“This is the city where the American future is going to be worked out,” Stephen L. Klineberg, Ph.D., said of Houston in 2010. Klineberg, the founding director of Rice University’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research, has been tracking the ways in which Houston has been changing since the 1980s through the Kinder Houston Area Survey. Understanding Houston, like the Kinder Institute, believes that data helps tell our region’s story and provides a barometer with which we can measure how we change over time. Our region is of such consequence not only because of our size and demographics, but also because of strengths like our industrial diversity and the opportunities we have to address our region’s unique vulnerabilities.

Houston’s population growth, population change

Greater Houston’s population has changed significantly over the last few decades, a trend that will inform the other ways in which our region will continue to evolve and grow.

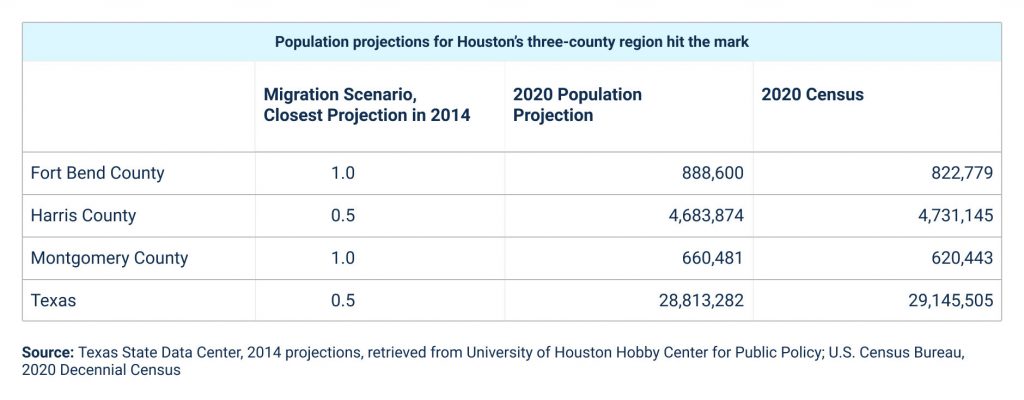

Houston’s three-county region has added over one million residents since 2010, with each county seeing significant population increases. Population growth comes from two sources: natural increase and net migration. Natural increase refers to the number of births minus the number of deaths, and it is relatively predictable. Net migration, both domestic and international, is more affected by external factors, such as cost of living, the regional economy and public policy.

The U.S. Census Bureau distinguishes between domestic and international migration when calculating net migration. According to Census Bureau data, Harris County, the most populous of Houston’s three-county region, experienced significant negative domestic migration between 2010 and 2020. Approximately 80,000 more people left Harris County to live elsewhere in the U.S. than moved into Harris County from somewhere else in the country over the ten-year period.

Despite the negative domestic migration, Harris County (and the region overall) continues to grow at a rapid rate. This is due to both the natural increase and high levels of international migration — Harris County gained 289,400 residents from international migration over the ten-year period. The population in Houston hasn’t just grown, however, it has fundamentally changed.

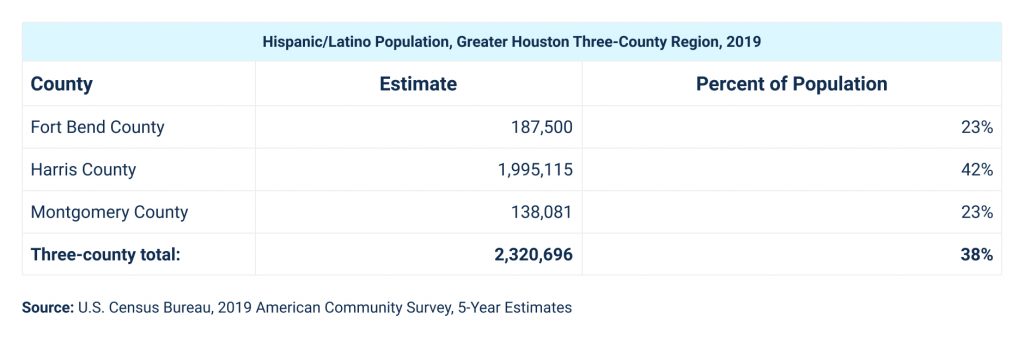

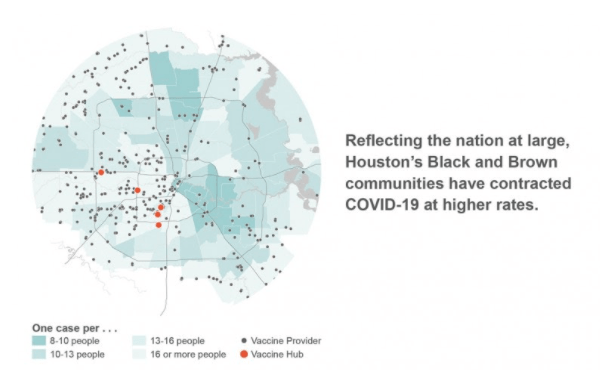

More than two-thirds of Houston’s three-county region is now made up of people of color, marking a complete demographic transformation from the region’s racial/ethnic composition just 40 years ago. The largest contribution to this immense shift has been the growth of people who identify as Asian American or Hispanic, who now comprise 47% of the population of Houston’s three-county area, up from 16% in 1980.

Increasing industrial diversity

Houston has a reputation for being an energy town. This reputation, while not entirely unearned, is limited in its assessment of the Houston economy. Houston ranks third among U.S. metropolitan areas in number of Fortune 500 headquarters, and received half a billion dollars in venture capital funds for the tech sector in 2019 alone.

The jobs in Houston’s three-county region have also changed. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of people employed in management of companies and enterprises increased five-fold to 43,000 in 2020 from 8,000 only 20 years ago. And jobs in agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting in our region have fallen 40% to 28,000 in 2020 from 45,600 in 2000, according to the Quarterly Census for Employment and Wages. Perhaps most concerning, manufacturing jobs in the region have also fallen 7% in that same time period. Further, job growth in Texas and the three-county region has outpaced the national rate in all major industries but healthcare and social assistance, though that industry now employs 13% of our region’s workforce compared to 9% in 2000.

Healthcare and social assistance jobs, however, are more likely to qualify as ‘“opportunity employment.” Opportunity employment refers to the jobs accessible to workers without bachelor’s degrees that pay above the national median wage and reflect the local cost of living. In the Houston metro area, 24% of employment was classified as opportunity employment in 2017, while 27% of jobs required a bachelor’s degree, and 49% of employment was considered lower-wage.

Climate change and environmental progress

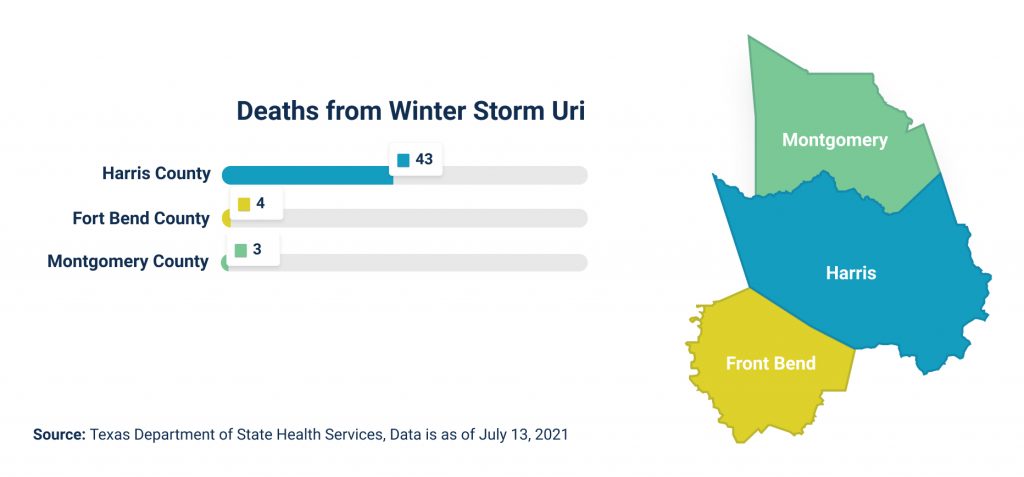

It would be impossible to discuss the region’s evolution over the last few decades without mentioning our relationship with the environment, natural disasters and shifting climate patterns in Houston. The region continues to feel the effects of more frequent and severe storms, which have shaped the region in many ways — some more obvious than others.

Although many in the region have grown accustomed to the oppressive Houston heat, Houston is demonstrably hotter than it was a decade ago, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The 30-year average temperature in our region increased between 0.6 and 1.0 degrees Fahrenheit between 2010 and 2020 — unwelcome news to residents who live in a region that can be dangerously hot. Montgomery County had over 500 days at temperatures above 95 degrees Fahrenheit in the last decade, compared with fewer than 300 days the previous decade. That is almost two-thirds of a year of extra extreme heat over a single decade.

The numerous and recent natural disasters our region has experienced have also changed us. (And the National Weather Service.) FEMA has declared a disaster in our region eight times since 2015, and more are likely to come our way given predictions that warmer temperatures will continue to cause stronger hurricanes. But Houstonians by and large know that now; in 2019 53% of Houstonians participating in the Kinder Houston Area Survey reported that the shifting climate patterns is a serious threat, up from 39% in 2010.

At the same time, we have made major strides in improving our region’s air and water quality. For example, between 2000 and 2020, levels of harmful particulate matter fell 23% in the Houston Metropolitan Area. Texas also produces a larger share (23%, nearly double the national rate) of its energy from renewable resources than the rest of the nation. Living up to its reputation as a city ready to embrace change, the City of Houston announced its Climate Action Plan, aiming to further reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Changing perspectives and behaviors

We’ve seen how the region’s demographics, industry and environment have evolved over the last few decades, but how have Houstonians’ behaviors, opinions and attitudes changed?

Resident priorities have changed in the past 10 years in many meaningful ways. Voting in Houston has experienced a surge in popularity, with voter registration rates at an all-time high, in keeping with the country’s increased participation throughout the pandemic and in the 2020 election. Voter turnout increased by almost 10 percentage points in Fort Bend County between the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections and 7.8 points in both Harris and Montgomery counties. Houston voters still lag behind the rest of the country in voter turnout, but the region is making progress.

The region has also gone through some important ideological changes related to sustainability and urban innovation. Metro’s light-rail service and bus routes have been expanded, and Houston BCycle, a local non-profit bike-share program, has seen rider numbers spike. Houston Parks Board has introduced their Bayou Greenways Plan in an effort to create and connect a navigable greenspace through the system of bayous running through the city.

Some of the most profound shifts in our region are also some of the least visible. Gradual changes in ideology have also taken place. For example, support for same sex marriage in the Houston area has more than doubled in the last few decades, growing to 64% in 2019 from 31% in 1993, according to the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey.

The effects of a diverse population may have inspired another change; 71% of U.S.-born non-Hispanic white adults in Harris County are in favor of granting undocumented immigrants a path to legal citizenship if they speak English and have no criminal record, up from 56% in 2010.

Despite our challenges, the proportion of Houston-area residents who say the region is a “good” or “excellent” place to live has increased to 76% in 2020 from 59% in 1983, according to data from the Kinder Houston Area Survey.

Houston’s resilience won’t change

Change can be unsettling, but it can also represent growth and improvement. As much as our region has already changed, we know more is still to come — some changes we may reasonably predict while others may completely surprise us. And in the face of all this change, we look to one constant aspect of our region: resiliency. Whatever may come our way, we know that armed with the right information and resources, community leaders and residents alike can help Houston thrive through whatever may come next.

Helpful Articles by Understanding Houston: