Banner photo: Carrie Rai, FBCHHS Performance and Innovation Specialist

This article is the first of a two-part series that describes the community engagement plan and process to create Fort Bend County’s first Community Health Assessment and Health Improvement Plan since 2007.

In the summer of 2022, Fort Bend County Health & Human Services (FBCHHS) completed its first Community Health Assessment (CHA) in 15 years. The Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) defines a CHA as “an assessment that identifies key health needs and issues through systematic, comprehensive data collection and analysis. The ultimate goal of a community health assessment is to develop strategies to address the community’s health needs and identified issues.”

The Process

FBCHHS followed the Association for Community Health Improvement Community Health Assessment Toolkit to guide the CHA process.

The CHA process was a collaborative effort, led by FBCHHS. The process of collaboration and community engagement began with identifying stakeholders from a variety of sectors within the community and the creation of the CHA Committee.

The committee was comprised of FBCHHS divisions and leadership and division representatives alongside community stakeholders representing primary health care, mental health, hospitals, private philanthropy, local government, non-profits, the faith community, academia, transportation, and public safety.

The committee was integral in guiding the process of the CHA, providing input for and reviewing the methodology, data, analysis, as well as determining the types of secondary data to collect, and what questions to ask in the survey and the key informant interviews. The CHA committee also made suggestions about who to interview and how to administer the survey.

More than 150 Fort Bend County leaders, residents, stakeholders and health champions and over 70 organizations attended the community input sessions throughout the CHA and community health improvement planning process. Additionally, FBCHHS conducted 25 key informant interviews and administered 845 surveys. These activities provided a platform for diverse agencies, community members and perspectives to be shared to generate inclusive, cohesive and attainable health improvement goals.

Community Health Priorities

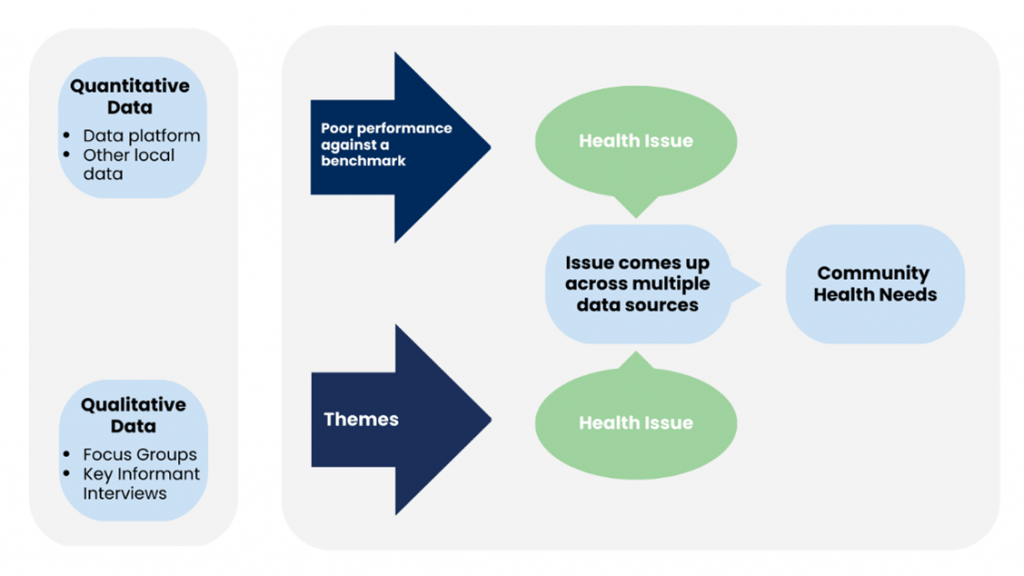

FBCHHS used the Kaiser Permanente National Community Benefit decision-making criteria for the identification and prioritization of health needs. Quantitative data was compared against the following benchmarks: the state of Texas, U.S. as a whole or the top 10% performing U.S. counties. A health issue was identified when there was poor performance across the comparative benchmarks. Health issues were also identified through thematic analysis of qualitative data from input sessions and Key Informant interviews. Community health need priorities were determined when the same health issue was identified in both the quantitative and qualitative data.

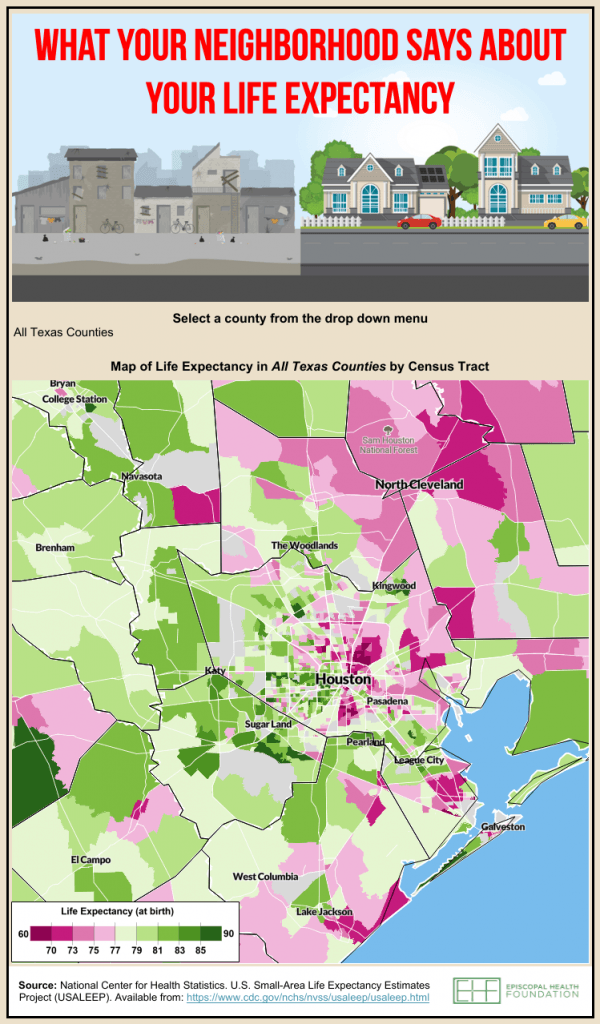

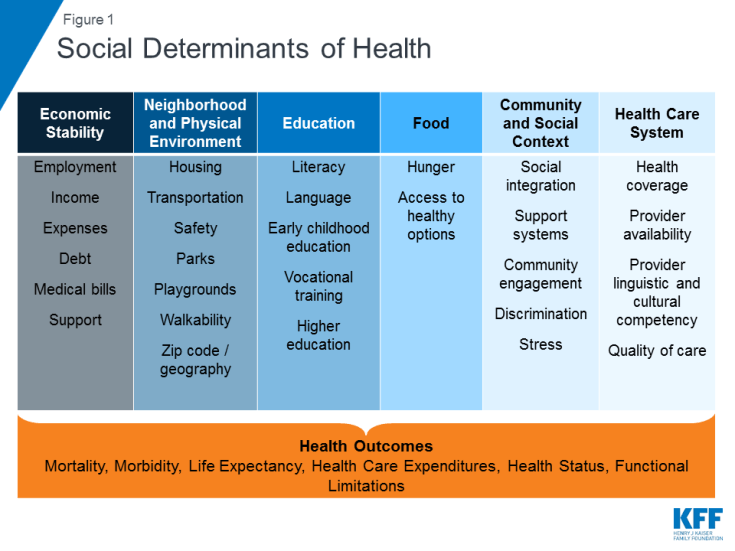

According to the 2022 County Health Rankings, Fort Bend County ranks fourth in the state for best overall health outcomes. However, the CHA data illustrates areas for improvement among vulnerable populations that have disproportionate health outcomes. Black and Hispanic populations, people without health insurance, and people with low-income have poorer health outcomes. These groups struggle to access services, contributing to health disparities.

While there are several areas where Fort Bend County could see improvement, residents, community leaders and stakeholders identified five top community health priorities.

Mental Health

Like physical health, mental health is critical to our overall well-being. Good mental health affects our thoughts and behaviors, helps us maintain fulfilling relationships, enables us to cope with change and adversity, and ultimately supports our contributions to society. Mental health is also closely connected with physical health. Poor mental health may lead to behaviors that harm physical health (e.g., alcohol and other substance use, lack of exercise, etc.), and having poor physical health can negatively affect our mental health. About one in four survey respondents stated that their mental health was not good for one to five days out of the past 30, and 46% said mental health has been a problem in their household.

About one in seven survey respondents stated that there was a time in the past year that someone in their family needed mental health services but couldn’t receive them — either because they couldn’t afford to pay (34%) or the wait times were too long (27%). Overall, one-third indicated that mental health services are missing in the community. The data from surveys reflect mental health access challenges we see in Fort Bend, specifically. Within Houston’s three-county region, Fort Bend has the highest ratio of residents to mental health care providers, though there has been improvement since 2017.

Housing

Affordable, safe, and stable housing is a basic need, and unsafe or unstable housing threatens our health, well-being, and economic security. At the same time, the cost of housing is the single largest expense for most households, and it has become increasingly unaffordable in recent years. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development considers affordable housing as not more than 30% of income. If a household spends 30% or more of their income on housing costs, they are “housing cost burdened.” Households that spend 50% or more of their income on housing costs are “severely cost-burdened.”

Renters are much more likely to be burdened by housing costs than homeowners. In 2021, more than 45% of renters were cost-burdened compared to 25% of homeowners; and 22% of renters were severely cost-burdened compared to 11% of homeowners. While the share of homeowners who are cost burdened has fallen since 2010, renters are more likely to be cost burdened now than a decade ago. Additionally, a person would need to work 3.2 full-time jobs at minimum wage to afford a two-bedroom rental property at Fair Market Rent in Fort Bend County. Fort Bend County’s population has already increased 41% over the last decade and is expected to increase an additional 15% to nearly 1 million by 2030, according to the Texas Demographic Center’s recent projections. Given these data, it is not surprising that one-third of survey respondents indicated affordable housing is missing in Fort Bend and more than half of Key Informant interviewees cited the issue as their top concern.

Obesity

Obesity, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or more, is a complex health condition affecting both adults and children. Obesity increases the risk for health conditions such as coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, hypertension, and more. Obesity is found to take more years of life than diabetes, tobacco use, hypertension, or high cholesterol.

Nearly 30% of adults in Fort Bend County are classified as obese, according to County Health Rankings, and the disease was the top health issue identified among survey respondents. While not the only related triggers, poor eating habits and lack of exercise can contribute to obesity. About 40% of survey respondents are concerned with poor eating habits and 39% are concerned with a lack of exercise.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Heart disease was the fifth most-cited health issue by survey respondents and Key Informants with more than one in seven identifying the diseases as a health concern. White and Black residents of Fort Bend die from heart disease at significantly higher rates than Asian and Hispanic residents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER data tool.

The National Center for Health Statistics shows that three out of 10 deaths in Fort Bend County are attributed to heart disease and stroke. However, we know that many patients with heart disease also suffer from other chronic conditions, including lower respiratory diseases, diabetes, and kidney diseases, which comprised an additional 6% of deaths in 2020.

Maternal Health/Prenatal Care

Babies who are born in good health and who continue to thrive with positive experiences, tend to grow into healthy and productive adults who sustain our population and contribute to our economic vitality. Of course, a newborn’s health depends not only on the mother’s health during gestation but also her state of health before pregnancy. Early prenatal care is defined as pregnancy-related care beginning in the first trimester (1-3 months) and has been viewed as a strategy to improve pregnancy outcomes for more than a century.

In 2020, the rate of women who receive late (after the first trimester) or no prenatal care in Fort Bend County (30%) is three times that in Texas (10%) and five times the rate in the U.S. overall (6%). Between 2019 and 2020, Fort Bend saw an unprecedented 10-percentage-point decline in the proportion of women who received early prenatal care — a drop we didn’t see in neighboring counties despite the pandemic. Black and Latino women in Fort Bend had the lowest rates of early prenatal care, which is not surprising because a lack of health insurance is the largest contributor to women delaying or not accessing prenatal care, and women in those groups have the lowest rates of health insurance coverage.

Community Mobilization for Change

Through the CHA organizations, community members, and other stakeholders are able to evaluate the health of communities, factors that contribute to health challenges in Fort Bend County, existing community assets and resources to improve the community’s health can also be identified. The Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP) contributes to the advancing of strategies to shorten the gap to accessing services, resources, and disparities faced with the top five community health priorities. The CHIP brings focus to the health issues identified in the CHA and allows communities, municipalities, jurisdictions, and community partners to actively collaborate and create a united plan to improve the health of Fort Bend County.

Healthy communities do not happen on their own, but through the efforts of community mobilization, local government support and key stakeholder contributions. Key stakeholders include local elected officials, hospital partners, FQHCs, foundations, non-profits, religious organizations, school districts, HOAs and many others. The shared goal is always to increase the quality of health across Fort Bend County.

We invite you to join us in reducing the gap for accessing services and or providing resources for the community members to meet the needs identified from the top five health priorities. FBCHHS Office of Communications, Education and Engagement is available to present to your organization or business about the CHIP to bring further awareness on how your organization or business can aid the community members of Fort Bend County.

Please email hhsoutreach@fbctx.gov to request a presentation.

Please access the full Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan at http://www.fbctx.gov/cha!