Greater Houston Community Foundation hosted a program on July 20, 2022, to convene experts, researchers and practitioners around the increasingly severe mental health crisis affecting children and adolescents.

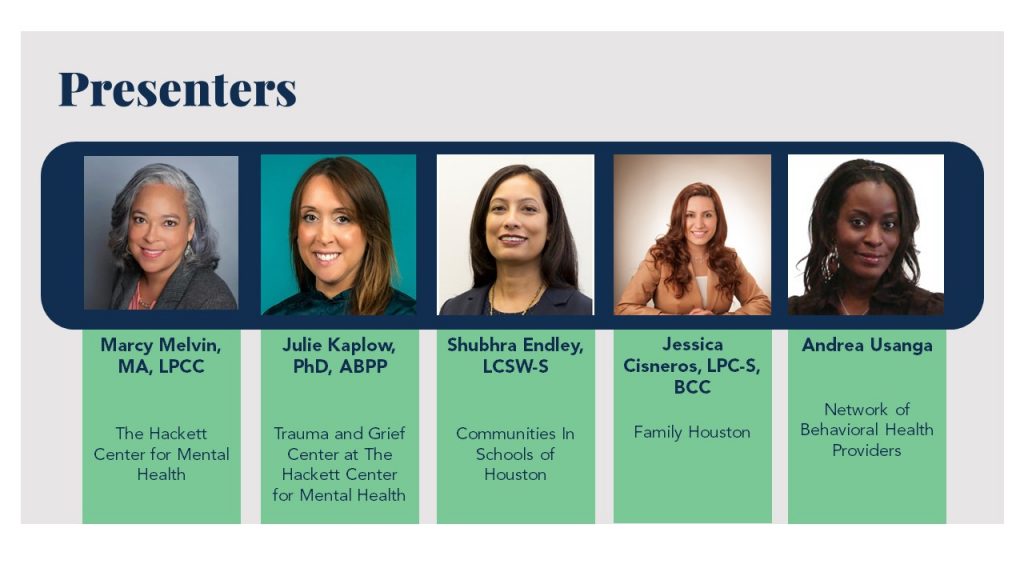

The program began with a brief data presentation from Understanding Houston, to set the stage for the deeper dives from guest speakers that would follow. The convening featured presentations from the following experts:

We explored data and different approaches, which included ways to improve child resilience; treat children who are coping with trauma and grief; identify and serve children in both school and community settings; and the various policy and legislative issues that influence the workforce, funding and efficacy in the mental health space. We have provided a few critical insights below, and we invite you to watch the event here.

Concurrent and consecutive disasters and events have battered our mental health

The past couple of years have been tough on most of us, but research and studies have shown that this time has been especially difficult for children. Not only due to having to navigate an entirely new way of living caused by a pandemic but also because of several successive, traumatic events in recent years. These events, combined with 24/7 news cycles and social media, can contribute to increased feelings of anxiety and unhappiness. However, the data indicates that things weren’t so great even before 2020.

In roughly the last decade from 2009 to 2021, the share of American high-school students who say they feel “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” rose from about a quarter to nearly half, which is the highest level of teenage sadness on record, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But kids are not only struggling with feelings of anxiety and depression brought on by traumatic events. They are also grieving — more than 215,000 children nationally have lost a parent or caregiver who died as a result of COVID-19. Dr. Julie Kaplow, Executive Director of the Trauma and Grief Center at The Hackett Center for Mental Health, calls this the “silent epidemic of childhood trauma and grief.” She emphasizes “silent” because trauma and grief symptoms in children can be disguised which reduces the likelihood of receiving treatment.

Community-based organizations that work to identify and treat mental and behavioral health challenges in children in school settings or otherwise, have been seeing this with their clients for a few years. As Shubhra Endley, Director of Mental Health and Wellness at Communities in Schools of Houston, noted, “We had barely wrapped up our mental health support we were doing in response to [Hurricane] Harvey, and we are now having to deal with housing instability, food instability — because of jobs that got cut during the pandemic — and it’s all impacting the well-being of our students.” Heads around the room nodded in agreement.

Jessica Cisneros, Chief Clinical Officer at Family Houston, noted that it is one thing to identify students in need and offer help, and it is another issue entirely for a family/child to accept support. She notes the historically lower uptake rates among Latinos. Similarly, a survey from Episcopal Health Foundation and Kaiser Family Foundation found that Latinos were the least likely to receive mental health treatment after experiencing negative effects on mental health from Hurricane Harvey compared with Black and white residents.

Aside from the typically lower insured rates among this demographic, cultural norms within the broader Hispanic community can stigmatize mental health treatment. But, that tendency could be reversing. Cisneros shared, “In the Latino community, we have seen a greater focus in reducing stigma by introducing psychotherapists on Spanish-speaking networks,” and she has seen positive results.

There is a clear need for mental and behavioral treatment and therapy. But even if everyone who needs and wants help seeks it out, how available and accessible is treatment?

A local mental and behavioral health provider workforce shortage is exacerbating treatment challenges

Texas ranks last among states in mental health care access according to Mental Health America’s 2022 State of Mental Health report. And, residents in our three-county region have even less access to mental health treatment than the state average. Fort Bend County has the least amount of access to mental health treatment with only one mental health provider for roughly every 1,200 residents.

These numbers cover mental health professionals for all ages, but if we look at the availability of child and adolescent clinical psychologists and psychiatrists, the numbers get worse. According to data from the American Psychological Association, out of the 100,000 U.S. clinical psychologists, only 4% are trained child and adolescent clinicians. Fort Bend, Harris and Montgomery counties all have a severe shortage of practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists.

A Houston Chronicle analysis of staffing at 1,200 school districts in Texas found that many school districts do not meet the recommended ratios for these positions.

- 4 districts met the recommendation for social workers

- 24 districts for counselors

- 25 districts for psychologists

- 398 districts for nursing staff

Andrea Usanga, Executive Director of Network of Behavioral Health Providers, works to increase the provider workforce through education and advocacy. She has been sounding the alarm for over a decade.

In 2009, Usanga testified before the Texas legislature on the mental and behavioral workforce shortage — at the time, about one-third of the counties in the state did not have the designation of partial or total Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). Now, only one county of the 254 does not have a shortage. She urges action, “If we don’t start getting people in [the mental and behavioral health workforce] pipeline to be able to address these issues down the line, we are going to be in even bigger trouble.” Jessica Cisneros shared that Family Houston has also lost a significant number of staff during the pandemic’s peak which has made it harder to treat anyone who seeks help.

We need to do more to prevent challenges from snowballing and giving kids the tools they need to build resilience

Usanga noted in her remarks, “At the exact time we are seeing increases…our available professional supply is going down.” So, how will everyone get the help they need? As Marcy Melvin, Deputy Director of The Hackett Center for Mental Health, implored at the beginning of her talk, we need to “… reimagine how we think about, talk about and define mental health treatment.”

Preventing mental health disorders and building resilience in children to cope with life challenges should be a priority now, Melvin declares. “We are never going to get to the point where we have enough practitioners to meet all of the needs of youth…We can’t stop bad things from happening, but what we can do is build the capacity so that when trauma, hard things happen, we have children and youth who have the capacity to be able to manage and get through those situations.”

Melvin encourages all of us to engage in conversation, lean into community and equip children and youth with the tools they will need to successfully navigate future challenges. The Hackett Center promotes early childhood education as instrumental in that effort. Since a child’s brain is still forming and developing rapidly at that stage, integrating these tools early will build solid brain formation to help children manage stressors effectively. This preventative and resilient approach, particularly when implemented in early years, potentially avoids worsened feelings of hopelessness that can feel insurmountable when we don’t know how to cope.