Houston has certainly earned its reputation for resilience. Since 1980 the region has been hit by 26 natural disasters, including five hurricanes, five tropical storms, two wildfires, a dozen rain/flood events and a winter storm, to name a few. Nearly a third of these disasters have occurred since 2015, and yet the population continues to rise, and the three-county area has added jobs at a rate faster than the nation.

You’ve likely seen the “Houston bounces back” or “Houston Strong” messaging, but in a region celebrated for its resilience, not everyone bounces back equally after disaster strikes. What factors contribute to our ability to recover from the many ways disasters wreak havoc on our lives? It is important that, while acknowledging Houstonians’ resilience, we discuss the wide-ranging impacts behind the disasters that are often hiding behind the resilience narrative. The human experiences behind these disasters and the data we gather in their wake can both tell us more about what it is that makes Houston resilient and how we can better prepare for the future.

Uneven recovery, ongoing risk

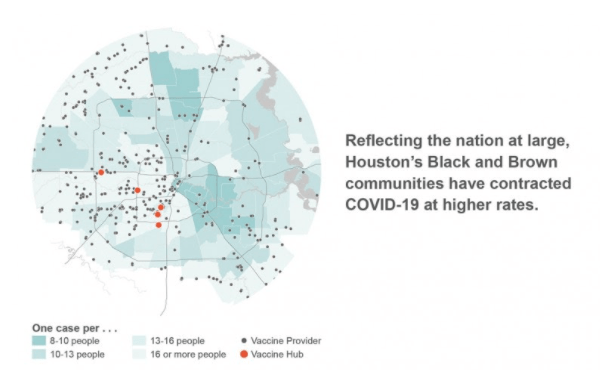

About one in five residential properties are at risk of flooding in Houston’s three-county area, and 286,000 properties are projected to have “substantial” risk of flooding by the year 2050. A figure made more disquieting by the fact that communities most vulnerable to flooding are the least likely to recover. Historically, these neighborhoods are on low-lying land, receive fewer public flood mitigation projects, and are characterized by decades of disinvestment, such as poor stormwater infrastructure.

On top of that, residents of these communities are overwhelmingly low-income, immigrants, and historically marginalized, meaning they typically have the fewest resources available to prepare in advance of a storm and to help them recover from its effects once it passes.

One year after Hurricane Harvey, the Episcopal Health Foundation conducted a survey that found that Black, low-income and immigrant families were most likely to report that they did not receive financial aid after the storm or that the financial aid they did receive covered “very little” or “none” of their financial losses. They were also more likely to report that they weren’t getting the help they needed to recover. These sentiments are validated by established research that shows that federal disaster assistance policies place vulnerable groups at a disadvantage and reduce their ability to access resources and assistance for recovery. More specifically, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh and Rice University found that wealth inequality increased in counties hit by more disasters. In Harris County, the wealth gap between Black and white families increased by an average of $87,000 from the effects of disasters alone.

Hurricane Harvey

Hurricane Harvey is estimated to be the second-costliest storm in U.S. history, causing about $125 billion in damage, and displaced tens of thousands of people over its six days of landfall. The challenging nature of disaster relief is plain to see when staring down a number like $125 billion.

The federal response to Hurricane Harvey was historic. The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) distributed $918.2 million in aid from its Individual and Household Program (IHP) directly to residents of the three-county area after Harvey, and the Small Business Administration (SBA) issued $1.5 billion in low-interest, long-term loans to homeowners.

Both local government and private philanthropic dollars also play a significant role in immediate relief after disasters. Local government provides for the basic necessities of those families waiting on applications to be approved and disbursements to be released, and dollars from the private sector often serve as emergency funds for the particularly vulnerable, particularly those who have not historically accessed public benefits. Collectively, philanthropic funds to support recovery from Hurricane Harvey reached about $971 million following the storm.

Still, nearly one in five (17%) Harris County residents reported that their quality of life was worse one year after Harvey as a direct result of the storm, with Black (31%) and low-income (20%) households bearing the brunt of the effect on the region.

COVID-19

Though the Houston region has plenty of experience activating after a storm, we had never responded to a public health disaster of this scale. But the region responded quickly in March 2020 by adapting our weather-related disaster expertise to a pandemic. Our ability to be nimble and flexible in responding to the effects of COVID-19 revealed both strengths and gaps in our resilience.

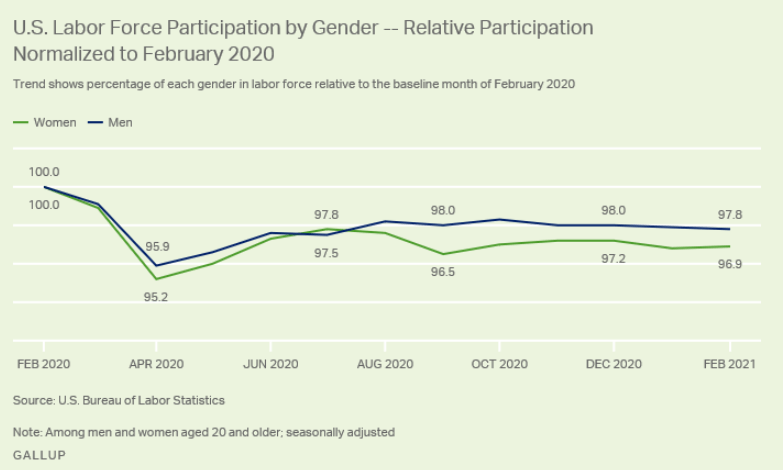

Not only were people getting sick and dying, our region suffered significant job loss, with unemployment peaking in April and May of 2020 at 14.6% in Harris County. Households with low incomes were the most likely to lose their jobs. One in five renters still reported that they were behind on payments in December 2021, almost two years after the onset of the pandemic. The Houston Metro Area has the highest rate of reported food insecurity, among the 15 most populous metros 15 times out of the first 40 surveys conducted by the Census Bureau, with the highest rates among non-white households and households with children.

The challenges were enormous, and our region quickly responded with innovative relief funds and programs. This is not an exhaustive list, of course, but here are just a few:

- The COVID-19 Emergency Rental Assistance Program, funded by Harris County and the City of Houston, aimed to bring financial relief to thousands of tenants impacted by the health and economic impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic. The program has provided nearly $280 million in rental assistance to almost 70,000 households impacted by COVID-19 since it launched in February 2021. The funds have been distributed by three agencies with established experience in helping people in need: BakerRipley, Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, and The Alliance.

- The Harris County COVID-19 Relief Fund, funded by Harris County, provided $60 million in funding to support residents in need. A total of 40,000 eligible households received a one-time payment of $1,500 for emergency expenses. This fund was administered by Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston.

- The Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund, established by Greater Houston Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Houston, has invested $18.4 million in 87 nonprofit partners that were able to serve about 210,000 individuals living in 100,600 households located in Fort Bend, Harris, Montgomery and Waller counties

- The majority of folks who lost their jobs at the beginning of the pandemic worked in hospitality and retail. The Get Shift Done program paid for out-of-work hospitality workers to staff food pantries — this served the dual purpose of responding to the skyrocketing demand for food donation while also providing living wages to folks who were laid off.

- The Lost Loved One Fund, funded through the Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund and administered by Memorial Assistance Ministries provided flexible financial assistance to families that lost a primary breadwinner or immediate family member due to COVID-19.

- To combat food scarcity, the Urban Harvest Community Gardens Program, one of many agencies addressing food insecurity in the region, donated 136,000 pounds of food in 2020 alone, and the Houston Eats Restaurant Support program raised almost $5 million to provide for food-insecure individuals.

- Through a systems investment from the Greater Houston COVID-19 Recovery Fund, Connective has been developing coordinated social service and financial assistance programs for Texas Gulf Coast Residents in need. Read more about their work here and learn about how they are reimagining how disaster services are delivered in the region with residents at the center of it all.

Winter Storm Uri

Most recently, Winter Storm Uri brought nearly unprecedented challenges in February 2021 to a region already well-acquainted with natural disasters.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimates the true costs of Winter Storm Uri to be somewhere between $80 and $130 billion, which would make it potentially the most costly weather disaster in Texas history. The storm left millions of people without power and water, causing damage in patterns not dissimilar to those of previous disasters in that vulnerable communities were affected disproportionately.

In response, Mayor Sylvestor Turner and Judge Lina Hidalgo quickly established the Houston Harris County Winter Storm Relief Fund, which the Greater Houston Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Houston jointly administered. The first round of emergency financial assistance was distributed within four days to pre-existing nonprofit partners with a proven record of disaster response — a pace faster than any previous local disaster response.

To help low-income homeowners repair damage caused by burst pipes and other effects of the ice storm, the Winter Storm Relief Fund supported an innovative program from Connective, a local nonprofit, that connects families in need with home repair agencies. Connective’s work streamlines the home repair process by serving as a one-stop shop for families and bringing increased accessibility to social services through their knowledge of the disaster relief cycle and cutting-edge, human-centered technology.

Resilience for all

True climate resilience, however, is ultimately about not only ensuring the most vulnerable in our region are able to recover from disasters quickly, but also anticipating and preparing for the worst. Residents who are economically, housing, and food secure before disaster strikes are most likely to recover from the negative impacts of disasters in the shortest amount of time.

Houston has certainly earned its reputation for responding quickly and effectively after crises, but the future of reaching true climate resilience will require transformative systems/ infrastructure change, public investment in areas and communities most at risk, and philanthropic dollars that spur innovation. Still, Houston is strong, as are the people who call it home, and our collective capacity for innovation, empathy and hard work will always remain a hallmark of our region.