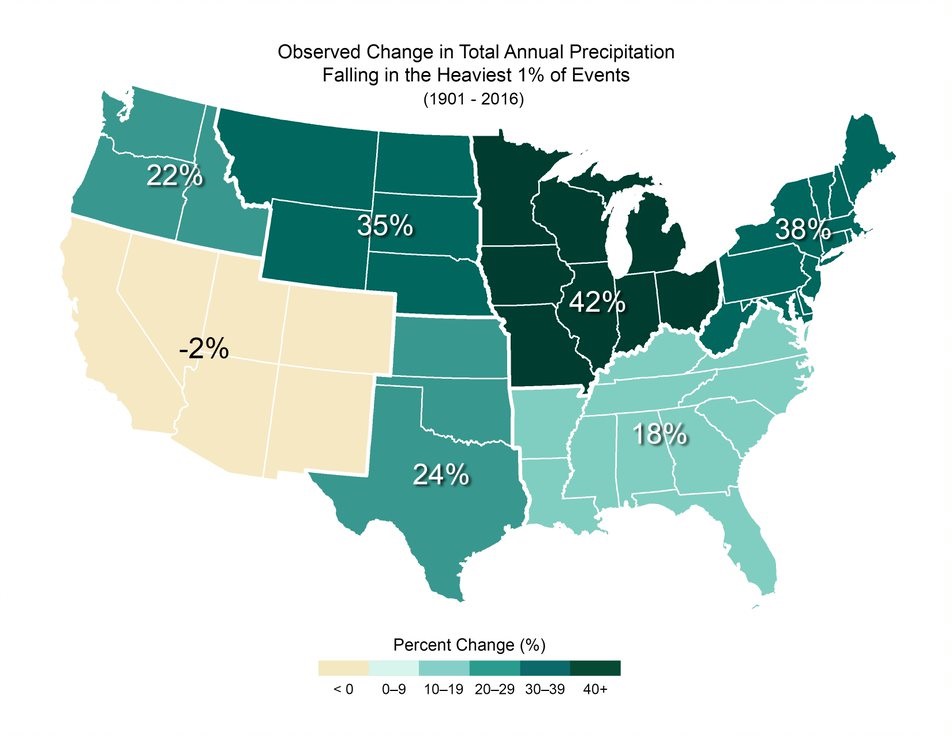

What does this mean for Greater Houston’s water quality? Overall, 67% of the water streams found in the three-county area are currently impaired because of bacterial contamination, making their water unsafe. When bacteria concentrations in the water are too high, people swimming, fishing or boating in the water can become ill if they ingest the water. Some of the most common contributors of bacterial contamination are malfunctioning wastewater treatment plants, sanitary sewer system overflows, and failing onsite sewer facilities and septic systems. Severe storms and flooding can also exacerbate contamination in regional waterways, particularly in regions accustomed to flooding.

Continue reading about flooding in Houston

Harris County has the most miles of impaired streams, about 530 miles in total, compared to 227 miles in Montgomery County and 48 in Fort Bend County. As a percentage of all stream miles, Harris County and Fort Bend have a higher proportion of contaminated streams (71% and 72%, respectively) than Montgomery County (59%). More miles are impaired in Fort Bend and Montgomery counties today than a decade ago with levels in Harris County relatively flat.

Toxic chemicals can be found in our air, water, and land, affecting our collective health

What causes water pollution, other than bacteria? Toxic chemical waste released by industrial facilities also greatly affects Greater Houston’s water quality. In the U.S., industrial facilities that meet certain criteria must report the amount of chemicals that are released into the environment. This information is released to the public through the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). Not all toxic chemicals used in the U.S. are reported. However, TRI does monitor those that may pose a threat to human health and the environment. As of 2021, the TRI chemical list included 770 individual chemicals and 33 chemical categories.

Houston’s three-county region releases a smaller share of chemical waste into the environment than Texas and the nation

Toxic waste from facilities can be managed in different ways. According to the EPA, the preferred management method is recycling, followed by energy recovery, treatment, and as a last resort, disposing or releasing the waste to the environment.

In 2019, Texas ranked 26th highest out of the 56 states and territories nationwide for total on-site and off-site disposal or other releases per square mile. Both Houston’s three-county region (25.9%) and Texas (24.4%) recycle about one-fourth of its toxic chemicals, compared to the national rate of 53%. However, Texas releases a smaller share of these toxic chemicals into the environment. In Texas, 192 million pounds (or 5%) of production-related waste was disposed of or released into the environment. For comparison, the U.S. released 11%.

At a local level, while Harris County released more total waste (46 million pounds) than Fort Bend (2.7 million pounds) and Montgomery (0.7 million pounds) counties, Harris County released a smaller proportion of that waste (3.5%) into the environment. Montgomery County released 12.7% and Fort Bend released 27.3% of its waste into Houston’s environment.

Despite a reduction in chemical releases, millions of pounds of toxic chemicals are released into our environment

A “release” refers to different ways that toxic chemicals from industrial facilities enter the air, water and land. Releases include spilling, leaking, pumping, pouring, emitting, emptying, discharging, injecting, escaping, leaching, dumping, or disposing into the environment. In Texas, of the 158.7 million pounds of toxic chemicals disposed of or released on-site, 57% was disposed of on land, 32% emitted into the air, and 11% was released into the water.

The amount of toxic chemicals industrial facilities released on-site in Houston’s three-county region has declined significantly in the last 15 years. Between 2005 and 2019, the three-county Houston area has reduced the amount of toxic chemicals released on-site by 23.4% from nearly 50.1 million pounds to 38.8 million pounds, respectively. The greatest reductions were seen in the levels released into the air (41.0%) while the amount released in water increased about 10.3% during the same time period. Fort Bend reduced its on-site chemical releases 40.4% between 2005 and 2019 with the substantial reductions across air, water, and land. Toxic chemicals released on site fell 21.5% in Harris County and 62.1% in Montgomery County during the same time period.

More recently, Fort Bend released 2.1 million pounds of toxic chemicals on-site in 2019, with 1.5 million pounds placed in some type of land disposal and 650,000 pounds released into the air. Montgomery had 796,000 pounds of chemicals that were not recycled, recovered, or treated in the same year. Of those, 527,000 pounds were disposed off-site, while 268,000 pounds were emitted on-site into the air. For Harris County, of the 46.6 million pounds of waste either being disposed of or emitted, 22 million pounds were disposed of on land, 10.6 million pounds were released into the air, and 3.6 million were released into water.

Read about renewable energy and climate change in Houston

People of Color are disproportionately impacted by air, water, and land pollution

Black and Hispanic residents are more likely to live in areas with a higher exposure to air, water, and land pollution than white Americans.11 Recent research has also shown that while white Americans cause more pollution through consumption, non-white populations suffer more from that pollution.12

The Department of Energy defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” More succinctly, environmental justice refers to the principle that all people should have access to clean and healthful environments and that the burdens of pollution are not carried by only certain groups. To promote transparency of this issue, the EPA developed EJSCREEN—a publicly-available tool that shows where environmental burdens may not be shared equally.

As part of the EJSCREEN toolkit, EPA created 11 EJ indexes. Each index looks at a single environmental factor and combines it with a demographic component to understand the “excess environmental risk” faced by People of Color and low-income individuals. EJSCREEN allows for comparisons of a community to the rest of the state, EPA region, and nation, by using percentiles. A percentile is a relative term, and tells us how an area’s performance compares to a particular group (e.g., other counties in Texas, other counties in the U.S.). So, a county with a percentile of 80 on a particular EJ Index means that the county has higher risk on that environmental factor given its demographic composition than 80% of other counties in Texas (or the nation, depending on the comparison).

When compared to the rest of the state, Fort Bend and Harris counties are worse than the median in each of the five air-quality measures, meaning they’re worse not only because of Houston’s air quality itself, but also because of the racial inequality in exposure to those hazards compared to other counties in Texas. Fort Bend County performs worse than 71% of other counties in Texas on particulate matter (both the levels and the excess risk borne by People of Color and low-income communities). However, when compared to the nation, Fort Bend County performs worse than 86% of counties. While Montgomery County performs better than most other Texas counties on the same measures, Montgomery County has the least racial/ethnic diversity among the three Houston-area counties which affects its score.

Similar trends emerge for EJ indexes that focus on waste and water quality. Proximity to superfund sites on the National Priorities List (NPL) is higher for all three counties compared to the rest of the state and nation. Fort Bend and Harris also have higher environmental justice issues surrounding hazardous waste facilities and sites that use certain flammable and toxic substances, also known as Risk Management Plan sites. One area where all three counties in the region perform better than other counties in Texas and the U.S. is in wastewater discharge.

EJSCREEN also produces maps that show which block groups have disproportionate risk to unhealthy environments. The higher the percentile, the higher the environmental harm to People of Color and low-income populations relative to the state (or nation).

Helpful Articles by Understanding Houston:

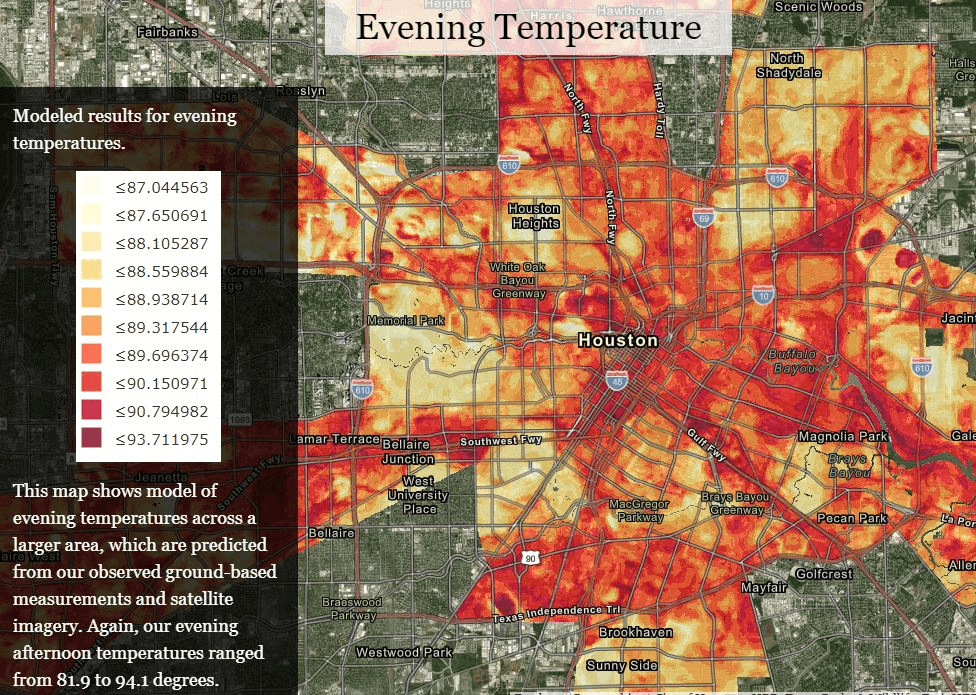

- Houston is Hot

- Four Facts About Houston’s Environment That Every Resident Should Know

- The State of Water Quality in Houston: Four Stats Every Resident Should Know

- Examining Houston’s Reputation as a Car City

References:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Ground-level Ozone Pollution – Health Effects of Ozone Pollution,” last modified May 5, 2021.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Air Quality Criteria For Ozone And Related Photochemical Oxidants (Final Report, 2006), by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA/600/R-05/004aF-cF), Washington, DC, 2006. Web.

- Bullard, R. D. (1983). Solid waste sites and the black Houston community. Sociological inquiry, 53(2‐3), 273-288.

- Bullard, R. D. (Ed.). (1993). Confronting environmental racism: Voices from the grassroots. South End Press.

- U.S. EPA. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants (Final Report, Apr 2020). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-20/012, 2020.

- Zhe Jiang, Brian C. McDonald, Helen Worden, John R. Worden, Kazuyuki Miyazaki, Zhen Qu, Daven K. Henze, Dylan B. A. Jones, Avelino F. Arellano, Emily V. Fischer, Liye Zhu, K. Folkert Boersma. “Unexpected slowdown of US pollutant emission reduction in the past decade.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018; 201801191 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801191115

- U.S. EPA. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter (Final Report, Dec 2019). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-19/188, 2019.

- Clay, K., Muller, N. Z., & Wang, X. (2021). Recent increases in air pollution: evidence and implications for mortality. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 15(1), 154-162.

- Shaddick, G., Thomas, M.L., Mudu, P. et al. Half the world’s population are exposed to increasing air pollution. npj Clim Atmos Sci 3, 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-0124-2

- Craun, Gunther F., et al. “Causes of outbreaks associated with drinking water in the United States from 1971 to 2006.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 23, no. 3 (2010): 507-528.

- Brulle RJ, Pellow DN. “Environmental justice: human health and environmental inequalities.” Annu Rev Public Health. 2006; 27:103-24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102124. PMID: 16533111.

- Tessum et al., “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure.” PNAS March 26, 2019 116 (13) 6001-6006; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818859116.