Where we live profoundly affects nearly every aspect of our lives, including the quality of education we receive, the availability of good-paying jobs, access to high-quality healthcare and fresh food, and more. One year into the pandemic, it is also evident that the neighborhood we live in influences our chances of catching COVID-19 and getting vaccinated. But where we live also determines the quality of air we breathe, the water we drink, and ultimately, our health. This environmental inequity is the legacy of racial segregation without significant intervention.

Environmental racism refers to the fact that marginalized communities — communities of color, and low-income families — are disproportionately impacted by environmental hazards. In practice, patterns of environmental racism can be observed in the deliberate placement of toxic waste dumps and industrial facilities in and near predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods, which has a disproportionate negative environmental and health impact on these communities.

Though far from the only major metro to feature environmental inequity, Greater Houston’s many industrial facilities make these issues particularly pronounced within our region. Battling environmental racism and its many impacts requires recognizing those impacts as they exist today and taking informed action. Though environmental racism in Houston is a multifaceted issue, these four trends are an effective starting point for anyone interested in working toward better outcomes for all Houston communities.

Environmental racism disproportionately harms communities of color

One of the most prominent examples of environmental racism in Greater Houston is the deliberate placement of toxic waste dumps and industrial facilities that emit high levels of pollution in and near predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods. The injustice of this is particularly salient since these communities are not themselves responsible for causing the majority of environmental hazards.

In the United States, Black people are exposed to 21% more pollution even though they produce 23% less pollution than the average.1

This inequity is especially true in Houston. As of 2019, 21 industrial and toxic waste facilities are located within three miles of the Harrisburg/Manchester neighborhood, including large-quantity generators of hazardous waste and waste treatment and disposal facilities.2 Hispanic residents comprise 90% of the population of Harrisburg/Manchester and Black residents make up 8%.

But environmental racism isn’t restricted to the placement of toxic waste facilities — it is also true of the placement of chemical plants and oil refineries that emit airborne pollutants in and near communities of color. Houston’s reputation as the “energy capital of the world” makes the problem more potent, given the large number of oil and gas refineries and plants operational in the area.

Chemical plants and oil refineries in the greater Houston area are also overwhelmingly located close to or within communities of color. A large number of plants and refineries are located along the Houston Ship Channel, which is bordered by neighborhoods such as Harrisburg/Manchester and Galena Park, which are 90% and 80% Hispanic, respectively. Almost 40% of Galena Park residents and 90% of Harrisburg/Manchester residents live within one mile of an industrial facility.3 These communities are disproportionately exposed to toxic substances and emissions compared to predominantly white communities. Industrial facilities in Houston emitted an additional 23 million pounds of pollutants over what they were allowed in 2019 alone.

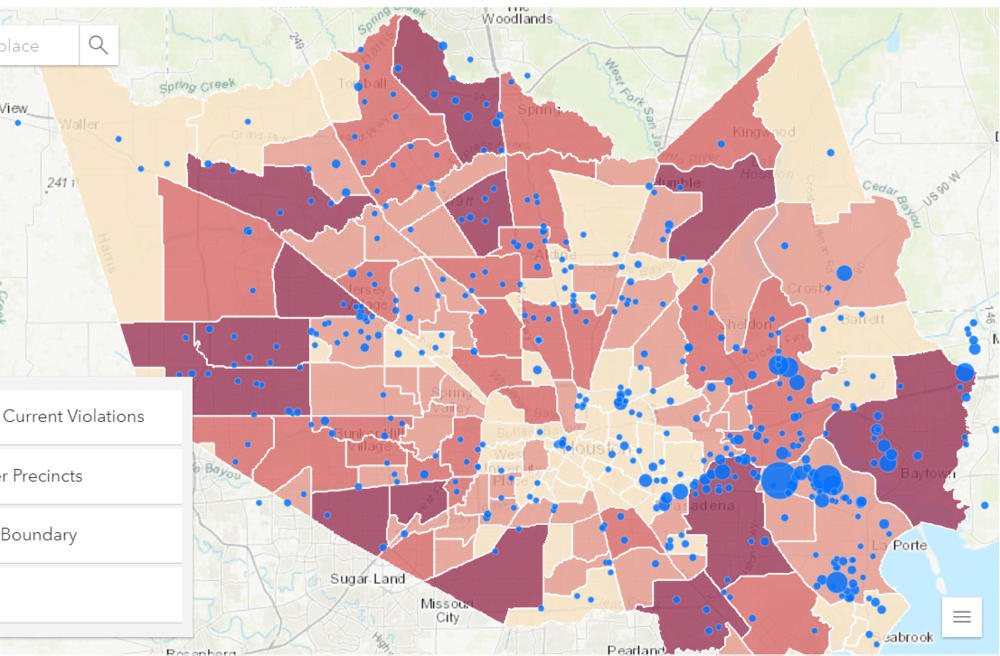

In addition to elevated levels of air pollution and toxic emissions these plants create on a daily basis, chemical accidents are often a regular occurrence. In Houston, a chemical accident occurs about once every six weeks. And unfortunately, as shown in the map below, we have a considerable issue with facilities located in lower income communities of color that have several facility violations that indicate ongoing safety and compliance issues that endanger human health.

Proximity to industrial facilities harms resident health

Industrial facilities emit toxic pollutants in the air and nearby bodies of water, which can have detrimental impacts on the health of the residents. Greater exposure to toxic spills and elevated levels of air and water contamination have been associated with short and long-term health problems.

Residents who live close to chemical plants and industries suffer from a “double jeopardy” — not only are they at a higher risk of health problems including cancer and asthma from the elevated levels of air pollution and toxic emissions these plants create on a daily basis, they are also at a higher risk of being exposed to chemical accidents, which can be potentially life-threatening for those who live in close proximity.4

The communities in close proximity to industrial facilities are also at higher risk for respiratory problems, cancer and other chronic conditions than other Greater Houston residents.

In Houston, Black children are more than twice as likely to develop asthma than white children.

The presence of industrial facilities in Harrisburg/Manchester puts its residents at a higher risk for various diseases — the residents are at 22% higher risk of cancer than other residents in Houston.

The presence of “cancer clusters” among communities of color in Houston is troubling. Cancer cluster is a term referring to areas plagued by a higher-than-expected number of cancer diagnoses, typically due to environmental factors. Cancer clusters have been identified in Fifth Ward and Kashmere Gardens, both predominantly Black neighborhoods, according to the Texas Department of Health Services. The increased incidence of cancer has been linked to the emissions by the railroad industry that was located and operational in the area during the 1900s.

The placement of industries that emit substantial pollutants in communities of color isn’t accidental

The deliberate placement of industrial and waste facilities within communities of color and away from historically white neighborhoods forces the question: who benefits, and at whose expense?

Decades of discriminatory policies and structural barriers have been instituted to maintain racial segregation. The government-sanctioned policy of redlining and racial zoning in particular helped cement environmental racism. As part of redlining policies, Black neighborhoods were designated as “risky investments” to prevent banks from making home loans and other investments in the area. This policy of designating these areas in red on maps successfully directed all investment and infrastructure away from it, leading to the degradation of historically Black and Brown neighborhoods. Public officials then offered up these redlined neighborhoods as locations for “undesirable” industries such as landfills and chemical plants.5

One of the first initiatives to tackle environmental injustice in civil court was Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation (1979), in which residents of a predominantly Black community in Northeast Houston challenged the company’s decision to build a waste disposal site in the neighborhood. One of the lead plaintiffs, Dr. Robert D. Bullard, who’s widely known as the father of environmental justice, set out to learn if that decision was “random or part of a pattern of discrimination.” He found there was a “clear racial pattern.” Between 1930 and 1978, Black residents made up only 25% of the city’s population, but 82% of the city’s waste was dumped in predominantly Black neighborhoods, even those with higher income. Despite resistance from the residents, race was still one of the most potent factors in predicting who was getting dumped on.

Environmental racism is compounded by climate change and natural disasters

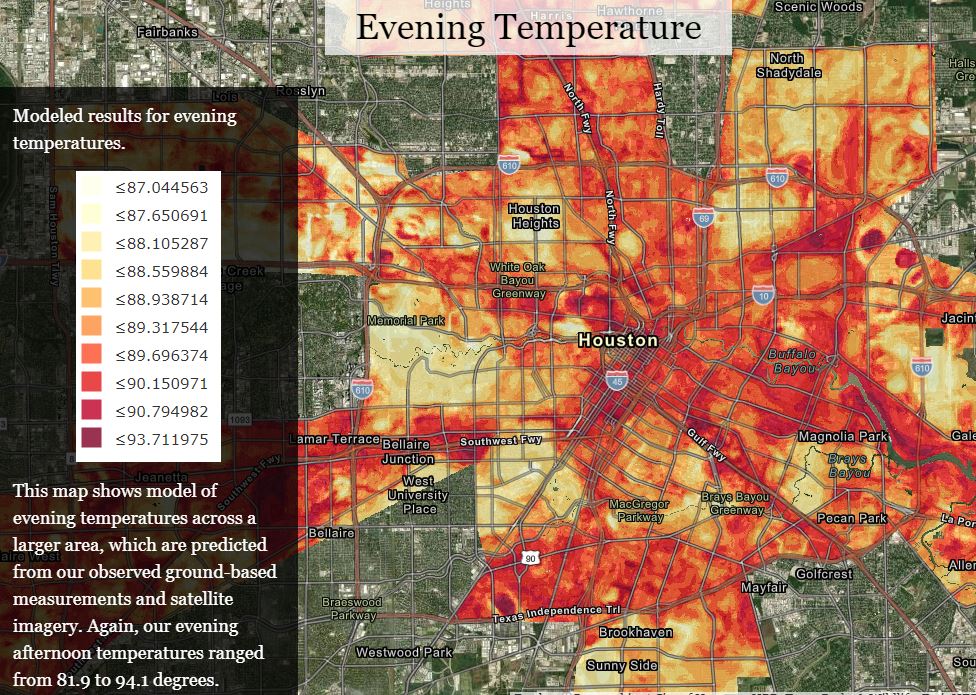

The problem of environmental racism becomes more pressing within the context of accelerating climate change. In an investigative report, the New York Times explored how redlining and racial zoning has resulted in Black neighborhoods experiencing temperatures that are “5 to 20 degrees higher” than white neighborhoods. These historically redlined neighborhoods lack trees, parks and shade, that help keep temperatures bearable on extremely hot days.

Source: Houston Harris Heat Action Team

This is also true in Houston. An analysis of nighttime temperatures in Houston neighborhoods shows that the highest temperatures are concentrated in several low-income neighborhoods, many of them a product of redlining. This puts residents at a higher risk for heat-related health hazards.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has predicted a temperature increase of 2.5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next century. The extent of climate change impacts on individual regions will vary, however, depending on the region’s ability to mitigate or adapt to changes. IPCC has also predicted an increase in heavy precipitation events, increasing sea levels, and more frequent and intense hurricanes. Rising sea levels along the Houston Ship Channel are likely to expose an additional 35,000 residents in the nearby communities to regular flooding by 2050.6 Given these forecasts, certain communities will bear the brunt of these disasters, further exacerbating the effects of environmental racism in Houston and across the country.

The frequency and intensity of natural disasters have already increased in the country over the past decade. Greater Houston has experienced eight federally-declared disasters since 2015, including the COVID-19 pandemic, and Hurricane Harvey’s devastating flooding. Fenceline communities, those that live next to industrial facilities, face larger risks from natural disasters in more ways than one — not only are they at risk posed by the natural disaster itself, but also they are exposed to a significant increase in toxic emissions as a result of the disaster. When chemical plants and industries have to shut down operations in the case of a natural disaster or other emergency, toxic substances and pollutants that are still in the system must be burned off. Emergency shutdowns are associated with increased toxic emissions, as was the case with Hurricane Harvey when refineries emitted 4.6 million pounds of pollutants between August 23 and August 30, 2017, exceeding state limits.

This was especially potent in the Harrisburg/Manchester community of Houston in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. Comparisons of soil samples pre- and post-Harvey from households in the neighborhood found that residents were being exposed to a higher amount of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH). PAHs are released when fossil fuels are burned, and are associated with long-term damage to skin, liver, kidneys and eyes.7

Revision starts with recognition

The economic and environmental factors that most contribute to environmental racism may seem built in to our region, but they don’t have to be. As our region continues to expand and evolve, opportunities to rethink where and how we plan our communities will continue to emerge. Recognizing the many manifestations of environmental racism in Greater Houston will help us to make the most of these opportunities and to ensure a healthier, more equitable future for all who call Houston home today and in the future.

Environmental racism is just one part of a larger system of structural racism that undermines our region’s true potential, and knowing the facts is the first step toward taking action. Stay informed on the issues that matter to our region by joining the conversation on social media and getting involved with Understanding Houston.

For a deeper look at environmental racism in Houston, please watch the short video below by Dr. Robert D. Bullard.

References:

1Tessum, C. W., Apte, J. S., Goodkind, A. L., Muller, N. Z., Mullins, K. A., Paolella, D. A., … & Hill, J. D. (2019). Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial–ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(13), 6001-6006.

2Tessum, C. W., Apte, J. S., Goodkind, A. L., Muller, N. Z., Mullins, K. A., Paolella, D. A., … & Hill, J. D. (2019). Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial–ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(13), 6001-6006.

3Union of Concerned Scientists. (2016). Double Jeopardy in Houston. https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2016/10/ucs-double-jeopardy-in-houston-full-report-2016.pdf

4Union of Concerned Scientists. (2016). Double Jeopardy in Houston. https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2016/10/ucs-double-jeopardy-in-houston-full-report-2016.pdf

5Rothstein, R. (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (Reprint ed.). Liveright.

6Horney JA, Casillas GA, Baker E, Stone KW, Kirsch KR, Camargo K, et al. (2018) Comparing residential contamination in a Houston environmental justice neighborhood before and after Hurricane Harvey. PLoS ONE 13(2): e0192660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192660.

7Abdel-Shafy, Hussein & Mansour, Mona. (2015). A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt J Petrol. 25. 107-123. Prince, Ukaogo. (2015). Environmental Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Journal of Natural Sciences Research. 5.