Domestic violence, also known as domestic abuse or intimate partner violence (IPV), is a pattern of behavior in a relationship used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey published in 2022, half of women and 40% of men experience IPV (i.e., sexual or physical violence, stalking, and psychological aggression by an intimate partner) in their lifetime. These statistics only include individuals who experienced violence in a romantic or sexual relationship. However, domestic violence can occur in many other types of relationships, including between parents and children, grandparents and grandchildren, siblings, current or former spouses, individuals who live together, and both current and former dating partners.

In the U.S., half of women and 40% of men report experiencing intimate partner violence in their lifetime.

Experiencing domestic violence can have long-term impacts on an individual and contribute to prolonged mental and physical health problems. About 34% of women (42 million) and 15% of men (17.2 million) who have experienced IPV also report post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

Beyond the impact on individuals, domestic violence poses a significant public health concern. The National Center for Injury Prevention estimates the cost of intimate partner rape, physical assault, and stalking exceeds $5.8 billion each year—nearly $4.1 billion of which is for direct medical and mental health care services.

It is important to acknowledge that no single study or dataset can fully capture the true prevalence of domestic violence, as it is significantly underreported. The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that less than half of domestic violence cases are actually reported to the police.

The 2021 Harris County Health and Relationship Study found that among domestic violence survivors who sought help, the majority turned to friends or family members. For Houstonians, recognizing the many forms domestic violence can take, who it can affect, and the barriers survivors face when seeking help is essential.

“It is not the victim’s fault – STOP victim blaming. We all need to hold the offender accountable. Change the question from ‘Why doesn’t the victim leave?’ to ‘Why does the offender abuse?”

Amy Smith, Sr. Director of Operations and Communications for Harris County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council

Terminology

The words we use to describe an individual or situation have meaning and can be powerful.

When collecting and analyzing data, using clear and commonly understood language helps ensure consistency and fosters shared understanding across individuals, organizations, and systems. However, no single term can fully capture every individual’s experience or apply universally across all contexts.

In discussions of domestic violence, the term “victim” is commonly used by law enforcement and within legal proceedings. In contrast, many service providers prefer the term “survivor” to emphasize resilience and promote empowerment. Both terms carry significance, depending on the setting and the intent behind their use.

For consistency, Understanding Houston uses data from the Texas Department of Public Safety and aligns with their terminology, which refers to individuals as “victims.” While this reflects the language used in official data collection, it is important to acknowledge the broader context and the diverse ways people may identify their experiences.

Forms of Domestic Violence

Often, when people think about domestic violence, they think in terms of physical assault that results in visible injuries to the victim. However, this is only one type of abuse. There are several other categories of abusive behavior.:

- Control: This can include monitoring phone calls, restricting freedom of choice, and invading someone’s privacy by not allowing them time and space of their own.

- Economic Abuse: This can include controlling the family income, making them turn their paycheck over, causing them to lose a job, or preventing them from taking a job. Being unable to work can make it even more difficult for an individual to leave an abusive relationship, as the batterer keeps them from having the necessary financial resources to support themselves.

- Emotional Abuse & Intimidation: Continuous degradation, intimidation, manipulation, brainwashing, or control of another.

- Isolation: By keeping the victim socially isolated, the batterer keeps the victim from contact with the world. By keeping the victim from seeing who they want to see, doing what they want to do, and controlling how the victim thinks and feels, they are isolating the victim from the resources which may help them leave the relationship.

- Physical Abuse: Which can include hitting, punching, slapping, biting, etc., but can also include strangulation, withholding of bodily needs, injuring or threatening to injure others like children or pets, and hitting, kicking, or throwing inanimate objects during an argument.

- Sexual Abuse: Such as exploiting an individual who is unable to make an informed decision about involvement in sexual activity, laughing or making fun of another’s sexuality or body, and making bodily contact with the victim in any nonconsensual way.

- Verbal Abuse: Coercion, threats, and blame, such as threatening to hurt or kill the victim, their children, a family member, or even themselves, name calling, yelling, screaming, rampaging, or terrorizing.

According to a report from the Texas Council on Family Violence, Texas domestic violence offenders abuse the same victim again in 70% of cases, even after a warning from authorities or after a protective order was issued. Many organizations that work in this area agree that violence almost always escalates over time. This escalation highlights the persistent and increasing dangers victims of domestic violence face and the need for more to be done to ensure their safety.

Rates of Family Violence Increased During COVID and Remain High

Over the past 15 years, the annual rate of reported family violence incidents in Texas has varied but shows an overall upward trend. Since 2018, rates have steadily increased, reaching a 15-year high of 836 incidents per 100,000 residents in 2022. In 2024, 803 incidents were reported per 100,000 residents.

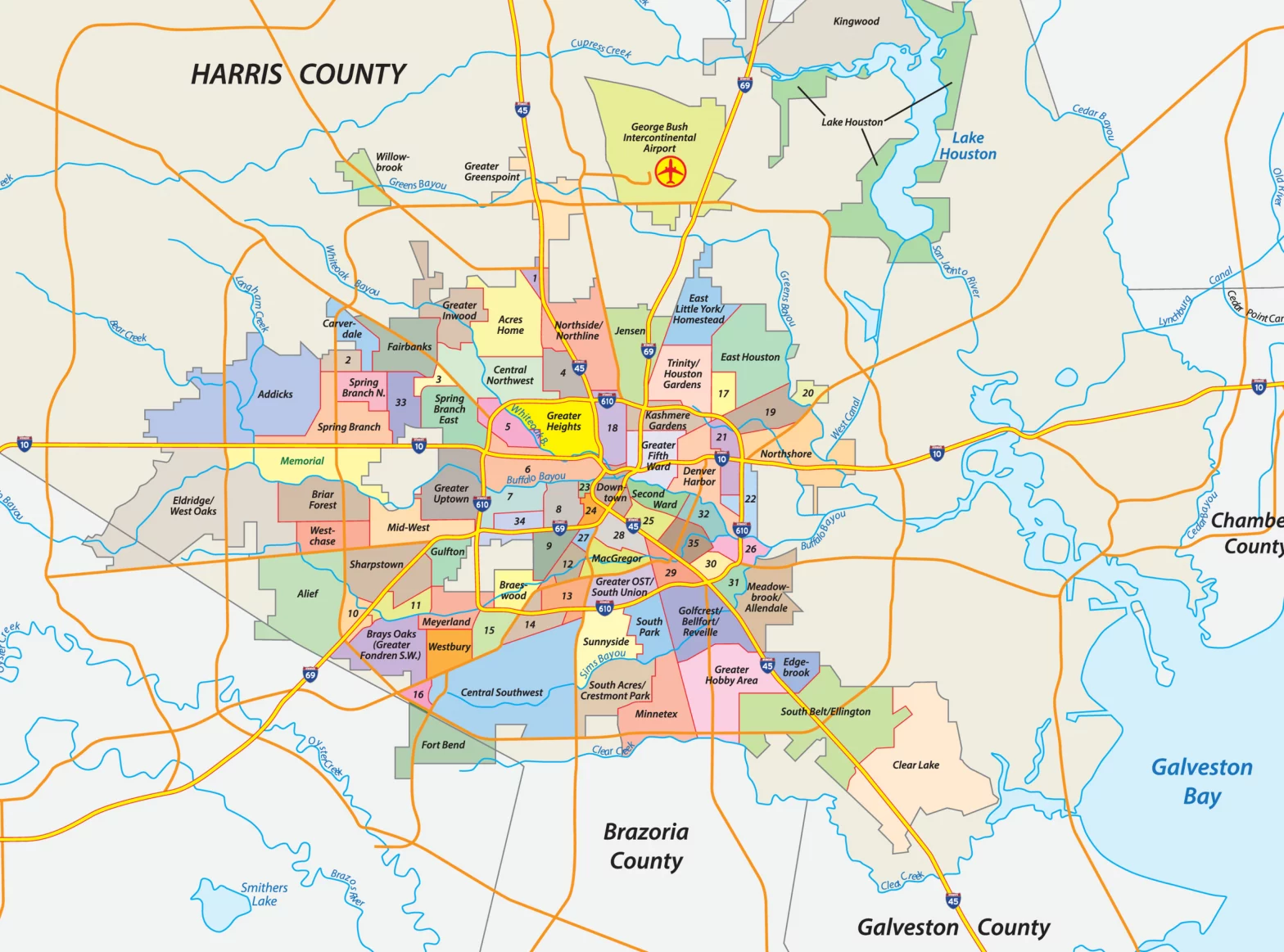

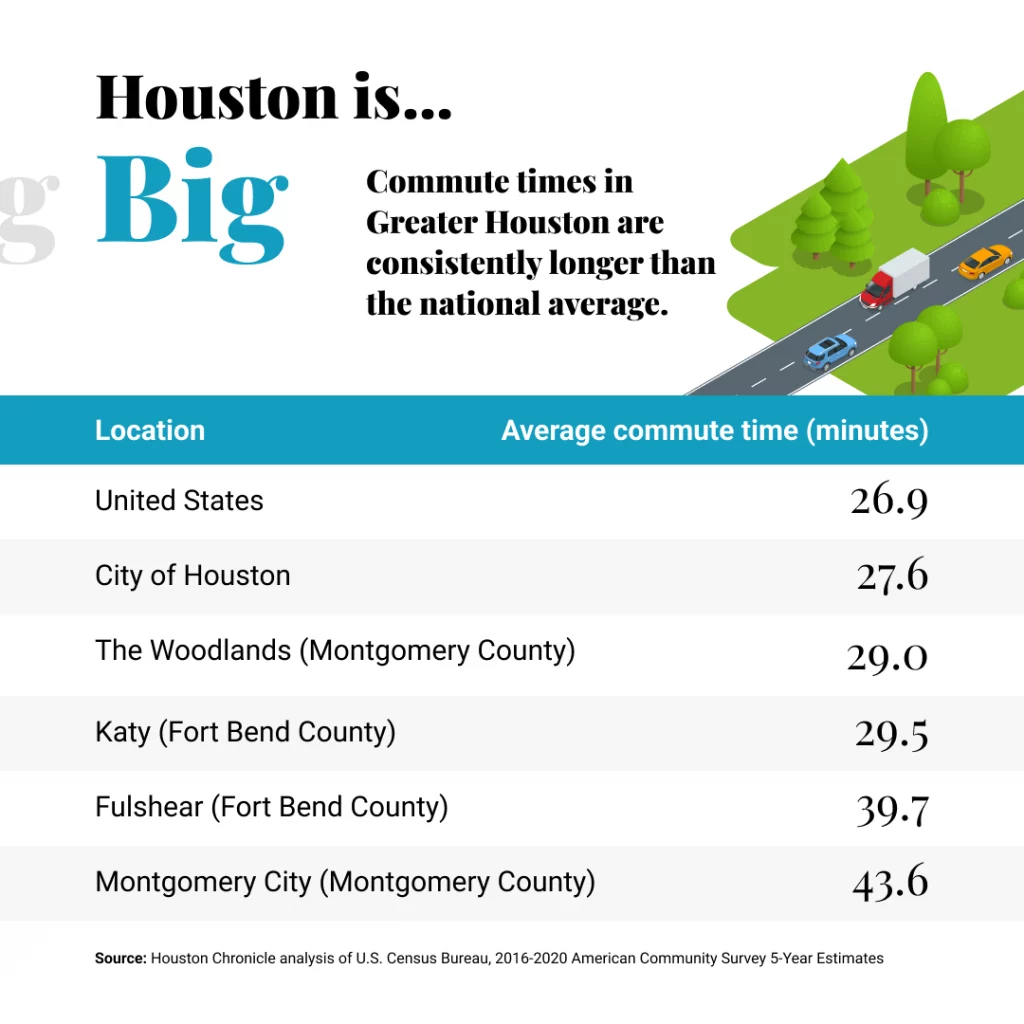

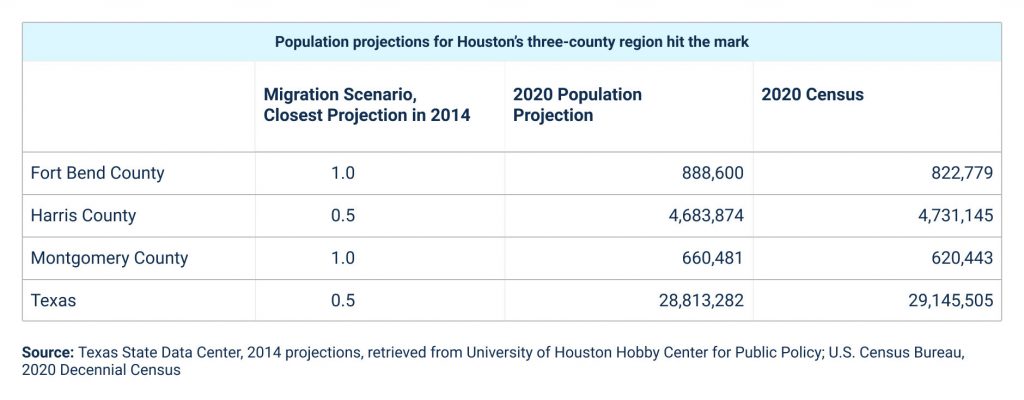

Harris County consistently reports higher family violence rates compared to the state and Fort Bend and Montgomery counties. While rates increased across all areas after 2019, Harris County experienced the sharpest rise—a 28% increase between 2019 and 2020.

Some of the increase may be associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, which introduced additional stressors in households and relationships, potentially contributing to more frequent or severe instances of domestic violence. The 2021 Harris County Health and Relationship Study found that almost 52% of survey participants reported an increase in domestic violence after the COVID-19 pandemic began, and about 6% reported that physical violence began during COVID-19.

However, rates of family violence have remained elevated in the post-pandemic period. During this time, many households in the Houston region have continued to experience economic distress and other challenges that emerged or were intensified during the pandemic.

According to the 2024 Kinder Houston Area Survey, more than twice as many Houston-area residents reported their finances have worsened in the past few years compared to 2020. Additionally, incomes in the region have stagnated. At the same time, the cost of rent has increased; it is estimated that nearly 2 in 5 households are experiencing food insecurity, and the City of Houston now has the highest poverty rate among the top 25 most populous cities in the United States.

Research has shown that economic hardship can increase the rate of domestic violence incidents.1,2 One study found a 30% increased chance of male-perpetrated violence linked to job loss, suggesting that the loss of income can create stress within the household and lead to more time at home, which increases a victim’s exposure to abusive behavior.3

Deaths from Family Violence have Increased Dramatically Since 2017

As we saw, rates of family violence increased across Texas and all three counties in 2020 with the most significant increase occurring in Harris County. However, the number of family violence-related deaths has been steadily increasing across the state since 2017.

Family violence-related deaths in Texas reached a peak of 532 in 2022, the highest in recent history. While deaths have decreased slightly to 465 in 2024, they remain 150% higher than in 2017 (186 deaths). According to the Texas Council on Family Violence, the increases that have occurred after 2017could be due to Hurricane Harvey and/or a higher prevalence of firearms.

- Hurricane Harvey: Studies show that rates of violence can increase in the wake of a natural disaster due to increased mental distress and anger, as well as limited capacity of safe houses due to increased demands from the affected community or damage caused to the building by the disaster.4,5

- Prevalence of Firearms: The number of active licenses to carry in Texas increased from 1.2 million in 2017 to 1.5 million in 2024, a 25% rise. In Texas and the United States overall, guns are the most commonly used weapon in domestic violence-related homicides. In 2024 in Texas, nearly three out of five victims (59%) were killed with a gun.

Research indicates that abusers who own firearms are five times more likely to be involved in partner-related domestic violence deaths. Moreover, domestic violence incidents involving firearms are 12 times more likely to result in fatality than those involving other weapons or bodily force.6,7

“Leaving an abuser is the most dangerous time for a victim of domestic violence. Survivors often stay because of the reality that their abuser will follow through with threats to hurt or kill them, hurt or kill the kids, or harm or kill pets or others.”

Rachna Khare, Director of Community Engagement at Harris County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council

Texas prohibits people convicted of some domestic violence misdemeanors from possessing firearms for five years following their release from confinement or community supervision. However, Texas law does not cover those convicted of violent assaults against a current or former dating partner, known as the “dating partner loophole.” The 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) sought to address this gap at the federal level. However, enforcement of the federal law varies across states due to ambiguities.8 For example, the BSCA does not clearly define what constitutes a “dating relationship” leaving states to define this on their own.9 This creates inconsistencies in how the federal law is interpreted resulting in inconsistent applications across states.

Reported family violence cases are most likely to occur between current dating partners and spouses

Across Texas and the Houston region in 2024, the largest share of family violence incidents reported to the police involved victims who a current dating partner or spouse harmed. While domestic violence directly affects the person being abused, its reach extends far beyond the immediate victim. Children in the household often suffer deep and lasting impacts from exposure to domestic violence. For example, a boy who sees his mother being abused is 10 times more likely to harm his female partner as an adult, and a girl is six times more likely to be sexually abused compared to a girl who grows up in a non-abusive home.

A boy who sees his mother being abused is 10 times more likely to abuse his female partner as an adult.

Because domestic violence perpetrators are often close to their victims, it is difficult for the abused individual to reconcile that they are being harmed. Once they do recognize this harm, victims face several fears and stigmas when reporting the abuse and receiving assistance, which can deter many people from reporting their abuse. Some of the reasons domestic violence is frequently unreported include:

- Fear of the abuser due to threats and ongoing violence

- Custody issues, shared finances or financial instability

- Living arrangements

- Judgment/disbelief/blame from friends, family, or community members

Additionally, the accuracy and type of information collected can vary depending on who is collecting the data and how they interact with the person reporting the incident. If a person does not feel safe or comfortable disclosing specific details—such as how they identify or the nature of their relationship with the abuser—the information provided may be incomplete or inaccurate. In some cases, the available reporting categories may not fully reflect the individual’s identity or relationship. For example, if the relationship does not fit into predefined categories on a reporting form, it may be placed under a broad label such as “Other Family Member.” As a result, certain types of victim-offender relationships may be underrepresented or misclassified in official data.

Nearly two-thirds of reported incidents of family violence had a female victim

In Texas in 2024, there were twice as many family violence incidents reported where women or girls were the victims as incidents where men or boys were the victim. However, the National Domestic Violence Hotline reports that there are likely many more men who do not report or seek help for their abuse due to many barriers. The barriers include men being socialized not to express their feelings or see themselves as victims, pervading beliefs or stereotypes about men being abusers and women being victims, the abuse of men often being treated as less severe, and the belief that there are no resources or support available for male victims.

A disproportionate number of reported family violence incidents are from Black and Hispanic Texans

In 2024, the percentage of reported family violence cases for Black and Hispanic Texans was higher than those demographics’ percentages of the population across the state. Hispanic Texans comprised nearly half (46%) of all reported family violence cases while they made up about 40% of the population. Black Texans made up about 12% of the population but comprised 27% of reported family violence incidents.

However, these numbers are not a perfect representation of family violence as they only represent incidents that are reported to authorities, and specific populations are less likely to report. Depending on an individual’s belief, culture, identity, personal experience, etc. they may have varying levels of comfortability reporting their experience of domestic violence with law enforcement.

In the United States, limited English proficiency is one of the obstacles individuals can face when reporting domestic violence. While all survivors and victims of domestic violence can encounter difficulties when reporting abuse, according to the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence, those with limited English proficiency face additional challenges such as:

- Being stereotyped as uneducated, helpless, or unwilling to learn English or adapt to U.S. culture.

- Not receiving adequate language interpretation or translation services.

- Having an English-speaking abuser mislead or lie to police or first responders by deliberately misrepresenting or falsifying facts claiming that they were assaulted, which can lead to the real victim being wrongfully arrested.

Moreover, across Houston’s immigrant communities, victims face barriers related to cultural taboos, immigration status, cultural mismatches with mainstream agencies, violence from extended family systems, and a lack of knowledge of their legal rights and protective options. As a result, domestic and sexual violence is underreported and underestimated in these communities.

Culture can also impact an individual’s likelihood of seeking assistance when experiencing abuse from someone they have a personal relationship with. The Urban Institute points to research shedding light on underreporting of domestic violence in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community, which shows that deeply internalized patriarchal values could contribute to minimization and underreporting. Cultural values of prioritizing family and community over individuals can lead this population avoiding talking about their domestic violence experiences. Among Asian American and Pacific Islander women, one of the most common barriers to reporting violence is the fear of bringing shame on their family.

Additionally, common factors and considerations exist that may account for underreporting of domestic violence by women of color. They include:

- Cultural norms and/or religious beliefs that restrain the survivor from leaving the abusive relationship or involving outsiders.

- Distrust of law enforcement, criminal justice systems, and social services.

- Lack of service providers that look like survivors or share common experiences.

- Lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate services.

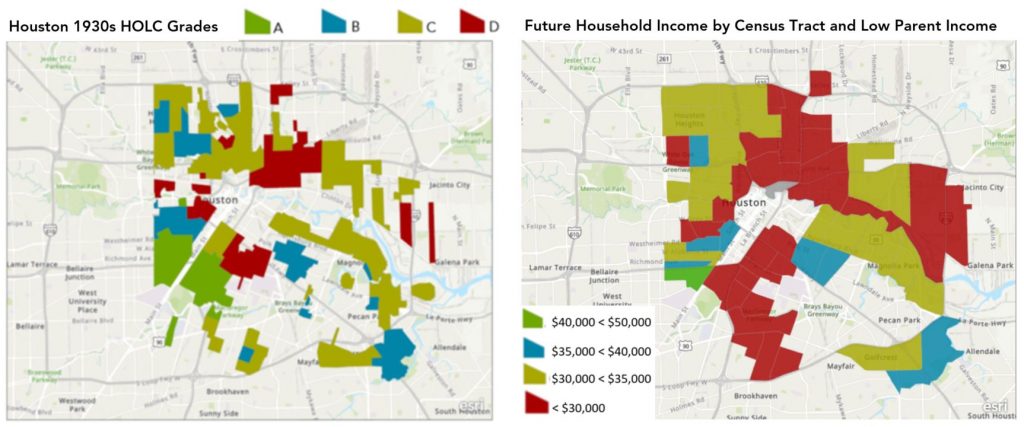

- Lack of trust based on the history of segregation and classism in the United States.

- Fear that these experiences will reflect on, or confirm, the stereotypes placed on their ethnicity.

- Attitudes and stereotypes about the prevalence of domestic violence and sexual assault in communities of color.

- Legal status in the U.S. of the survivor and/or the batterer.

- Oppression, including re-victimization, is intensified at the intersections of race, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability, legal status, age, and socioeconomic status.

“When a survivor leaves, they are taking one of the most difficult and courageous steps imaginable. Our communities can meet that bravery by building a culture where relationships are grounded in respect, safety, and care. These values should define our relationships in moments of calm and in times of crisis.”

Rachna Khare, Director of Community Engagement at Harris County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council

Resources for Survivors

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, several resources are available to assist and answer any questions you may have, including but not limited to.

- National Domestic Violence Hotline: 800-799-7233 or text START to 88788

- Aid to Victims of Domestic Abuse (AVDA): 713-224-9911

- Daya Houston: 713-981-7645

- Fort Bend County Women’s Center: 281-342-4357

- Houston Area Women’s Center: 713-528-2121

- Houston Police Family Violence Unit: 713-308-1100

- Montgomery County Women’s Center: 936-441-7273

- Montrose Center: 713-529-0037

- National Domestic Hotline: 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE)

- The Bridge Over Troubled Waters

Get involved

One of the biggest barriers survivors face to reporting, leaving, or recovering from an abusive relationship is the lack of means to support themselves and/or their children financially or lack of access to cash, bank accounts, or assets. Safe, secure, and affordable housing remains a critical need for survivors to flee. As we work to end domestic violence, housing programs and nonprofit organizations that serve survivors must have access to flexible funds.

Consider donating to, or volunteering with, organizations who provide housing, financial assistance, legal representation, counseling, advocacy, and several other services to domestic violence survivors in our community.

“Getting rental assistance has been one of the most important parts of my life, and it was a turning point. When I first held my keys [to our new home], I cried tears of joy. It was life-saving. The kids were so excited to be able to say they finally had their own place. To this day, my youngest son who was eight years old has the exact date and time memorized for when we first moved into our apartment. If Daya had not helped me and my family with housing, I have no idea how my life would have turned out.”

Anonymous Survivor from Daya Houston

Learn More

If you’d like to learn more, the following organizations provide educational resources.

- AVDA – Get Involved

- Daya – Community Trainings, Prevention & Youth Education

- Harris County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council – DV Training

- Houston Area Women’s Center – What is Domestic Violence?

- love is respect – quizzes (e.g. How would you help someone in an abusive relationship?, Is your relationship healthy?, etc.)

- Montrose Center – Get Involved

- National Network To End Domestic Violence – Frequently Asked Questions

- The City of Houston Mayor’s Office of Human Trafficking and Domestic Violence

References:

1 Schneider, Daniel et al. “Intimate partner violence in the Great Recession.” Demography. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4860387/

2 Medel-Herrero, Alvaro et al. “The impact of the Great Recession on California domestic violence events, and related hospitalizations and emergency service visits.” Preventive Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7315959/

3 Bhalotra, Sonia et al. “Domestic violence: the potential role of job loss and unemployment benefits.” The University of Warwick.https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/cage/manage/publications/bn34.2021.pdf

4 Gearhart, Sara et al. “The Impact of Natural Disasters on Domestic Violence: An Analysis of Reports of Simple Assault in Florida (1999-2007).” Violence and Gender. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/vio.2017.0077

5 First, Jennifer et al. “Intimate Partner Violence and Disasters: A Framework for Empowering Women Experiencing Violence in Disaster Settings.” Journal of Women and Social Work. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0886109917706338

6 Campbell, Jacquelyn et al. “Risk Factors for Femicide in Abusive Relationships: Results From a Multisite Case Control Study.” American Journal of Public Health. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1089

7 Saltzman, Linda et al. “Weapon Involvement and Injury Outcomes in Family and Intimate Assaults.” Journal of American Medical Association. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/397728

8 Pulliam R, Bauman K, Smith J, Rice K, Harper GW. Closing the Gap: The Need to Eliminate Loopholes in Legislation at the Intersection of Gun Violence and Intimate Partner Violence. Undergrad J Public Health Univ Mich. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12360288/

9Robert Leider. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act: Doctrinal and Policy Problems. https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg/vol49/iss2/2/