I’ve been the Pastor of Olivet Baptist Church, located in the Fifth Ward since 2004. Approximately 10 years ago, our church formed a nonprofit, Olevia Community Development Corporation, to take an active role in our community by developing people, property and resources within the Fifth Ward, a consistently under-resourced minority community since its beginning in 1866.

“A Silent Crisis”

In September of 2019, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner launched the first ever Mayor’s Office for Adult Literacy. Director Federico Salas-Isnardi quickly set about employing a two-year study in partnership with the Barbara Bush Houston Literacy Foundation focusing on adult literacy, known as Houston’s Adult Literacy Blueprint, published in 2021.

What the study found was a “silent crisis”: 32% of Harris County adults are functionally illiterate, meaning more than one in every three residents do not have the literacy skills they need “to successfully perform their role on the job, in their family, or in society.” The study’s conclusion: Houston needs to act strategically and proactively to address the pervasive, multifaceted, complex nature of low levels of adult literacy.

Greater Houston’s population of more than 6.2 million is among the most diverse in the country, with a quarter of residents born outside of the U.S. and 145 spoken languages here. In Harris County – there is no racial/ethnic majority – though 44% percent identify as Latino, 19% percent as Black, and 7% as Asian American. Our region’s diversity is a strength — one that brings together different experiences, perspectives, and ideas.

However, we also have challenges. Consider the finding that Black and Latino adults in Harris County are 3 times more likely than white adults to have low literacy skills,1 and that 94% of adult learners in Harris County are individuals from nondominant groups, with the vast majority (greater than 85%) being Black or Latino.2 This report found that the issues of illiteracy are rooted in underlying social conditions which go unnoticed in our collective consciousness.

Why illiteracy matters

The economic disparities in neighborhoods of color in Houston directly relate to overall educational attainment and literacy, by extension. In particular, poverty is closely intertwined with illiteracy. According to one national study, 43% of adults with the lowest literacy skills live in poverty, compared to 4% of those with the highest literacy skills.3

In Fifth Ward, the median income is $38,000 (less than half the state average), 37% live below the poverty line, and 32% of adults have not completed high school. For comparison, about 17% of adults in Harris County have not completed high school and 15% live in poverty.

What the study points out — and what we know from living, working, and ministering in the Fifth Ward — is that children of parents without a high school diploma have a much higher likelihood of also not finishing high school, which establishes a recurring pattern, often spanning multiple generations. With more than one million functionally illiterate adults in Harris County, the implications are dire.

In fact, low literacy rates challenge the well-being and prosperity of families across our region and prevents many adults from reaching their fullest potential in life and the pursuit of the American Dream. When fewer of us do well, that threatens our region’s overall economy and social vitality. The literacy report found that Harris County’s economy could grow by $13 billion if adults with the lowest level of literacy increased their skills just by one level – that translates to a 3.3% increase in GDP. Further, research has shown that adults with low literacy tend to have worse outcomes in health, job opportunities, and economic stability. If low literacy rates in our region continue, we will not have the skilled workforce we need to support tomorrow’s economy, which could negatively impact our region’s growth and prosperity.

Libraries as one tool in the fight

Libraries are champions in the fight against illiteracy as they tend to offer a diverse range of approaches for both children and adults, are generally accessible in neighborhoods, and are free to all. One of the many solutions to tackling adult literacy is to fund more robustly community library programming. This literacy programming should include classes in ESL, workforce development and training, financial literacy, health literacy, and digital literacy. As Edward Melton, Director of the Harris Co. Library System, shared with us recently, “You can’t just build a library and believe people will come. You must have literacy programming dedicated to the needs of the immediate community.”

Recently, we at the Olevia CDC have been working on the development of a library in the Fifth Ward as none exists for the 17,000 people who live in this neighborhood directly adjacent to and northeast of downtown Houston. The City of Houston Library in the Fifth Ward was located next to the Fifth Ward Multi-Service Center, but it received extensive damage from Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and has been closed since.

This void has left the community without a valuable and needed resource for its citizens both young and seasoned for the past six and a half years. That means the following services are not being provided for Fifth Ward residents: programs and events such as story time for children, book clubs, and author talks. Along with missing traditional library services, neighborhood libraries also offer unique resources such as free access to online learning platforms, free tax preparation for seniors, access to free legal aid, health fairs and screenings, food giveaways, and so much more.

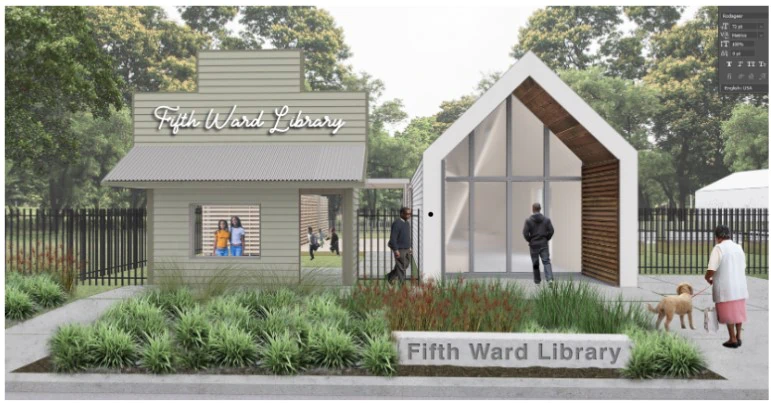

In addition to providing basic services, the Olevia CDC’s library project is primed to be a destination space for the community and the neighborhood as it will utilize a historic building to create an innovative reading space. We partnered with the University of Houston Gerald Hines College of Architecture and the Design Build Master’s Classes to complete a structure that will fit within an existing unused donated structure.

While books and literacy are paramount, we also plan to provide e-books via mobile devices, establish a community garden, host indoor and outdoor performances, an onsite coffee shop, spaces to hold community events, such as weddings, birthday parties, author book signings, Houston sport and entertainer celebrity reading literacy nights, corporate sponsored literacy events and much, much more. We intend for literacy and fun to be interconnected and highlight the true benefits of literacy.

Join the fight

As the Houston community begins to address this silent literacy crisis, it is clear from the Literacy Blueprint report that investing just $2,200 per year in adult education “can raise an adult learner up two grade levels.” By improving adult literacy rates through education and skills training, a greater number of Houston’s most marginalized, including those in the Fifth Ward, will be able to advance economically, support their families, and play a positive role in our society.

There are many ways to join the fight against illiteracy in our region. I encourage you to see how you can get involved in your local library system — such as Harris County’s or Houston’s — to read to children or tutor. You can also join the literacy movement or volunteer in some other capacity. To learn more about our efforts in the Fifth Ward, including our efforts to build a new library, please visit us at Olevia Community Development Corporation.

End Notes

1 Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (2017)

2 Houston-Galveston Area Council (2021)

3 Kirsch, I., et al., Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. (Washington, D.C.: Office of Educational Research and Improvement, U.S. Dept. of Education, 2022) 61.